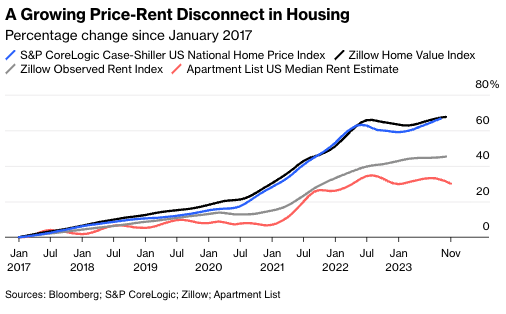

Market rents in the U.S. are, depending on which measure you look at, either rising slowly or falling outright. Home purchase prices, after a slight dip last year, are climbing again. Prices and rents seem to have disconnected early in the Covid-19 pandemic, and that disconnect has mostly grown ever since.

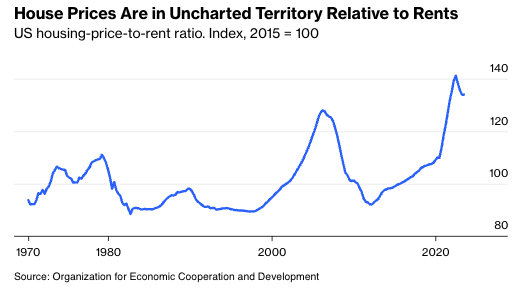

Take a longer view, with the ratio of U.S. home prices to rents calculated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and prices are historically high—with the price-rent ratio about 6 percentage points higher than in the lead-up to the housing price collapse of 2006 to 2011.

Rents are to house prices what dividends or earnings are to stocks—the flow of income that justifies the value of the asset. When prices and rents get out of kilter, something presumably has to give eventually. As Federal Reserve Board economist Joshua Gallin put it at the June 2005 meeting of the interest-rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, “rents provide a loose tether for house prices; prices deviate from their long-run relationship with rents for extended periods, but not indefinitely.” About a year and a half after that, US house prices began a five-year, 26% slide, going by the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index.

Are we in the midst of another such housing bubble, with a price collapse on the way? The current consensus seems to be no, and while the consensus is often wrong, there are reasons to question the story told by the price-rent chart. Most have to do with the fact that accurately measuring the price-rent ratio is difficult. Thanks in large part to the methodological work of economists Karl Case and Robert Shiller, we now have a pretty good handle on developments in the sale prices of single-family homes through the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller indexes, the Federal Housing Finance Agency price indexes and newer private measures from Zillow and, as of last month, Redfin. Until pretty recently, though, the only high-frequency data series available on rents in the US was the rent measure in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index, which is what the OECD uses to calculate its index of the price-rent ratio.

As inflation watchers have become quite aware over the past couple of years, CPI rent lags changes in market rents by a year or two because it’s intended to measure everybody’s rents and not just those of new tenants. But because the OECD also uses a lagging index for US housing prices—the FHFA all-transactions index—the effect on the price-rent ratio seems to be a wash. Economists at the BLS and Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland last year devised a New Tenant Rent Index, based on the same survey from which CPI rent is calculated, that the BLS is now releasing quarterly, with data going back to 2005. When I calculated a price-rent index based on the non-lagging FHFA purchase-only index and the New Tenant Rent Index, it followed virtually the same course since 2005 as the OECD price-rent index.

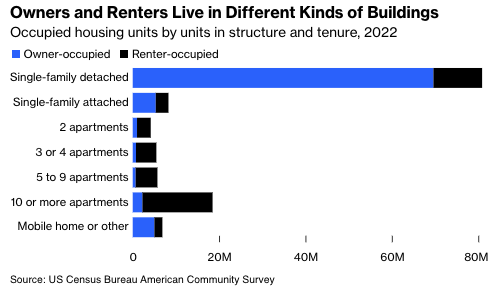

The bigger price-rent measurement issue seems instead to be that the housing available for rent in the U.S. is so different from the housing available for sale, with single-family houses mostly owner-occupied and units in multifamily buildings mostly rentals.

Amid a pandemic that first pushed people out of apartment-filled cities because of infection fears and the temporary halt of most activities that make cities attractive, then lured them out with the promise of continued remote work and the need for more home workspace, it shouldn’t really be a surprise that demand for housing to buy (what most single-family houses are) grew faster than demand for housing to rent (what most apartments are). Meanwhile, on the supply side, the number of new multifamily units under construction has been setting records while the number of single-family houses under construction has not. (Yes, I realize this is partly because it's been taking such a long time to complete multifamily buildings lately, but starts and completions have also been also higher relative to historical averages for multifamily than for single family.)