Fans of the television series Kitchen Nightmares know the show’s formula. Chef Gordon Ramsay, the white knight of failing restaurants, rides in to help restaurant owners. Though initially resistant to change, they eventually embrace the revamped menu. That menu almost always has fewer dishes than the old one, allowing the owners to save money and operate more efficiently.

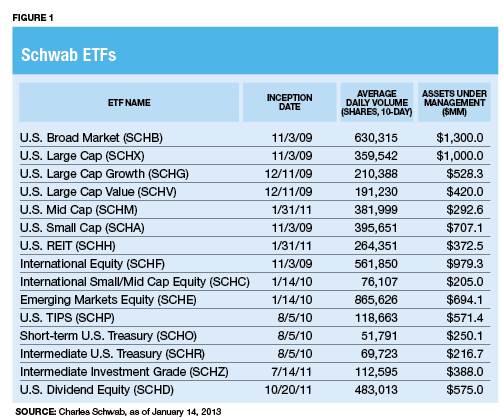

Charles Schwab & Co. is no failing restaurant, of course, but the formula for its family of ETFs has one thing in common with Ramsay’s recipe for success: Keep the menu short and simple. Instead of trying to provide access to every nook and cranny of the stock and bond markets, or devising new, improved indexes, Schwab’s 15 ETFs focus only on meat-and-potatoes core investment segments.

The limited selection keeps expenses at rock bottom levels and provides an advantage that competitors don’t have, according to Marie Chandoha, president and CEO of Charles Schwab Investment Management. She adds that the core sectors represented by the firm’s 15 ETFs cover the areas that investors want most, and customers can trade them commission-free online.

“When an ETF provider has a lot of smaller products, its cost structure becomes higher,” she observes. “We don’t have that problem because we’ve constructed an incredibly efficient ETF business covering only the largest, most popular investment categories.”

According to Lipper, nearly half of the 1,400 exchange-traded products on the market have less than $50 million in assets and 520 of those have assets of less than $25 million. Schwab doesn’t have any runts to tow along, since its smallest ETF weighs in at $199 million in assets.

But at the same time, the firm doesn’t have nearly the product breadth of larger competitors such as Vanguard, State Street and iShares, or the unique indexing methodology or investment strategies of smaller rivals. And its ETFs don’t provide access to increasingly popular alternative and satellite categories such as precious metals, commodities, single countries and currencies.

Still The Underdog

A Slow Build

Despite its aggressive fee structure, the firm is still very much an underdog in the ETF industry. It launched its own brand of ETFs in late 2009, years after its larger competitors jumped in. With $8.4 billion in ETF assets under management, it ranks 10th among ETF providers and claims less than 1% of the total market.

Todd Rosenbluth, an exchange-traded fund analyst at S&P Capital IQ, believes that while Schwab’s ETF business will grow with the industry, “it’s unlikely to take market share from Vanguard, iShares and State Street.”

Nonetheless, he says the pricing wars have raised the firm’s profile as a low-cost ETF provider. “As investors become familiar with ETFs, they’re going to be looking at costs, and Schwab wants to be part of that conversation,” he says.

Despite its small footprint in the ETF industry, the firm has been a major player in the ETF fee wars over the last few years. Schwab threw down the fee gauntlet back in November 2009 when it offered its broad U.S. stock market ETF for a basis point less than a similar offering from venerable low price leader Vanguard. In what looked like a game of cat and mouse, Vanguard responded by lowering the cost of that ETF by two basis points. Soon after, Schwab regained its position as the cheapest in the category by doing the same.

Since then, the good news on expense ratios has just kept coming as iShares, State Street, Vanguard and Schwab take turns making cuts. The pricing wars came to a head last September, when Schwab cut expense ratios on all 15 of its ETFs, making them the cheapest in their respective Lipper categories.

With a razor-thin expense ratio of just four basis points, the Schwab U.S. Broad Market fund (SCHB) and the Schwab U.S. Large Cap fund (SCHX) now claim the title of the cheapest ETFs in the industry. The former has $1.2 billion of assets under management, while the latter has $968 million. The company’s expense ratios range from 5 to 10 basis points for its four bonds ETF offerings, 4 to 10 basis points for eight U.S. equity funds, and 9 to 15 points for its three international ETFs.

