Last month, the Federal Reserve kicked off a campaign to increase interest rates to bring down the highest inflation the U.S. has experienced since the 1980s. Critics contend the Fed still isn’t doing enough, and the central bank seems to agree. Several high-ranking Fed officials, including Chair Jerome Powell, have said in recent days that interest rates may need to rise faster, and possibly higher, than initially planned.

The bond market has been banking on it for months. The yield on two-year Treasuries usually hugs the federal funds rate, the overnight bank lending rate the Fed uses to move short-term interest rates. But the two-year yield has shot up to 2.3% from near zero last fall, racing 2 percentage points ahead of the fed funds rate in anticipation that the Fed will have to raise rates by at least that much — and soon.

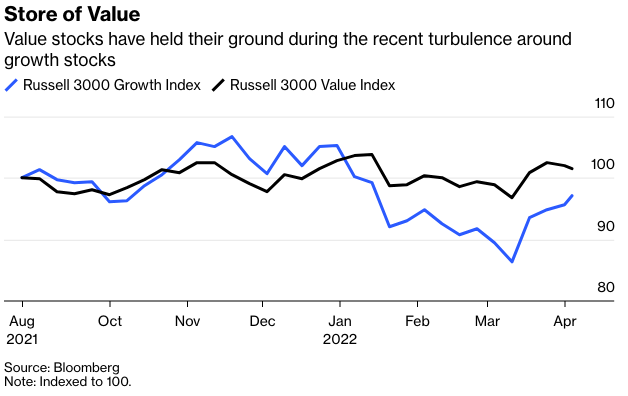

Some investors say the impact of those interest rate moves are already visible in the stock market. Since two-year yields began climbing last fall, growth stocks, as represented by the Russell 3000 Growth Index, are down 3%, while the counterpart Russell value index is up 2%. That’s no coincidence, they contend, because rising rates hurt growth more than value.

The theory is that stock prices reflect the present value of future earnings. The rate investors use to “discount” future earnings to the present is based in part on prevailing interest rates. The way the math works, the higher the interest rate, the less future earnings are worth, all else being equal. In simplest terms, $100 of earnings divided by 1% is $10,000, whereas the same $100 divided by 2% is only half as much. Given that growth companies are expected to generate more of their earnings in the future, they presumably have more to lose from rising rates.

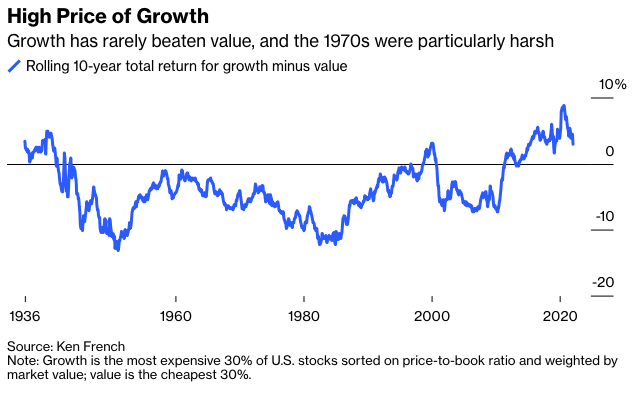

The perception that rising rates batter growth stocks has been seared in some investors’ minds since the 1970s. From 1972 to 1981, the Fed raised the fed funds rate to nearly 20% from 3%, lifting interest rates with it. At the same time, growth stocks, as measured by the most expensive 30% of U.S. stocks sorted on price-to-book ratio and weighted by market value, lagged value stocks, the cheapest 30%, by a staggering 10% a year, including dividends. That’s among the highest underperformance for growth relative to value in any 10-year period before or since going back to the 1920s.

But were the 1970s typical of other rate-hiking campaigns? In a recent column, I looked at how the stock market fared during the Fed’s 13 rate-hiking campaigns since the 1950s. Contrary to fears that rising interest rates are bad for stocks, I found that the market rose during all but two rate-hiking campaigns, including the late 1970s and early 1980s.

This time I looked at how growth and value performed during the same 13 rate-hiking campaigns. What I found was a tale of two periods. From the 1950s to the 1980s, value won in seven of nine rate-hiking campaigns, by huge margins most of the time. And during the two occasions when growth won, it barely squeaked by value. Looking at those numbers at the end of the 1980s, it would have been tempting to conclude that rising rates give value the edge.

Then everything changed. Growth has won in three of four rate-hiking campaigns since the 1990s, undermining the idea that rising rates are harder on growth stocks. If anything, growth should have been even more vulnerable to rising rates in recent decades. Beginning with the internet boom in the 1990s, growth investing has been dominated by companies promising mind-boggling earnings growth, from Microsoft Corp. in the ’90s to Tesla Inc. today. If higher interest rates cause investors to write down the value of future earnings, then value should have had an even easier time outpacing growth during recent rate-hiking campaigns than it did previously.