European banks are vital to economic recovery in Europe; low and negative interest policies in Europe not only hurt banks, but may be counterproductive to boosting the economy. Banks in Europe are more structurally important to the economy for a number of historical and structural reasons. The European Central Bank’s (ECB) expansion of money supply and low to negative interest rate policy were designed to aid the economy. But the negative impact on banks has limited lending, therefore countering this state policy. Banks have belatedly begun to increase lending. Stock prices for European banks tend to rise with increases of lending, though historically it takes some time (approximately a year) for stock prices to begin to follow actual loans.

WHY DO RATES MATTER?

We have taken our title from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which Polonius, a pompous and self-serving advisor to the king, provides a series of life lessons to his son. “Neither a borrower nor lender be” is one of the most famous. Of course, Polonius is informing his son that borrowing and lending put the parties at odds with each other, working against both parties intentions. The ECB appears to have failed to heed this lesson. It has engaged in a number of measures to spur the economy by encouraging borrowing and spending. In particular, interest rates have been reduced to zero, and in an increasing number of cases have been negative. The ECB has also been purchasing bonds from banks at a record rate through its quantitative easing (QE) program. The idea behind these policies is that by reducing interest rates, corporations will increase their borrowing for investment and consumers will use low rates to borrow and spend.

However, the low rates have failed to do much to stimulate the economy, and may even be worsening the malaise. One reason may be the negative impact these policies have on banks. Low interest rates dampen bank profits; the bank simply doesn’t make much money on the loans. This can result in a tightening of lending standards, as banks do not feel they can be adequately rewarded for taking on additional risk. Low interest rates also may lead savers to not use banks; they may withdraw their principal from the banks, as they don’t earn enough on their savings to meet their spending needs. Low rates encourage savers to look elsewhere, maybe even out of the country, seeking higher rates. By depriving banks of this source of funds, the ECB is partially negating its own policy.

In today’s environment, Polonius’s words can be seen as a warning to the financial industry. Go ahead, try to borrow and lend, but you aren’t going to make any money at it. But it’s also a warning to the ECB: be careful of the unintended consequences of your actions.

WHY DO BANKS MATTER?

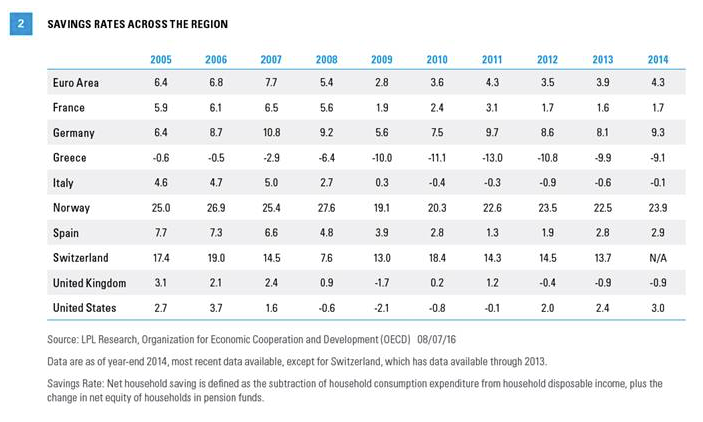

Banks and bank lending are much more important to the European economy than they are in the U.S. In Europe, approximately 80% of all corporate debt is in the form of a bank loan, with only 20% structured as a bond. In the U.S., those figures are approximately reversed. The differences in the regions are even more striking when looking at sources of credit as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) [Figure 1]. The U.S., the Eurozone, and the U.K. all have very similar private sector debt-to-GDP ratios. However, the European nations, including the U.K., which is counted differently as it does not use the euro, are more reliant on banks to fund the economy. This tendency is somewhat surprising for the U.K., which typically follows the more dynamic Anglo-Saxon model of capitalism, relying on the capital markets—the issuance of stocks and bonds, and the trading of loans through the securitization of debt—to finance corporate activity.

When we look down to the capital structure, to high-yield bond issuance, levered loans, and securitization of debt, the difference between Europe and the U.S. grows even starker. By some estimates, European issuance of high-yield debt is only 35% of that of the U.S. when adjusted for GDP. The securitization market is only 17% of that of the U.S., adjusted the same way. Relative to the U.S., not only do European banks create a disproportionate amount of the credit, they tend to keep the loans on their books. This does not allow banks to diversify these risks. It also may mean that if a bank is overleveraged, or has too much bad debt, it may reduce lending to good creditors, which hinders economic growth.

Both the causes and effects of the dominance of traditional banking, rather than use of the capital markets, are impacting the health of European banks. There are many reasons why Europe is so dependent on banks. Among them is the fact that, outside of the largest of banks, transnational banking is itself a relatively new concept, boosted by the EU and its common currency. Even banks based in countries that do not use the euro, such as the U.K. and Switzerland, benefit from the fact that so many other countries are using the euro, as it reduces the number of currencies used. European banking evolved in an era where each country had one or two “national champion” banks and a few smaller banks that typically operated in just one region or province.

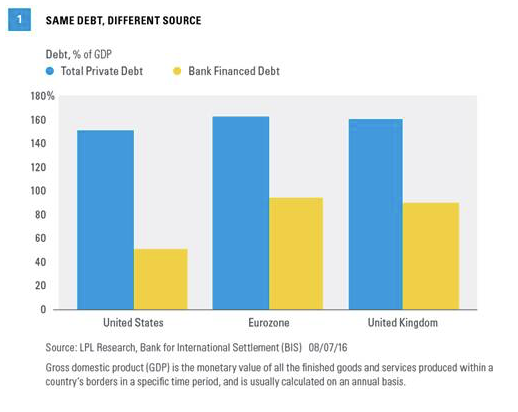

Further explaining the importance of banks to Europe are the higher savings rates relative to the U.S. [Figure 2]. Different countries have different savings rates, even within Europe. Polonius also warns that “borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry”—the management of resources, primarily land and livestock in Shakespeare’s day. Judging from the economic health of many of the highly indebted countries, maybe they should have heeded the warning.