The Covid-19 pandemic unleashed not only death and disruption but economic contradiction: a K-shaped recovery of haves and have-notes. Parts of the economy cratered while other parts, especially in technology, thrived.

The first six months of 2022 have upended the economic order once again. Naysayers who warned about inflation for years were finally vindicated this year after it reached 8.6% for the 12 months ended in May. Value stocks staged an impressive comeback, while tech shares swooned and bitcoin lost two-thirds of its value from November to June.

To view FA's 2022 RIA Ranking, 50 Fastest Growing RIAs and Discretionary and Non-Discretionary AUM, click here.

Ultra-speculative sectors like meme stocks and SPACs have generated huge losses. The broad stock market has sputtered, too, of course, as investors wave the surrender flag in the face of higher consumer prices, soaring gas prices and a Federal Reserve with an itchy trigger finger. Bond yields have risen accordingly, and the yield curve this year finally flirted with the inversion dance that most economists say augurs recession.

The RIA space has its own set of challenges to contend with now that the market has declined. Valuations in this space have exploded over the past several years to multiples of more than 10 times cash flow as increasing asset values led to rocketing profits. It also helped that interest rates were so low, which meant it was a good time to finance deals.

At the same time, the industry was graying and facing a succession planning problem: scads of advisors who had spent their lives being rainmakers at their firms suddenly wanted to cash out and relax. A threatened increase in the tax regime also led to a flood of firms coming to market, eager to cash out before their sellers got clipped by capital gains taxes.

