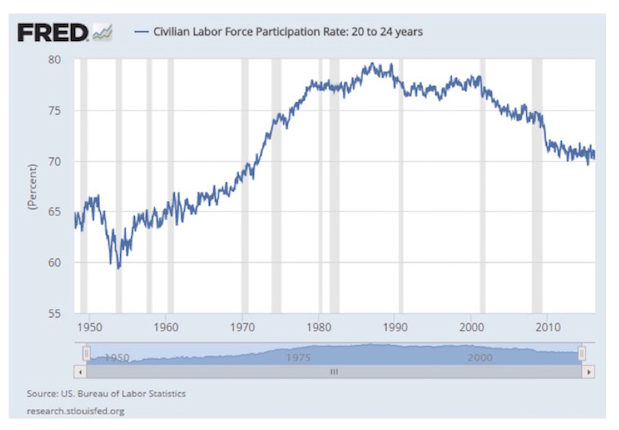

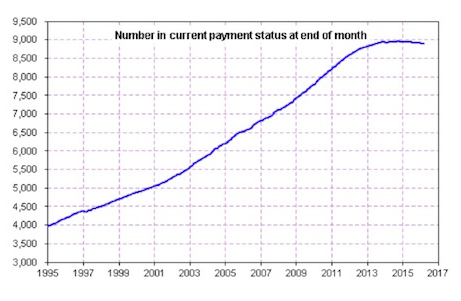

The next two charts are interesting. The first originates from the Atlanta Fed and shows the reasons why different age groups are not participating in the labor force. What I find interesting is the number of disabled people at younger ages. In the 46–50-year-old cohort, we see that 10–15% are classified as disabled. The number of people getting disability benefits has skyrocketed over the past 15 years, and especially since the Great Recession, although growth in the number on disability has flatlined in the last few years as applications have fallen off with the improvement in the economy.

Notice, too, the large numbers of people in younger cohorts who are out of the labor force because they are taking care of family. And while most of these individual situations are probably very necessary, they do have an effect on overall economic growth.

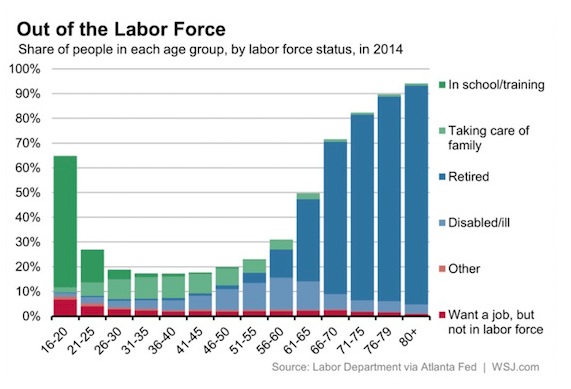

The following chart from the Social Security Administration shows the actual numbers of people with disability insurance claims. But what the chart really tells us is that these 9 million people are not available for the workforce. And while they all have their personal reasons for being on disability, their low incomes and basic lack of productivity do not contribute to the growth of the economy.

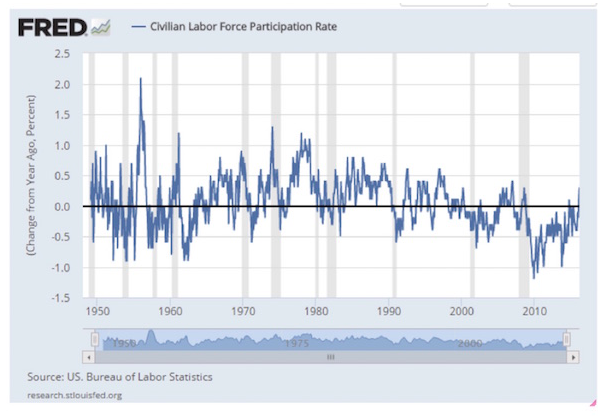

One last chart, and then we’ll try to wrap up. This one shows the percentage change in the labor force participation rate year-over-year. What we see is that the rate has generally declined since the late ’70s, except for a few years of very modest growth within the last 16 years. Returning to our basic equation, if the number of people working is not increasing, then (notwithstanding overall growth of the population) it is very difficult to eke out positive GDP numbers.

The trends we have looked at are not likely to change much, which means we are facing a long period of restrained GDP growth throughout the developed world.

This demographic cast iron lid on growth helps explain why the Federal Reserve, ECB, and other central banks seem so powerless. Can they create more workers? Not really. They can make a few adjustments that help a little – confident consumers are more likely to have children, but it takes time to grow the children into workers.

