Key Points

1. Cyclicality is a feature of both atmospheric conditions and investment performance. The historical record promises that for value investors, summer will follow winter—the challenge is in weathering the passing blizzard of negative returns.

2. Both U.S. and developed-market RAFI™-based strategies have outperformed their cap-weighted value benchmarks over the long term and on a 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year trailing basis.

3. The largest and most persistent investment opportunity is long-horizon mean reversion, which explains the historical outperformance of RAFI and supports our expectation that the dynamic value tilt of fundamental-index-based strategies will generate future excess returns over the long term.

Both of us are European-born and have a particular appreciation for kitsch-y Americana and its sunny outlook, perhaps as a reaction to our more neutral (some might argue, existential and heavy) cultural heritage.1 High in the firmament of traditional Americana are the “Greetings from” postcards depicting cities and sights from around the United States—although we have noted the enthusiastic adoption of this quaint piece of memorabilia by other locales around the world. The one characteristic shared by all such postcards is the absence of the gloom and grey of winter!

Investors, like all Earth’s creatures, experience “winter”—sometimes as unseasonably long—in asset classes, sectors, strategies, and regions that can stay out of favour for months, years, and even decades. After years of living in Boston, New York City, Paris, and London we can attest that, whereas all four are exciting places to work and live, perfect blue skies and warm sunny days are not permanent features of these cities. While their winters can be unforgivingly harsh and cruelly demoralizing, they are also home to glorious springs, magical summers, and riotously colourful autumns. The same is true in investing. Just as surely as summer follows winter, so too do unpopular strategies and asset classes enjoy their day in the sun.

Investing Seasons

We at Research Affiliates are value investors with a long-term contrarian perspective. We seek securities, asset classes, sectors, and regions that are unloved and undervalued, investing in and overweighting them the more unloved and undervalued they become. Our strategy has a seasonality all its own, just like most reliable sources of long-term excess returns we’ve come across. Although seasons in investing may not conform as neatly to calendars as they do in the physical world, they are undeniably real, with excess returns oscillating between harsh winters and balmy summers.

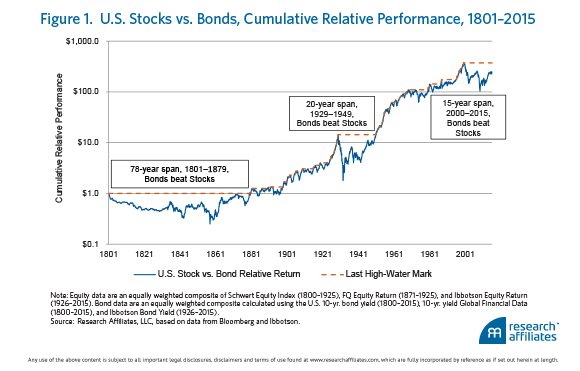

Starting from a broad vantage point, let’s compare the cumulative excess returns of U.S. stocks versus U.S. bonds over the 215 years from 1801 to 2015, as shown in Figure 1. Stocks underperformed bonds for 15 years or more in three instances over this lengthy horizon: a 78-year period comprising most of the 1800s, the 20 years following the Stock Market Crash of 1929, and the last 15 years from 2000 to the present day. Nevertheless, we don’t believe most reasonable investors would argue that abandoning equities entirely as an asset class makes a lot of sense for a diversified long-term portfolio.

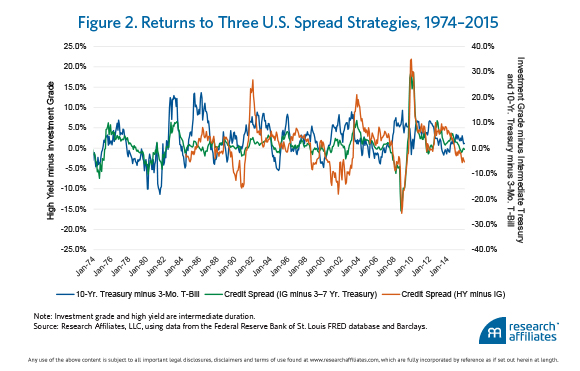

This same seasonality repeats in just about every strategy and sector of the market. Three simple, straightforward spread strategies clearly show the ebb and flow of returns. Figure 2 plots the term premium in U.S. Treasuries (long the 10-year rate and short T-bills) along with two credit spread strategies (long investment-grade credit and short 10-year Treasury, and long high-yield credit and short investment-grade credit). Admittedly crude, and only approximating actual investment strategies, they speak volumes about the functioning of financial markets. All three strategies made good sense over periods as long as multiple decades, accruing returns throughout the entirety of the time series, in no less than 60% of all monthly rolling one-year time windows. Yet notice the cyclicality in returns—even for the innocuous term-premium strategy—with annual reads of plus and minus 10% not being out of the ordinary.

The same pattern is present in equity market strategies, a prime example being value-minded strategies whose cyclicality we’ve described in the past as “unreliably reliable”; thus, in our view, distinguishing between weather and climate is a worthy endeavour. Weather is atmospheric conditions over a short period of time, whereas climate is atmospheric “behaviour” over relatively long periods of time. Cyclicality is an inherent feature of investing (climate), with sometimes volatile swings in returns (weather) over each cycle. But none of this, on the face of it, suggests a strategy is good or bad. It just means staying the course will be more or less uncomfortable. Thus, to assess the intrinsic performance attributes of a strategy requires a long-range perspective.