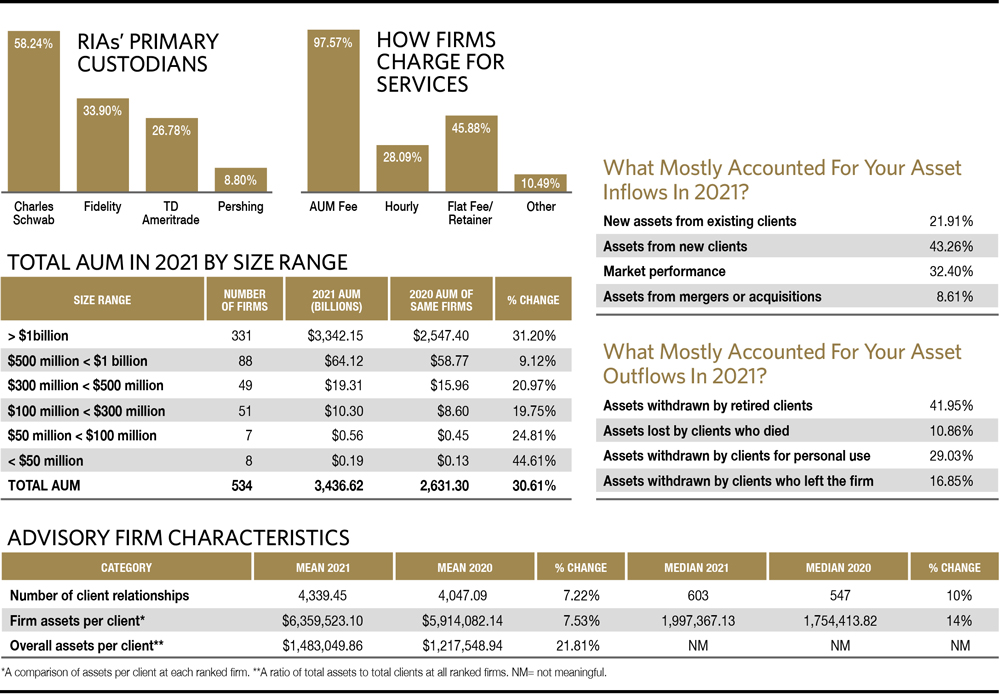

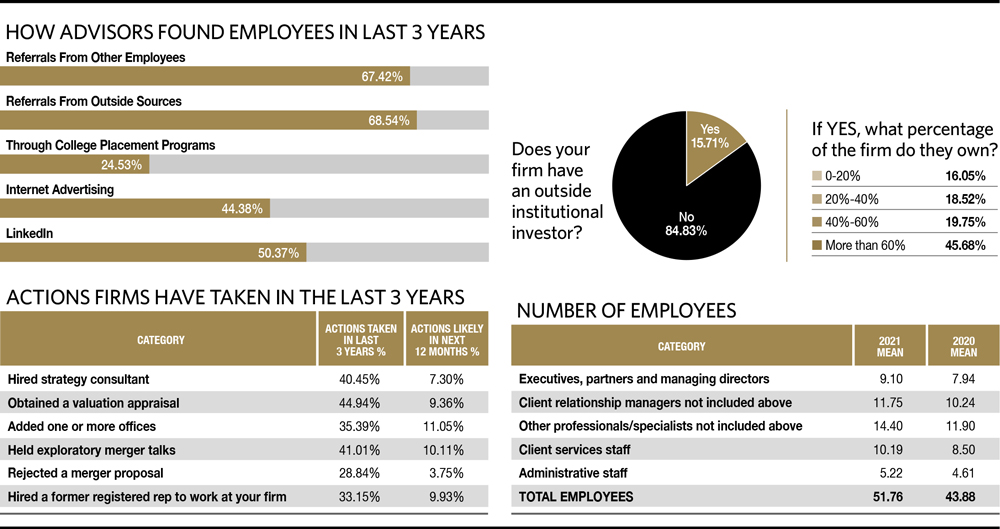

But even more important: The high valuations were also a result of all the institutional money watering the space. “If we indeed go through a recession, this will be the first time when we actually test how the industry behaves when it has an ownership consisting of both institutional capital as well as private capital owners,” says Philip Palaveev, the founder and CEO of the Ensemble Practice (and a Financial Advisor magazine contributor). He points to the results from this year’s RIA survey results suggesting that 42% of the top 100 firms have institutional ownership. That number would likely be higher if the firms were being more candid, he contends.

According to David DeVoe at DeVoe & Co., an investment bank and consultant that facilitates mergers and acquisitions, the number of deals has not yet slowed or reflected the market fears. “Technically in the marketplace, we have not seen a decline. … We have not anecdotally seen any compression in valuation. That said, the arrows in the marketplace are pointing more downward regarding valuation than upward.”

His first quarter report finds midsize and smaller sellers spiked in the first quarter: “Sellers with less than $1 billion in AUM increased to comprise 70% of all transactions for the first quarter, a significant uptick from 59% in 2021,” the report said.

DeVoe said that consolidators drove most of the M&A activity in the first quarter, picking up 55% of sellers. The list is dominated by many of the usual suspect acquirers, including Beacon Pointe Advisors, Creative Planning, Mercer Advisors, Mariner Wealth Advisors, Cerity Partners and Wealth Enhancement Group.

Scott Slater, an M&A specialist at Fidelity Institutional and vice president of practice management and consulting, says about the M&A environment this year, “Through May, we’ve seen 93 deals in our reporting, which is up 29%, largely because you’re seeing smaller transaction activity, but even the client AUM is up 12% to $135.2 billion. So it’s still up and going.” Fidelity’s report found that some of the biggest players are driving activity.

Critics say RIA firms have been able to paper over what is actually slow growth with inflated asset prices and bigger AUM fees. If assets are now declining, firms that aren’t growing are going to be exposed—and at a time of higher fixed costs, specifically the cost of employees who have suddenly become very expensive. “There’s been a reprice on talent,” says Palaveev.

“We, as I am sure others are as well, are experiencing challenges in hiring talent with the nationwide labor shortage,” says Marty Bicknell, the CEO of Mariner Wealth Advisors, based in Overland Park, Kan. “There has definitely been a shift to where it is now a candidate’s market, regardless of the industry. As we have continued to place focus on growth and look to add advisors and talent at the HQ level, we are experiencing this extremely competitive market firsthand. We have noticed that candidates are receiving multiple offers, and as the talent pool shrinks, compensation is more aggressive.”

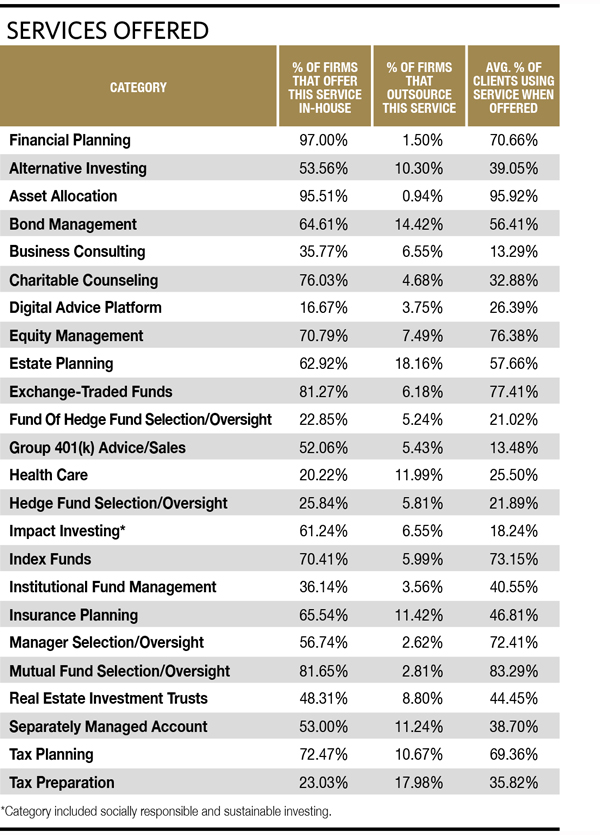

With their lives destabilized by the pandemic, clients have become more demanding about holistic advice. That means firms have had to add services to make their relationships stickier.

