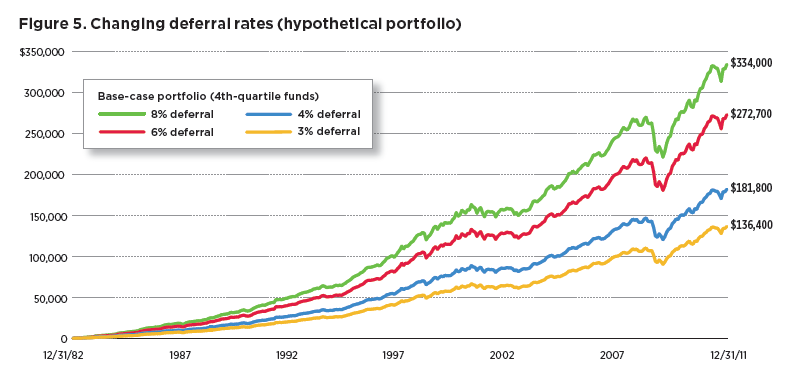

It should come as no surprise that if one saves and invests more, then one might be more likely to accumulate greater wealth. But, as Figure 5 suggests, the size of the difference in terminal wealth can be dramatic. As we dial up the individual's contribution from 3% of income to 4%, 6%, and 8%, the final balance after 29 years jumps from $136,000 to $181,000, $272,000, and $334,000, respectively. Interestingly, even a 4% deferral - which represents a 1% increase that does not take advantage of the plan's full matching contribution - would have had a wealth accumulation impact 30% larger than the crystal ball fund selection strategy, nearly 100% larger than the growth allocation strategy, and approximately 2,000% larger than rebalancing. Putting deferral rate changes in these terms, the performance of underlying funds and rebalancing, in particular, appear to become far less meaningful when compared with the impact of higher deferral rates.

Implications For Plan Design And Participant Education

Readers may observe that the remarkable difference in wealth afforded through higher deferral rates affects the individual's portfolio only, and does not concern the overall performance of the plan. While this is true in certain respects - as we have modeled the effects of different factors on the wealth accumulation potential of an individual rather than an entire plan base - it is more important to recognize that our analysis suggests a hierarchy of priorities for plan sponsor activity.

How should plan sponsors and their advisors spend their time? Should they focus on fund selection, asset allocation, rebalancing, or increasing deferral rates? After decades of experience, we now know that for the vast majority of participants, inertia rules the day.

Against this behavioral bias, our data suggest that focusing on helping eligible employees enroll and/or increase their deferrals into their DC plan is a good way to help boost wealth accumulation potential. For this reason, we feel that services such as auto-enrollment and auto-deferral increases are two critical best practices that plan sponsors should consider implementing.

Data are historical and based on hypothetical investment scenarios outlined in Section 4. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. More recent returns may be higher or lower than those shown. Investment return and principal value will fluctuate, and shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost.

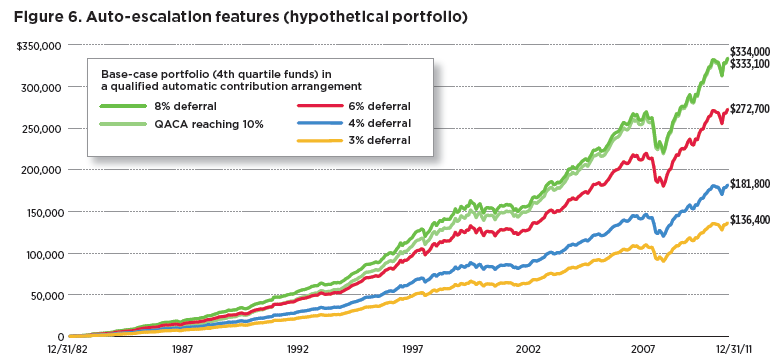

Data are historical. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. More recent returns may be higher or lower than those shown. Investment return and principal value will fluctuate, and shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost.

Importantly, these features do not carry high fiduciary risk. Compared with the practice of offering employee education and/or advisory services in an attempt to migrate participants toward more aggressive asset mixes - activities that carry higher fiduciary risk and may require expensive or complicated communication initiatives whose potential is uncertain - a focus on higher deferral rates has a low total cost to the plan sponsor and enormous upside potential for participants.

While plan sponsors may recognize the need to increase savings, 74.3% of plans utilize automatic enrollment at a deferral rate of 3% or less. For many plan sponsors, this is an attempt to increase participation in a way that will not dramatically impact the participant's wallet. By contrast, 62.1% do not have an automatic escalation provision.2

The Pension Protection Act of 2006 introduced a Safe Harbor provision that offers a solution to this problem. As Figure 6 shows, a qualified automatic contribution arrangement (QACA) that increases an individual participant's deferral rates from 3% to 10% by one percentage point annually - and then maintains a 10% deferral rate thereafter - would have roughly the same impact as an 8% deferral rate over the 29-year time frame employed in our study. Clearly, auto-escalation features can play a vital role in helping secure substantially higher savings for plan participants, particularly the majority of savers who have historically tended to participate passively in their plans.

Conclusion

For many years, fund performance has taken center stage in the discussion of DC plan effectiveness and how to improve it. With the present study, we hope to shift the emphasis of that discussion to deferral rates - and the ways in which plan design and employee education can be leveraged to raise deferral rates for eligible participants. The foregoing analysis is not intended to suggest that underlying fund performance is not important. Rather, it is intended to show that a number of variables are at work in determining plan effectiveness.