In an earlier article, I asserted that investment advisors may quite regularly breach their fiduciary duty by failing to recommend an annuity when working with a certain type of client I call the constrained investor. In fairness, I cannot be too critical of advisors who until now have preferred to avoid annuities. The reason I can’t is that, historically, advisors had no convenient framework to work with that makes it easy to determine whom among their clients is or isn’t a constrained investor and, by extension, to determine which clients required the inclusion of an annuity.

In this article, I will define a framework. I will also expand on some of the risks that threaten constrained investors’ retirement security. These risks demand the advisor’s closest attention. And I will end this article with a call for all of us to rally around a new appreciation for how to best-serve the retirement security needs of a large and critically important segment of investors. This includes most women approaching retirement or recently retired. First, the risks.

Timing Risk: 'The 90-Day Rule'

Sequence-of-returns risk is a phenomenon that most advisors are familiar with. Many attempts have been made to illustrate the potentially negative impact of sequence-of-returns. Among these are scenarios illustrating side-by-side comparisons of annual investment returns. One scenario illustrates actual results over a lengthy period of years, and the other illustrates what would happen if the sequence of annual returns were to be reversed. The two net results can be dramatically different. Of course, that’s the point. These types of illustrations of sequence-of-returns risk can be effective, but I do not favor them. Numbers intensive, they can be confusing to some clients. Let me offer you another approach, one that any prospect or client can easily understand.

The Story Of 10 Retirees

As you look your prospect or client in the eyes, ask him or her to imagine 10 financially identical people. The 10 people are identical in the sense that all have the same $500,000 in retirement savings, all 10 have identical investment portfolios, and when they retire, all will withdraw the same amount of monthly income. What’s different among these 10 financially identical people? Only this: Timing.

To conceptually demonstrate the destructive potential of timing risk, we will separate their dates of retirement by a calendar quarter (90-days) until all 10 have retired. Then, we’ll look at what happens to them over the following 30-years.

The first individual will retire on January 1, the second on April 1, the third on July 1. It will continue in this fashion until all 10 are retired. Next, we will pick n historical, 2-year period to sequence the 10 individuals’ retirements. The example will use actual market values for this period.

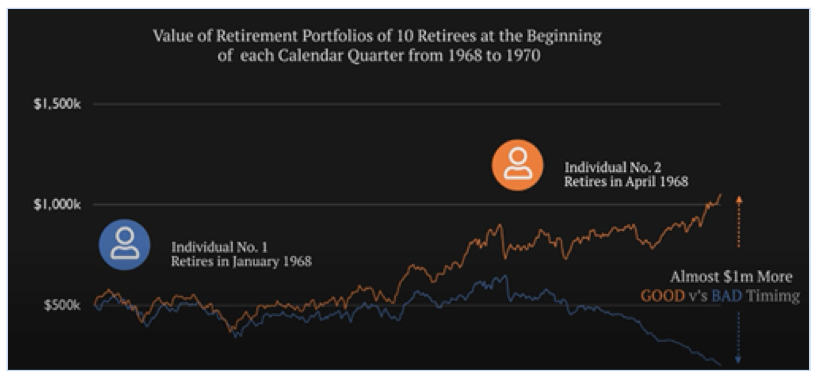

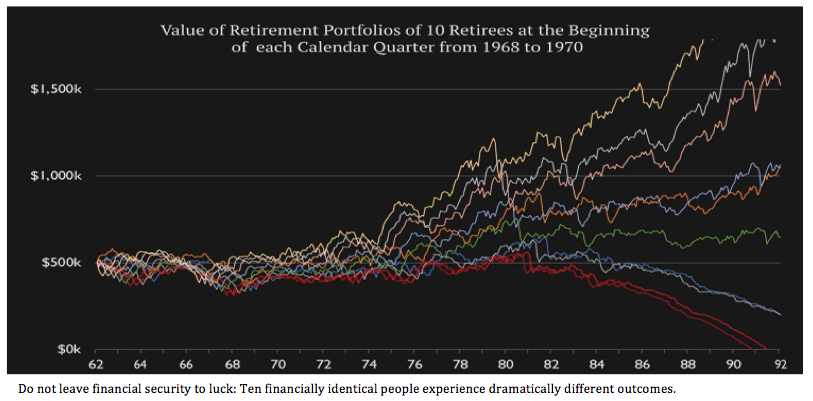

What do we learn? In short, we learn how utterly dangerous it is to leave a client’s retirement security to chance. Let’s focus on the first two people to retire. Call them Susan and Sheryl.

Sheryl, who retired second, ends up with almost $1,000,000 more retirement income than poor, unlucky Susan. If only Susan had waited until spring to retire—three months—her quality of life in retirement would have been enormously improved. But it’s even worse for the fifth retiree, Phil.

Phil suffered portfolio ruin. No income. No wealth. No luck.