Before jumping right into housing affordability, it is necessary to consider the affordability of common stocks, investor interest and initial public offerings in the early 1980s through today. Back in 1982, stocks were the most affordable of my lifetime. I can remember pitching Coca-Cola (KO) to investors in 1981-1982 at six-times earnings with a 5 percent dividend. Only my father and cousin bought it. There was no demand for common stocks when riskless interest rates were offering double-digit returns. There was some issuance of new companies (IPOs) and secondary offerings of existing ones, because it was prohibitively expensive to borrow money at 15-20 percent.

Fast forward to 1996-2000, when Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan, coined the phrase “irrational exuberance” to acknowledge how nutty equity prices were. Price-to-earnings ratios (P/E) rose to the highest levels in our lifetimes and an enormous bubble in IPOs reached a crescendo in late 1999 and early 2000. Investors were firing stock pickers with above-average track records because their next-door neighbor was doubling their money on the latest dot-com wizardry. There was a peak in demand despite the worst affordability in 60 years. Affordability doesn’t dictate demand, demand dictates affordability. Eventually the supply of new shares from IPOs choked the stock market and it fell 40 percent over two-plus years.

During that same era of very high interest rates (1975-1987), when Coca-Cola was so cheap, single-family residences were historically unaffordable. This lack of affordability didn’t stop home buyers and builders from being very busy. The largest population group up to that time, the baby boomers, were buying homes to meet the demands of their growing families. Just like in stocks, affordability was not the deciding factor in the production of new homes any more than affordability drove common stock issuance.

At the height of the tech bubble in early 2000, single-family residences were relatively affordable. However, the United States was attacked on September 11, 2001, and in the aftermath interest rates were brought down by the Federal Reserve. Single-family residences became the investment of choice for boomers buying second homes and Gen-Xers buying their first or a trade-up home. Loose lending and maniacal behavior caused huge demand for homes and home builders met that misplaced demand by building the most single-family homes three consecutive years (mid-2003 to mid-2006).

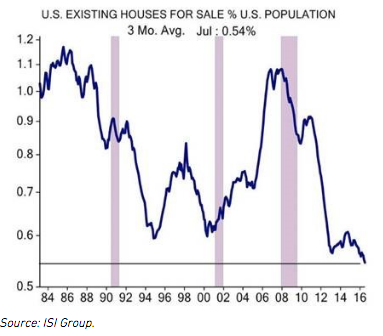

This takes us to the aftermath of the financial meltdown, which had among its main causes the mania in real estate that preceded it. From 2009 to 2013, homes were the most affordable in my lifetime (60 years). As you can see from the chart below, the availability of homes for sale, coming off five years of negligible home building, was the lowest in 60 years:

This chart shows that there is a severe lack of supply in homes and the owners (primarily boomers) are staying in their home much longer than prior generations. How would you have done if you bought home builders at the low points on this chart in 1994 and in 2000? The Case-Schiller chart below answers the question:

On both an absolute and per capita basis, we built the fewest single-family homes in 60 years in 2011. Affordability only becomes important when demand drives activity, otherwise it simply makes a good talking point. We can remember in 2010-2013 telling every young man and woman we could that this was as good a time to buy a home as has existed in my adult years. Warren Buffett wrote in his 2012 annual report for Berkshire Hathaway that if he were 25 years old, he would have purchased four homes, fixed them up and rented them. He would have done very well so far.

Watching today’s media coverage, one would think they are campaigning for this to be a cyclical top in home building and a cyclical top in prices. Their primary premise is two-fold: the demand for newly built homes is closely tied to interest rates and home price affordability. We are not mathematical geniuses, but the chart below doesn’t provide any reinforcement for their argument: