The battle against inflation is far from over, but markets can’t be blamed for rushing to judgment after an unequivocally positive consumer price index report Tuesday.

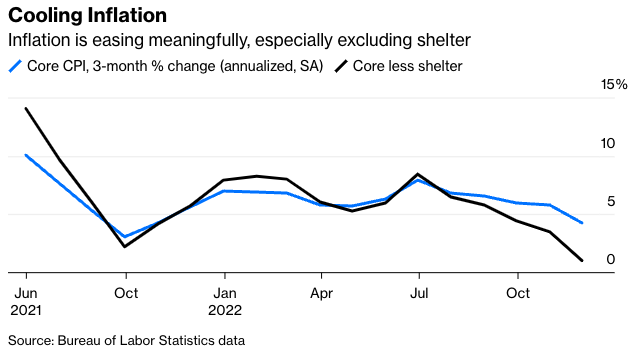

The numbers showed that core prices—excluding volatile food and energy—rose just 0.2% in November from the previous month. Stripping out the contentious shelter component of the index, core prices actually fell 0.1% on the month. Using a three-month annualized rate to smooth out the month-to-month volatility, the core index excluding shelter suggests an underlying rate of core inflation of just 1%—below the Federal Reserve’s target.

True to form, the S&P 500 Index jumped 2.5% on the news and the yield on 10-year Treasuries fell 16 basis points. In the past, such moves would have been viewed as “getting ahead of ourselves,” but this one is different.

Consider the policy backdrop. The CPI carries a special measure of weight this month, of course, because it comes on the eve of the next Fed monetary policy decision. The Fed’s rate-setting committee is still likely to raise interest rates by 50 basis points on Wednesday, but there can be little doubt that the numbers will embolden doves who think that the balance of risks is tipping toward recession over inflation. There should be some meaningful debate among committee members about making the next rate increase the Fed’s last, and markets will be waiting with bated breath for signs of how receptive Chair Jerome Powell is to that argument.

So what does that mean for the medium term? For starters, it means price-earnings multiples can continue to drift higher. Higher risk-free rates have been the dominant driver in the compression of forward P/E ratios since January, with multiples plummeting from about 21.6 times in January to a low of 15.2 times in late September. At the current 17.8 times, they could track bond prices higher if inflation keeps moving in this direction.

Equally significant, the development bolsters the argument for a soft landing in the economy. A sizable chorus of economists thinks a recession may already be baked in for 2023 thanks to the famous “long and variable lags” of monetary policy; the damage has already been done, many might say. But a quick resolution to the inflation problem at least increases the odds of avoiding that outcome and opens the door to an upside surprise. S&P 500 strategists are already bracing for meager 3% earnings-per-share growth in 2023. A very modest uptick in EPS expectations (say, 5% growth in 2023 instead of 3%), combined with a reasonable 19 times multiple, gets you back to around 4,400 on the index, another 8% upside from current levels.

As always, there’s risk in overextrapolating from what now stand as just two consecutive encouraging CPI reports. Fed policymakers have been burned by volatile inflation data already, and they’ve been conditioned to be more cautious going forward. “Nobody likes to get headfaked, and the way for Powell and his colleagues to get headfaked is to overreact to a couple of encouraging releases,” David Wilcox, director of U.S. economic research at Bloomberg Economics, told me Tuesday on a Twitter Spaces broadcast.

At his Brookings Institution speech last month, Powell himself laid out four pillars for thinking about the inflation outlook, implying that he won’t consider lower interest rates until he finds ample comfort in each of them. Here’s where the Powell framework stands after Tuesday’s report:

• Growth running far enough below long-run trend to reduce inflation (check).

• Clear signs of housing and rent disinflation, at least in forward-looking indicators of market rents (check).

• Cooling core goods inflation and healing supply chains (emphatic check: core goods prices actually fell outright for the second consecutive month.)

• Cooling core services less shelter, and a more sustainable pace of wage growth (still not there: core services excluding shelter rose just 0.2% in the most recent report, but the last three months’ data suggest an annualized rate of around 6%).

More to that final point, trend wage growth still looks to be around 5%, a thorn in Powell’s side that he fears will make services inflation harder to tame in the medium term. Clearly, the wage debate has its detractors who note that the current bout of inflation didn’t start with the labor market and think that the relationship between tight labor markets and inflation is antiquated. That could be, but the Fed is going to hold on to that line of thinking until the hard inflation data prove it unequivocally wrong. Yet while the Fed waits on clear and compelling evidence that inflation is back in its cage, market participants have no such luxury. And for once, you can’t really blame them.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.