Bond investors must be gluttons for punishment. Last year was one of the worst on record for the Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Index, which fell 1.89% as yields shot higher. Factor in inflation of 7%, and the real decline was closer to 9%. This year is even worse, with the index already down 3% through Tuesday. And yet, like an aging champion boxer who doesn’t know when to quit, traders keep answering the bell.

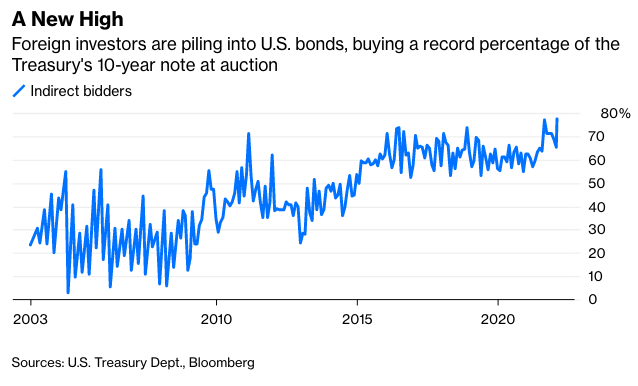

That was evident in today’s government auction of $37 billion in 10-year notes, which was stellar no matter how you look at it. In a sign of big demand, the securities drew a yield of 1.904%, below the 1.926% level that they were trading at in the so-called when-issued market just before the auction. Not only that, but investors submitted bids for 2.68 times the amount offered, a level exceeded only two other times for that maturity going back to early 2017. (The securities are auctioned monthly.) Want more proof? Indirect bidders, a group associated with foreign central banks and other big institutions, were awarded 77.6% of the securities offered, a record in data going back to 2003.

What’s truly amazing is that all this demand came one day before the government is forecast to say that its primary measure of inflation, the consumer price index, surged 7.2% in January from a year earlier, the biggest increase since 1982. For the non-bond geeks, inflation is like kryptonite because it erodes the value of bonds’ fixed-interest payments. And, of course, the Federal Reserve has made it clear that it plans to start raising interest rates next month and end its quantitative easing program, which is a technical way of saying it will no longer support the market by buying bonds.

To understand what may be happening, it helps to realize that when it comes to the bond market, it’s all relative. What that means is that it matters little where absolute yields are trading; what matters more is where yields are relative to the alternative. In that sense, there are no good alternatives to the U.S. bond market. Yields on U.S. Treasuries of all maturities average around 1.14 percentage points above securities from developed economy governments elsewhere in the world, according to ICE BofA indexes. That difference has expanded from 0.22 percentage point in April 2020. German 10-year notes yield 0.21%, while similar maturity securities in the U.K. are at 1.43% and are 0.21% in Japan.

And it’s not as if these foreign institutions, especially banks, can put their money anywhere else. Thanks to reforms put in place after the financial crisis more than a decade ago—the Volcker Rule, the Dodd-Frank Act, Basel III—most big lenders must keep a sizable portion of their reserves in the safest of assets. And nothing is safer than risk-free Treasuries.

There’s also a currency play here. When foreign investors put their money in dollar-denominated assets, they benefit from the greenback’s appreciation. And the U.S. dollar has been a stellar performer of late, with the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index having risen 5.21% since late May. There’s no guarantee that the dollar will keep appreciating, but currency strategist surveyed by Bloomberg predict gains the rest of the year.

People have been wrongly forecasting the end of the bull market in bonds for much of the past four decades. And they may finally be right this time, but sometimes the old champion still has a few tricks up his sleeve. Don’t forget that George Foreman became heavyweight champion of the world for a second time at the ripe old age of 45.

Robert Burgess is the executive editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.