Several executives interviewed by Financial Advisor say that there’s been no fee or margin pressure in the RIA space of the sort the broker-dealer and investment management industries have faced. But margins are under pressure because RIA firms are being asked by clients to stuff more services into their bundle: Tax prep. Estate planning. Trust planning. Healthcare services. If you can’t buy these services from third party vendors, you might have to merge with them.

Deb Wetherby’s firm Wetherby Asset Management merged with Laird Norton Wealth Management (a deal announced in February) in a partnership of equals, forging a $15 billion firm. The deal was partly done, Wetherby says, so her firm could add services such as a trust department and philanthropy help (as well as build scale).

“As the talent market gets more competitive, you have to be able to retain your team,” she says. “Doing that requires more than just compensation. For us that whole thing was motivated by a recognition that having a little more scale would help and being able to offer more to clients, whether it’s in philanthropy or trust services or wealth planning or investment management. Clients are really going to love that.”

A lot of firms are desperate for talent, Wetherby says. She hired a firm to do an outside study and found that people are looking for 30% to 50% bumps in their base salary for lateral moves, when it’s usually 10% or 15% for the same job. That’s big when people are the biggest line item—usually 75% to 80% of a firm’s expenses. And it can especially hurt for firms with simple AUM fee structures that don’t also mix in some retainer models, she says.

Chris Zander, the president and CEO of Evercore Wealth Management and Evercore Trust Co. in New York, says his firm’s trust offering has been a key element to its growth strategy and the attraction of talent to the firm, since trust services are a critical component to every family in the ultra-high-net-worth category, those with $10 million or more. “You’ll see that firms doing lots of acquisition are starting to add that component, which we not only have, but across our footprint.”

Zander maintains that if you’re delivering in a comprehensive way with wealth management and trust services, beyond investment management, he says there is less pushback from clients on fees. “The clients will see the value whether it’s investment returns, whether it’s tax planning, whether it’s dealing with all the issues that take a lot of time, being the interface with their other advisors—their attorney, their accountant—coordinating all of those activities, there’s a time value, an assurance value to that that they’re looking for.”

Adam Birenbaum, the chief of Buckingham Strategic Wealth, says that the future of the RIA industry is the democratization of the business. “So anybody who is talking about cutting out services,” he says, “does not actually understand that adding more and more value to the lives of others is the future of our business. Those that look at it from a traditional commercial or corporate lens as it relates to high margin business [don’t] understand that they won’t have the clients to extract margins from if they do not continue to maneuver their businesses to be family offices to Main Street.”

Private equity firms may have reputations as asset strippers, but they have become sophisticated investors in the wealth management world. They know RIA firms are service-oriented, relationship businesses. It’s not necessarily a leaner, higher profit margin that these investors are looking for. A firm with a 60% net profit margin could be understaffed, something PE firms know, DeVoe says.

“If you’re trying to improve your margins you drop the business lines; if you’re trying to gain market share you add business lines,” says Peter Mallouk, the president and CEO of Creative Planning in Overland Park, Kan. “Now, I think removing business lines is shortsighted. I think that’s what the marketplace demands. … I don’t think [firms] necessarily have to prepare a tax return, but they have to be able to give tax advice.”

Less Turnover

Palaveev says that advisors tend not to turn over in the RIA space quite as often. Until recently, that has kept salaries from rising.

“When there’s more turnover, there’s more tendency for prices to reflect the market,” Palaveev says. “Markets with low liquidity are not always priced right. In the labor market, liquidity means people changing jobs. I believe that’s why we didn’t see much increase in compensation to advisors for the past five years or so, even though profitability went up, even though inflation went up … and [yet] still salaries were very stagnant. Part of that is that there is no pressure to reprice your talent when your talent is not leaving.”

During the financial crisis, many financial advice firms were privately owned. When faced with revenues severely reduced by the 2008 recession, some focused on cutting back salaries or staff (or getting rid of the free stuff).

