The Covid-19 pandemic was an unprecedented shock across the global economy. But the economic damage was met with an extraordinary global monetary response with central banks cutting rates to near zero levels and expanding balance sheets by nearly $10 trillion to provide additional levels of monetary accommodation. Moreover, governments around the world provided fiscal support and, on average, annual spending increased by 7% of gross domestic product (Bloomberg). As economies have recovered and the impact of Covid-19 fades, these extraordinary levels of monetary accommodation are no longer necessary, and thus we’re likely to see the active removal of monetary support. While these extraordinary fiscal and monetary measures certainly helped stave off broader economic weakness, these tailwinds are likely to become marginal headwinds to the global economy in the upcoming years.

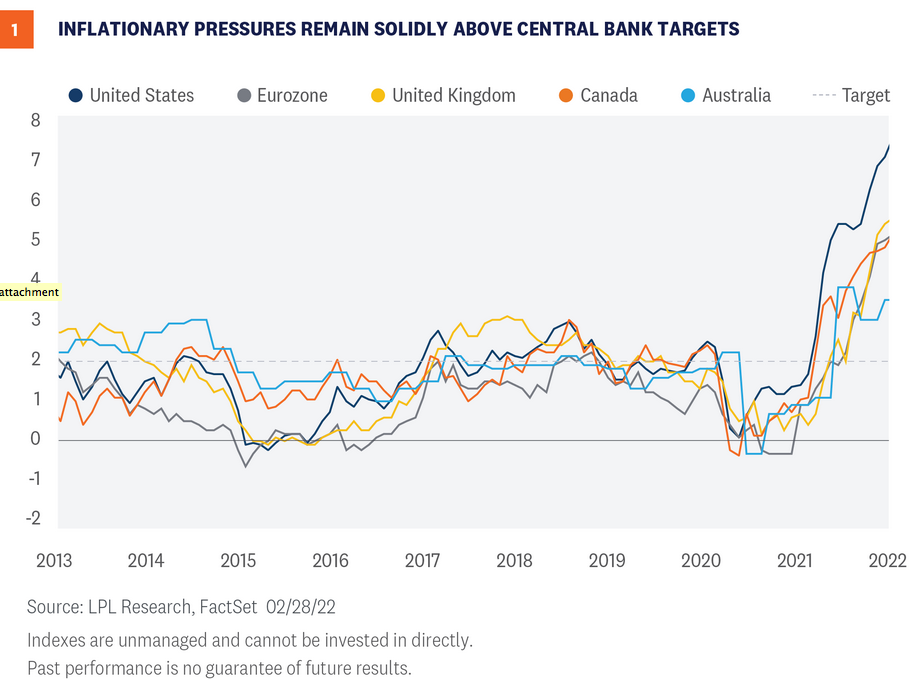

Additionally, a confluence of events has raised inflationary pressures to the highest in several decades. Direct fiscal stimulus gave discretionary funds to consumers, which instantaneously boosted demand, especially for consumer goods as most people were spending much less on services during the pandemic. The quick rebound in consumer goods spending put stress on the logistics and transportation sectors, crimping supply and thereby creating an upward spiral on prices. Moreover, due to continued price pressures (as defined by each respective country’s Consumer Price Index) that remain above central bank targets, global central banks began wrestling with the conundrum of a fragile economy coupled with rising prices [Figure 1].

