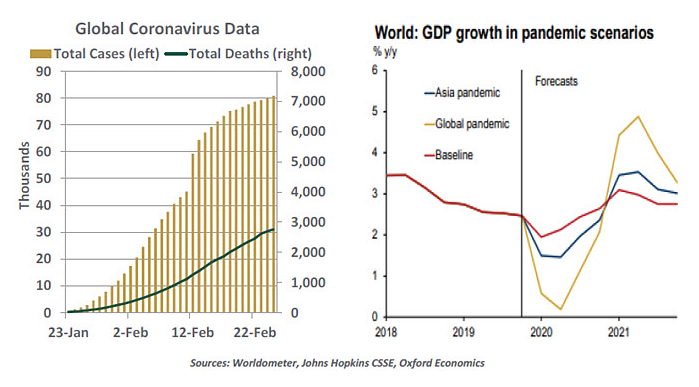

We’ve been closely watching developments related to COVID-19 for the past several weeks. While we have hesitated to make significant changes to our outlook until evidence is clearer, we now expect the economic damage done by the outbreak will be more significant than initially thought.

Here is the basis for that conclusion:

a. Overall growth in Chinese patient counts is slowing, but new outbreaks outside of Wuhan (the origin of the virus) may slow the relaxation of quarantines in China. Evidence from recent trends in Chinese traffic, power usage, travel and property sales suggests the recovery of production has barely started. Tens of millions of Chinese workers are far from their jobs. It could be a long time before China is back to full capacity.

As tempted as Chinese officials must be to get the engines running again, they are also wary of inviting a public health relapse. The regime has been on the receiving end of a certain measure of public apprehension over its handling of the crisis, and will be very anxious to restore a sense of control.

b. Patient counts outside of China are small, but have grown suddenly in places like Italy, Japan and South Korea. Preventative measures in those countries will further interrupt global economic activity; all three are at growing risk of recession. Public health officials are acting pre-emptively, and will relax restrictions cautiously. This is as it should be. But the best medical strategy is also the most disruptive to the economy.

We should note that controlling the outbreak is both a medical and a psychological exercise. Unless and until there is a broad sense that the crisis has passed, consumer and business behavior will remain subdued.

c. Intelligence from a broad range of industries reflects discomfort emanating from China. Just-in-time processes, which have led to heavy reliance on Chinese suppliers, have impaired production for many manufacturers (see following article). A colleague observed that you can’t complete a product if you are missing even a few parts; inventories of parts have been worked down dramatically over recent decades to save money, so there isn’t a backlog to draw from.

Suppliers of commodities to China have had contracts cancelled. Shipping and logistics companies report steep drops in freight traffic from Asia. Interestingly, readings on the U.S. service sector have dipped, with COVID-19 cited as a proximate cause. Reaction has been much broader than initially anticipated.

d. Companies inside and outside of China will suffer business interruption of varying degrees. Some of these firms do not carry the highest credit ratings, and may be at risk of default if normal levels of activity are not restored soon. In China, small business loans are a focal point; in the U.S., the pool of BBB-rated companies bears watching.

e. The direct channel of contagion to the U.S. economy is the financial markets, which are faltering as of this writing. To be fair, equities have proven impressively resilient in the face of various challenges during the past 11 years. But global prospects are being downgraded, and risks remain on the downside. That combination may prompt a more sustained “risk-off” posture from investors. And if the correction is sustained, cost containment could follow.

As the U.S. Federal Reserve prepares for its next meeting in three weeks, troubling anecdotes will likely be prominent in regional economic summaries (the “Beige Book”). The staff will probably come to the same conclusion that we have: we are not looking at a temporary interruption from which there will be a “V-shaped” recovery. Even if China goes into overdrive after production resumes, bottlenecks elsewhere will constrain the recuperation.