For better or worse, the latest developments from the coronavirus outbreak have focused a lot of investor attention on the U.S. stock market. That makes sense, given that the S&P 500 Index set a record high just a week ago but then fell more than 2.5% in consecutive sessions for the first time since 2015; President Donald Trump and aide Larry Kudlow are suggesting that investors buy the dip.

The $16.7 trillion U.S. Treasuries market doesn’t offer much guidance on whether the swift risk-off reaction is justified. As I wrote earlier this week, no record is safe in the world’s biggest bond market with so much uncertainty about how the coronavirus will dent the global economy. But just as important, Treasuries have been rallying for more than a year, even as equities soared, in no small part because of longer-term concerns about global growth, inflation and the limitations of developed-market monetary policy near the lower bound of interest rates. It shouldn’t be all that shocking that the benchmark 10-year yield touched 1.31% on Tuesday, a new low.

What, then, can investors use to gauge risk tolerance in markets? I’d suggest corporate bonds, which offer some clues that there’s more pain ahead.

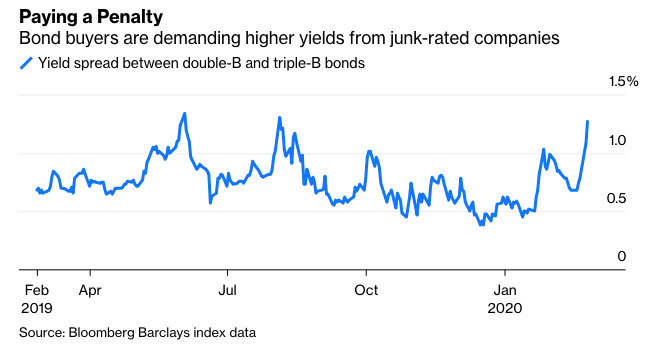

Just like stocks, the credit markets reached unprecedented levels toward the end of 2019. On Dec. 18, the difference between double-B and triple-B corporate bond yields fell to just 38 basis points, the smallest on record. That meant investors were hardly differentiating between securities rated below investment-grade—otherwise known as junk—and those that still maintained investment-grade quality. I asked at the time: What does a junk bond even mean anymore?

I wasn’t the only one shaking my head at that spread. Jeffrey Gundlach, DoubleLine Capital’s chief investment officer, highlighted the phenomenon during his annual “Just Markets” webcast last month, calling double-B corporate debt “one of the worst investments in the bond market.”

“I think you’re much better off owning triple-B—I don’t even like triple-B — but I don’t like double-B corporate bonds,” he said on Jan. 7. Just to hammer home the point, he added: “Stay away from double-B corporates is my message.”

Any trader who heeded that advice has won big in the past several weeks. The spread between double-B and triple-B bonds is now 127 basis points, the widest in more than six months. It jumped 19 basis points on Tuesday, 22 basis points on Monday and 21 basis points on Jan. 27, three days dominated by investor angst over the spread of the coronavirus. The only other comparable moves in the past year came in August, when U.S. recession fears peaked.

Gundlach called the widening since December “a big crack in risk asset confidence” in a Twitter post on Monday.