Inflation has been on the rise. Investors are not as interested in what’s happening now as they are in what’s happening next. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve (Fed) shared its views at the conclusion of its last policy meeting on Wednesday, June 16. And while the Fed’s position that inflation is likely to be transitory has become stronger, not weaker, Fed members have seemingly different opinions on the future path of monetary support.

Inflation has been on the rise. Everyone knows it and feels the impact with every purchase. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) spiked to 5.0% year over year in May, the most since 2008, while core CPI (excluding food energy) hit 3.8%, the highest since 1992. Inflation has been rising and the Fed is watching. How will markets react to any potential inflation over the next year?

We do know this: Markets will be looking forward, not backward. By the time something becomes a “thing,” a meme or makes a magazine cover, market participants are often past it, as we discussed in our June 16 blog, Why Inflation Worries Likely Just Peaked. Markets are no longer watching to see if inflation will spike. It already has. In fact, since the big upside surprise in the April inflation data, released May 12, many inflation-sensitive assets have been underperforming. Copper? Down. Lumber? Down. The 10-year Treasury yield? Down. Market-implied inflation rates? Down. Gold? Down.

At the conclusion of its last policy meeting on June 16, the Fed shared its view on what may be coming for inflation. In its updated forecasts, the Fed acknowledged it had missed on inflation expectations, upgrading its preferred core inflation forecast for 2021 from 2.2% all the way up to 3.0%. That’s a large jump, but that’s based on what’s behind us. The forecast for the same index in 2022 and 2023 scarcely moved, at 2.1% for both years.

Inflation is certainly still capable of coming in hotter than expected. The difference between now and earlier this year is that inflation expectations are already elevated. In order to see inflation assets really perk back up, we would probably need to see stronger signs that higher inflation may be persistent. To get a read on that, it may be better to look at prices that tend to be more stable. We know there are areas where we’re seeing extreme price moves, which is impacting broader measures of inflation. But what about prices that tend not to move? There is such a measure, developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, called sticky core inflation.

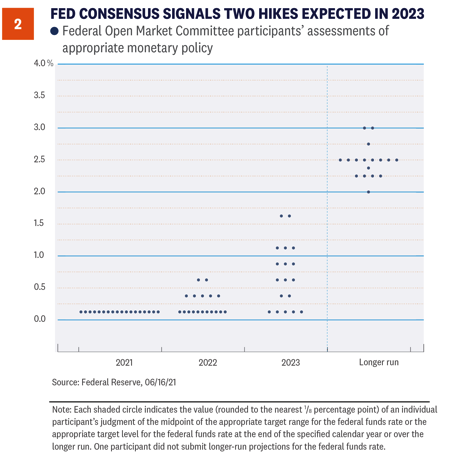

As seen in Figure 1, unlike CPI and even core CPI, sticky core prices are not setting multi-decade or multi-year highs. Sticky core CPI is up 2.6% year over year. The last time it was that high was…2020. There are still some warning signs though. While you have to be careful annualizing monthly data because it multiplies small, potentially meaningless, moves, annualized sticky CPI in each of the last two months was over 4% and that hasn’t happened since 1992. But even sticky core CPI has had some price idiosyncrasies in the current environment. If you take just the median move of the CPI components, the middle change for any given month, 12-month price changes have actually been declining. And the last two months? Somewhat elevated but nothing special.

We’ll be watching both sticky core CPI and median CPI to help monitor the likelihood that inflation will become persistent. We do think inflation will be elevated over the rest of 2021—and possibly into 2022—before it really starts settling down, but that’s still consistent with inflation being transitory. And it may remain somewhat higher after that compared to the last cycle as deglobalization and a potentially weaker dollar offset some of the structural forces that we think will continue to weigh on inflation. If inflation does start to look more persistent, it will certainly be felt on Main Street. For Wall Street, the immediate fear wouldn’t be the inflation itself, but rather its ability to force the Fed’s hand and accelerate policy tightening. But, based on how markets have been responding recently, the Fed’s position that inflation is likely to be transitory has become stronger, not weaker.

Speaking Of The Fed

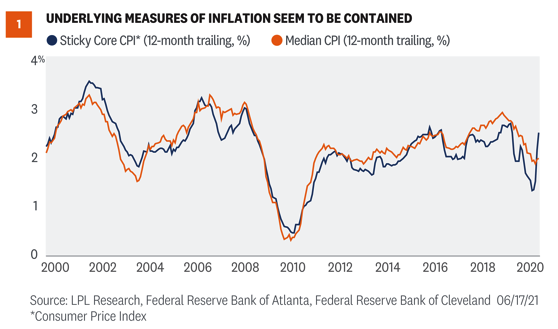

The Fed ended its two-day Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting last week and, as expected, there were no changes to its current interest-rate or bond-purchasing policies. However, signaling on the future path of short-term interest rates seemingly surprised markets because the number of Fed members who now expect interest-rate hikes in 2023 changed dramatically, relative to the last FOMC release. While an initial rate hike was once thought of as a 2024 event at the earliest, as seen in chart below, the majority of members now expect at least two quarter-point interest-rate hikes to take place in 2023. Additionally, seven members (out of 18) expect at least one rate hike in 2022.