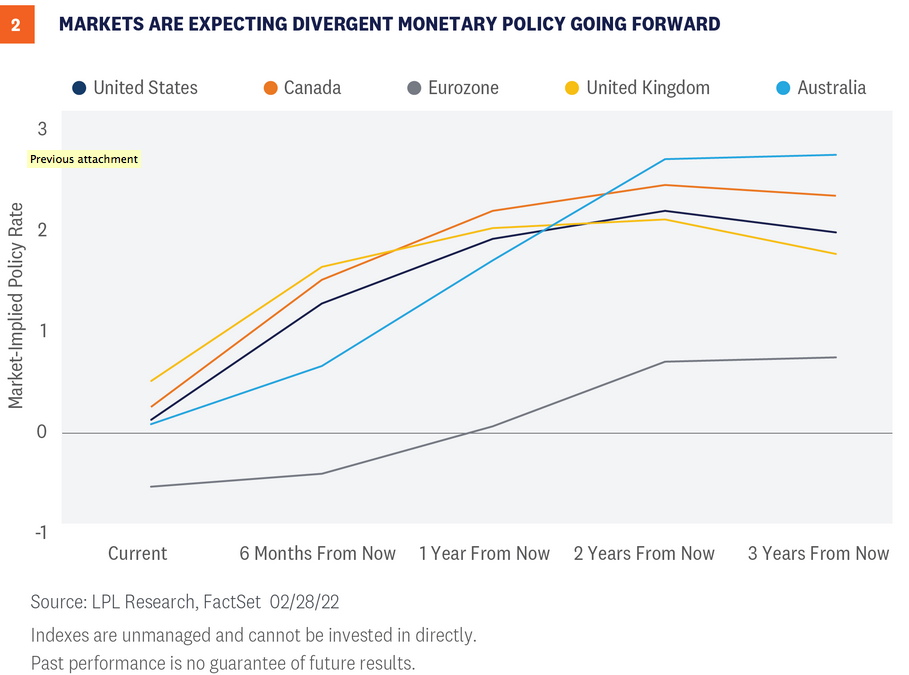

With inflationary pressures running higher than most central bankers are comfortable with, calls for interest rate hikes have become louder. A number of important central bank meetings are set to take place in March, including the Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Canada (BOC), Bank of England (BOE) and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). As such, March could be an important month for monetary policy shifts. And while many central banks have stopped providing forward guidance on an actual plan to raise short-term interest rates, markets have already priced in a number of interest rate hikes over the next 12 months. As seen in Figure 2, market expectations for rate hikes are broadly expected and include fairly significant rate hiking campaigns for the BOC, BOE, and the Fed over the next year. Markets expect these central banks to increase interest rates five to seven times over the course of a year, which seems fairly aggressive to us. Moreover, markets are expecting somewhat divergent policy rate paths after the second year of rate hikes. Specifically, markets are expecting the U.K. and U.S. to cut interest rates in 2024. Interest rate cuts tend to happen around broad market stresses or while at the precipice of a recession. It should be noted that these market-implied expectations are volatile and expectations can and do change over time.

Our view remains that interest rate hikes for the U.S. will likely begin in March with a 25 basis point (0.25%) hike and then three to four more rate hikes at subsequent meetings in 2022. Moreover, we think the Fed will start to reduce its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet in the second half of 2022. There is a risk to the upside (in hikes) depending on the trajectory of inflationary pressures. If consumer price pressures moderate over the course of the year, as we and the Fed expect, then we think the Fed and other central bankers can take a more moderate approach to interest rate hikes. However, if inflationary pressures remain stubbornly high and, importantly, we start to see longer-term inflation expectations become unanchored, central bankers may be forced to move more aggressively than what is already priced in.

That said, given the current conflict in the Ukraine, there remains considerable near term uncertainty with central bank intentions. Additionally, upward pressure on commodity prices, already impacted by Covid-19-related supply chain disruptions, may see a more sustained impact as economic sanctions play out and will probably be the main source of risk for possible broader economic repercussions. As such, inflationary pressures may remain high particularly as it relates to gas prices.

Finally, and we can’t stress this enough, these views and opinions are secondary to the conflict taking place in Ukraine. While our primary job is to provide investment advice, we certainly recognize that there is an immediate humanitarian crisis taking place in eastern Europe. We hope the conflict ends quickly and offer our thoughts to those impacted.

Lawrence Gillum is a fixed income strategist at LPL Financial. Ryan Detrick is chief market strategist at LPL Financial.