But now the industry has uptown problems: The new private equity owners haven’t just bought assets. They’ve bought relationships. The distorted image of PE pirates looting and cutting costs to slim a firm down for a sale in five years doesn’t make sense here, industry watchers say. DeVoe says that the image cultivated by executives like “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap at industrial companies does not and cannot apply.

“Many of us have read Barbarians at the Gate and we’ve seen Chainsaw Al, and that approach is to buy, potentially lever up, cut expenses and then flip the organization,” says DeVoe. “We haven’t really seen any of that in this industry for good reason.” Typically it happens in more challenged industries where the growth has stalled, he says. “And this industry is vibrant. … This industry should frankly be growing faster than it is on a true organic basis.”

Most institutional investors are learning that the value of RIAs can vary widely depending on the characteristics of individual firms and their clients. Firms with younger client bases and advisors in affluent regional markets tend to have much greater growth potential, and receive higher valuations, than those with older advisors and mature clients in areas with stagnant wealth creation.

The number of RIAs is certainly growing. Fidelity’s Slater says “concentration” is a better term than “consolidation” for RIAs since the barriers to entry remain low and the RIA space is getting crowded with new entrants all the time. McKinsey & Co. said in a report on its website in August 2021, “More than 2,000 of today’s 6,000 retail-focused RIAs were created since 2016, and about 700 new RIAs are started each year.”

People have imagined a time when the RIA space’s top players will resemble accounting’s Big 4. But Slater says that time appears to be fairly far off given all the new entrants.

Meanwhile, as more broker-dealers get into the fee-only act, according to Cerulli Associates, RIAs have been forced to respond by adding services.

It’s not something that bothers Eric Kittner, the CEO of Moneta in St. Louis. “We don’t see a whole lot of competition on the hybrid side.” However, he says, there’s general competition from all parts of the RIA space. “I don’t see fee compression as a problem. Where we’ve seen it is ‘service creep.’ That is, you’re doing more for your clients than you anticipated 10 or 15 years ago. Yet you haven’t necessarily adjusted the fee schedule.”

But there’s a certain bedrock of pricing power, he says. Clients who want to delegate their financial directives to somebody else are generally willing to pay for it and aren’t as sensitive about the prices they are paying, he says, any more than customers turn up their noses at more expensive coffee from Starbucks.

Big Fish

Slater says it’s increasingly a large group of consolidators doing most of the M&A deals. “We look at firms that have done three or more deals in a 12-month period and there are 20 firms within that group right now which are driving most of the deals,” he says. “But you’re talking about some very different business models and approaches, and I think that tells you this is not just about scale. Scale is only one piece of it. This is a relationship-driven business.”

Brent Brodeski, the founder and CEO of Savant Wealth Management in Rockford, Ill., also took on institutional help this year for a cash infusion: a minority stake from Kelso & Company, which bought a 20% piece of Savant. Brodeski says Savant is going to use $15 million and invest it in the business this year now that there’s more capital to play around with.

One of the firm’s big buys was a fintech firm: Savant spent $3 million for a stake in Lumiant, an Australian fintech company whose software focuses on things like client values and goals first. It is designed to engage those client family members not as directly absorbed with the technical aspects of portfolio management or taxes. Advisors have to be able to scale business off these softer planning problems, like clients’ concerns about their health, Brodeski says, before bringing in ETFs and tax planning and estate planning documents. He says most advisor portals “suck” and he wanted to do something about it.

One of the firm’s big buys was a fintech firm: Savant spent $3 million for a stake in Lumiant, an Australian fintech company whose software focuses on things like client values and goals first. It is designed to engage those client family members not as directly absorbed with the technical aspects of portfolio management or taxes. Advisors have to be able to scale business off these softer planning problems, like clients’ concerns about their health, Brodeski says, before bringing in ETFs and tax planning and estate planning documents. He says most advisor portals “suck” and he wanted to do something about it.

Creative Planning’s Mallouk embarked on the acquisition trail several years ago and believes many firms remain open to a transaction. “We ourselves bought about a dozen firms in the fourth quarter, which was crazy.” He said the activity slowed down in the beginning of the year, but he’s still seen a lot of people continuing to sell. “I think what they’re finding is that the markets are shaky. ‘I’m not going to take anything for granted. The capital gains rate is still low. Valuations seem to be holding.’ There’s more RIAs today than there were a year ago because there are so many RIAs opening up. So you still have an incredibly highly fragmented space. So we’re seeing more for sale all the time. So it’s a lot of opportunity for a buyer who knows what they’re doing.”

The number of huge firms means there’s now a race underway to be the dominant national player in the space, he says. But he agrees many sellers have a problem that many custodians have recognized for years—most of them are not growing.

“The market has hidden their sins,” he says. “What if the market goes the other way for three years?”