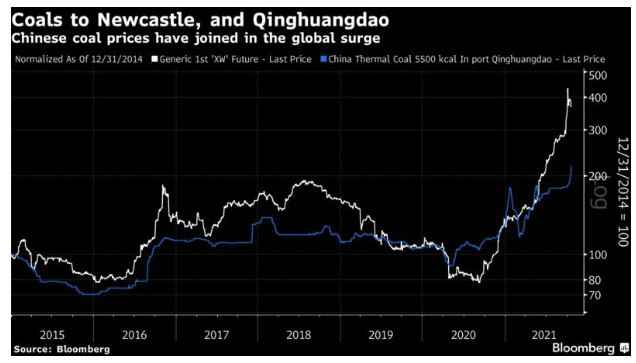

Why is this happening? It looks as though China’s fuel crisis, which saw power outages last month, has much to do with it. The price that businesses must pay for coal hasn’t risen as dramatically as in western Europe, but it has still more than doubled since early last year:

A recurrence of Covid shutdowns has also weighed. There are thus some reasons to believe that growth can pick up again. This might help to explain why the Chinese data didn’t spark a “risk-off” reaction in American and European markets this week; it also suggests that a dose of such sentiment could still lie ahead if growth doesn’t turn around.

Money Supply

After the financial crisis in 2008, the PBOC in many ways came to the planet’s rescue by engineering a massive spurt of liquidity, while U.S. money supply was constricted. For the decade since, the rest of the world has been plagued by concerns that this debt overhang will lead to a Lehman-style crisis. The PBOC has been prepared to release liquidity when trouble threatens, as during the devaluation crisis of 2015, and last year during the pandemic. But policy makers are plainly anxious to rein in credit, and show no great desire to stimulate the country’s way out of the current slowdown. For the first time in a quarter-century, the supply of money is growing much faster in the U.S. than in China:

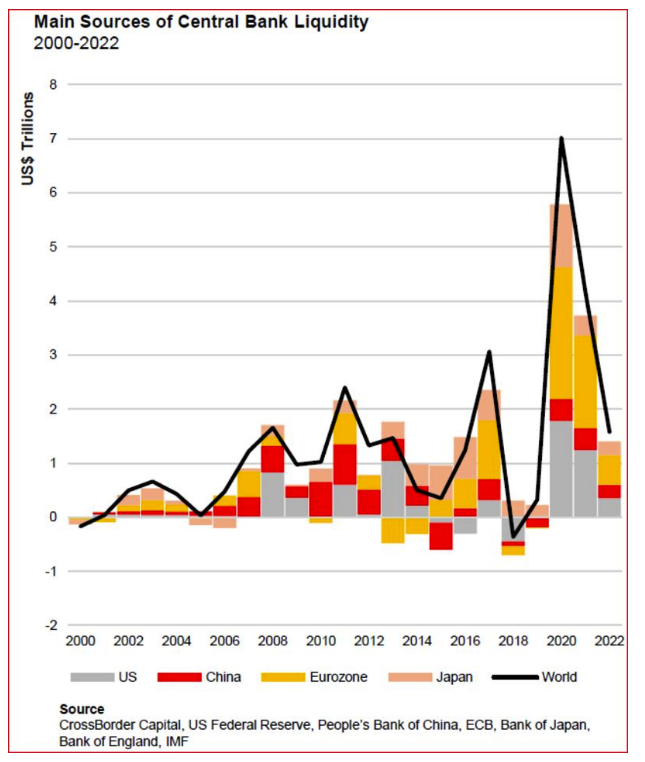

Accepting a slower rate of growth in return for reducing the risk of a credit crisis may well be sensible policy for China, but it will have effects elsewhere. The following chart from CrossBorder Capital Ltd. of London breaks down the world’s main sources of central bank liquidity since 2000. The PBOC played a vital and consistent role in the years before and after the crisis. It is now stepping back. The likely reduction in the amount of central bank liquidity over the next two years is on the face of it a reason to brace for slower growth, and for the risk of accidents as debt around the world grows harder to refinance:

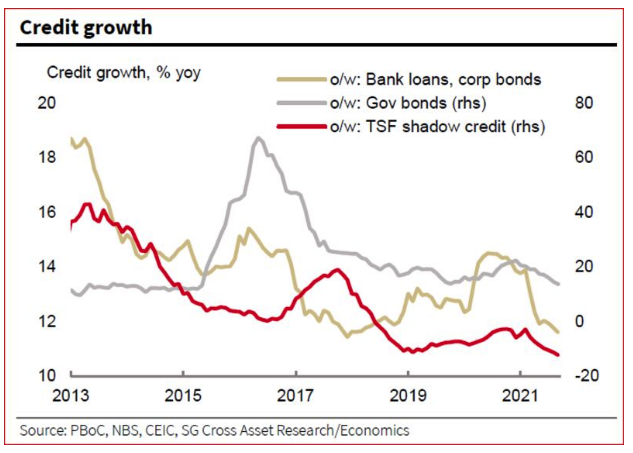

Looking across the different credit channels in China, this chart from Wei Yao of Societe Generale SA shows that all are tightening:

With evidence of slackening economic growth, this looks like an unduly Spartan approach. Several economists suggest that the PBOC will be forced to ease policy before the end of the year. As it stands, liquidity is tightening and likely to tighten further.

If there is a reason to believe that growth won’t return to the kind of 6%-plus rate to which the rest of the world has become accustomed, it lies in monetary policy. The People’s Bank of China controls many levers over money supply and this has risen dramatically over the years, as might be expected to enable China’s phenomenal growth.