What Fed policy is clearly not doing is to encourage businesses to invest in growth. Business loan availability is still a problem in many sectors. Increasingly, businesses that can borrow do so not in order to build new facilities but rather to buy back their own stock or to pay dividends. The numbers of mergers and acquisitions, and their value, has been rising since the advent of super-low interest rates. It is cheaper to buy your competitor than to compete. Buyouts help shareholders but not workers, as they typically entail a consolidation of company workforces and a reduction in the number of “duplicated” workers. While this culling may be good for the individual businesses, it is not so good for the overall economy. It circumvents Joseph Schumpeter’s law of creative destruction.

In summary, unless something happens to boost worker productivity dramatically, we’re facing lower world GDP growth for a very long time. Could we act to change that? Yes, but as I look at the political scene today, I wonder where the impetus for change is going to come from, absent a serious crisis. And when we’re embroiled in a crisis, we’re already in a hole, trying to dig out, which means we have even further to go to achieve robust growth – assuming we can even do the right things in a crisis. Given what we did in the last crisis, it is not clear that we still have that capacity.

For investors, this is reality: developed-world economies are going to grow slower. And companies, whose revenue is essentially a function of the growth of the overall economy, are going to grow slower, too, in general.

Dallas, Houston, Abu Dhabi, Raleigh, and SIC

This week I will speak in Dallas for the seventh annual Inside Retirement conference, May 5–6. They have a great lineup of speakers, but I am most excited about getting to hear and maybe even talk with my personal writing hero, Peggy Noonan.

Then on May 10 I fly down to Houston to speak at the S&P Dow Jones Art of Indexing conference. The conference is for financial advisors and brokers who are trying to understand how to manage risk while maximizing returns in the current environment.

I will be in Abu Dhabi the third week of May and then come home and almost immediately go to Raleigh, North Carolina, to speak at the Investment Institute’s Spring 2016 Event. I’m looking forward to hearing John Burbank and Mark Yusko (who will also be at my own conference the same week) and then to being on a panel with them.

Afterward, I make a mad dash for the airport, arrive back in the Dallas late Monday night, and make final preparations for my Strategic Investment Conference, where upwards of 700 of my closest friends will gather to discuss all things macroeconomic and geopolitical. It is going to be a great week! If you won’t be going to the conference, you can have the next best thing: recordings of the speakers, delivered just a few days after SIC 2016 ends. You can order your set here. I should note the price will go up after the conference. A lot. So just jump on this offer now.

And since I’m promoting Mauldin Economics, you will shortly see (if you haven’t already) a promotion for a new investment newsletter service called the Macro Growth and Income Alert. Patrick Watson, Mauldin Economics Senior Economic Analyst, will coauthor the new letter, along with Senior Equity Analyst Robert Ross.

I first hired Patrick in the late ’80s to help me write. He had left the military and had just graduated from grad school at Rice University (which, I must confess, moved his résumé to the top of the list), but what made me take on a budding young writer was the solid portfolio of excellent writing on a variety of topics that he sent me. Not quite sure how long we worked together that time around, but maybe 10 years? He eventually moved to Austin, where he went to work for my partner and then moved on to several other publishing companies. We stayed in close touch and compared notes over the years, and a few years ago I finally persuaded him to come back to work for me.

Patrick has read everything I have written for the last 25 years (and has edited a lot of it), and he feeds me a continuous stream of research. As a result, we long ago became thinking and working partners whose ideas and styles are completely in tune.

I had to persuade my Mauldin Economics partners to pony up to afford Patrick, but I promised I would make up the difference if they didn’t think he was worth it. They now wish they could figure out how to clone him a few times. I do, too.

I think Patrick and Robert’s Macro Growth and Income Alert is going to be very successful and their readers very satisfied. As usual with a new service, we are deeply discounting the initial price, so rather than waiting to subscribe, you might want to try it out. There is a 90-day guarantee for a full and courteous refund, so that you can enjoy a risk-free trial. You can learn more right here. You may also want to follow Patrick’s always-entertaining Twitter feed @PatrickW.

I am going to hit the send button now without adding further personal comments, as I have a few things begging to be done. And it is turning into a beautiful day that I want to enjoy here in Dallas. I hope your day is just as fine, and do have a great week!

Your planning to participate in the labor market a long time analyst,

John Mauldin

John Mauldin is editor of Mauldin Economics' Outside The Box.

This article was originally published at Mauldin Economics.

Delta Force

May 2, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment