Since World War II, the U.S. stock market has always gained in the year after midterm elections, but there are plenty of reasons to think the streak is about to end.

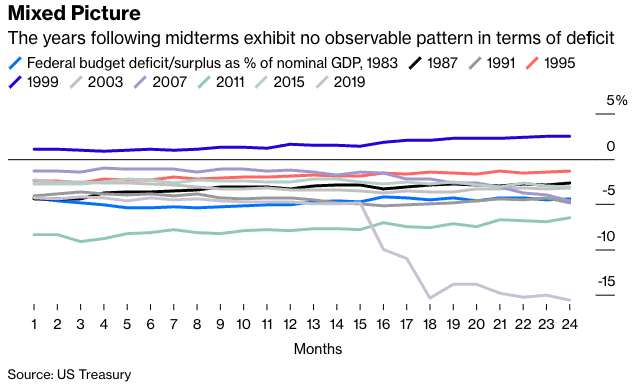

Consider the flimsy attempts to explain what may otherwise be a coincidence. One leading explanation is that midterm elections generally lead investors to anticipate the arrival of a new legislature with a potentially stimulative fiscal agenda. But that’s true only occasionally, and it almost certainly won’t be the case this time around. Here are fiscal deficits as a percent of nominal gross domestic product in the two years after midterms; there clearly isn’t much of a pattern:

Incomplete counts from Tuesday’s balloting show that Republicans are edging toward control of the House, although they probably won’t register anything near the red wave some had predicted. With inflation still hovering around a 40-year high, the divided government that’s likely to result from Tuesday’s voting will probably face gridlock, and President Joe Biden will find little consensus for any spending that could be perceived as juicing the economy. Even if such legislation were to make it to Biden’s desk in the next couple years, central bankers would quickly act to counter anything with a whiff of fiscal stimulus.

Historically, the most convincing explanation for the post-midterm stock rally phenomenon is much simpler: Equities tend to post disappointing results in the years before midterms—perhaps because of overdone anxiety about the policy implications—and returns tend to bounce back afterward. It’s essentially mean reversion; in fact, the average return for stocks in the two years before and after midterms is entirely normal and unremarkable. This time around, stocks have certainly slumped ahead of the vote, but for fundamental reasons that have nothing to do with politics.

From a policy standpoint, it’s hard to see how these elections will provide a strong fundamental boost to stocks, and they could end up making matters worse at the margin. One risk is that divided government will set the stage for another so-called debt ceiling standoff like the one in 2011, when Standard & Poor’s ended up cutting the U.S. credit rating to AA+ from AAA. The debt limit must be raised next year to accommodate preexisting spending plans, and Republicans could conceivably use that as leverage to extract concessions from their Democratic colleagues. As Anna Wong, Bloomberg Economics’ chief U.S. economist, has pointed out, a reprise of the type brinkmanship from a decade ago could lead to more financial market volatility and push borrowing costs higher, potentially leading to a recession that is deeper than otherwise expected.

So what should markets expect going forward? The answer mostly boils down to corporate earnings and the Federal Reserve, not Congress. The lion’s share of the selloff in stocks this year reflects the declining price-earnings multiples that investors are willing to pay in an environment of higher interest rates. It’s conceivable that peak interest rates are already priced into the market, but with the Fed committed to bringing inflation to heel, it’s unlikely that they will drop precipitously in the next 12 months. In that sense, the fate of stocks still depends almost entirely on the continued buoyancy of corporate earnings. If the U.S. tumbles into a recession, as economists increasingly expect, the post-World War II streak is as good as over, and it was probably a spurious phenomenon anyway.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.