As part of its expense cuts, Schwab usurped the title of lowest-cost emerging markets ETF provider when it lowered the expense ratio of its Schwab Emerging Markets Equity fund (SCHE) to 15 basis points. It took the title away from the hugely popular Vanguard MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (VWO), beating the Vanguard offering by 5 basis points. In an effort to lower licensing fees, Vanguard soon after that announced plans to move from the MSCI indexes that served as the benchmark for 22 of its index and exchange-traded funds to those constructed by the FTSE Group and the Center for Research in Securities Prices.

At this point, Schwab remains the low-cost ETF leader. But with expense ratios that are only 2 to 8 basis points higher for comparable products, Vanguard isn’t far behind, and its move to lower cost indexes could signal another fee chop is on the horizon. Chandoha declined to say whether Schwab is prepared to cut fees again if Vanguard or another competitor does, but she noted, “We will always be monitoring the fee landscape.”

The pricing wars—though none of the firms acknowledge them as such—underscore the role low costs play in attracting investors. According to an online survey of more than 1,000 investors with at least $25,000 in investable assets conducted by Schwab last year, costs are the No. 1 factor for investors looking at ETFs. Respondents said they paid the most attention to expense ratios, followed by trade commissions.

Aside from building its ETF lineup, Schwab has another, less obvious reason to keep low expenses in the forefront. By providing an entry point to other products and services, the ETFs serve as a tool to increase assets under management. Over the last few years, revenue from asset management and administration, which includes fees earned from the company’s ETFs and mutual funds as well as its fee-based advisory services, have become increasingly important to growth. In 2011, such fees represented 41% of revenue, making them its largest moneymaker. Trading fees, once Schwab’s bread and butter, accounted for a modest 20% of the firm’s top line.

Schwab ETFs are making inroads in the advisor market, albeit slowly. Two years ago, 38% of the ETF assets held by the company came from financial advisors. Today, that number is up to 48%. Several of the ETFs have reached their three-year anniversaries, providing the track record some advisors demand. And Chandoha says many advisors who’ve come on board believe that offering the lowest-cost pricing helps them fulfill their responsibility as fiduciaries.

Jonathan Citrin, CEO of the CitrinGroup in Birmingham, Mich., was cautious when he began using Schwab’s ETFs about three years ago. “I’m a bit allergic to proprietary products, and I would never decide to invest in them based solely on where my firm’s assets are custodied,” he says.

During the first 12 to 18 months after their introduction, Citrin used the ETFs sparingly as he monitored their expense ratios, bid-ask spreads, premiums and discounts, and benchmark tracking error. Once he was confident the ETFs checked out on all those fronts, he began transitioning most of his firm’s ETF positions from iShares, State Street and Vanguard to the Schwab ETFs. “Going with the firm that has the lowest expense ratios seemed like the right move to make as a fiduciary,” he says.

He considered the tax implications to taxable accounts before taking the plunge. In some cases, he could mitigate the hit through tax-loss harvesting. In others, he figured it would take several years before the lower costs associated with the Schwab ETFs would outweigh the tax bite from capital gains. Today, the firm has about one-third of its $60 million in assets in Schwab ETFs.

Ironically, he says, the only shortcoming is the lack of variety—Schwab’s secret sauce for keeping costs so low. For that reason, he uses other ETF providers for exposure to commodities, currencies and other alternative investment strategies. “I’d also consider using ETFs based on fundamental indexes if Schwab offered them,” he says.

Roger Wohlner, financial advisor with Asset Strategy Consultants in Arlington Heights, Ill., is less impressed with Schwab’s low expense ratios. “The ETFs I’m using are already very cheap, and I’m comfortable with them,” he says. “I’m not going to trade out of what I already own for a few basis points, especially in accounts where taxable gains are an issue.”

Still, the commission-free feature makes the Schwab funds good for using on a limited basis in smaller accounts, or situations where there may be a need for frequent rebalancing. And he hasn’t ruled out the possibility of using Schwab ETFs more frequently in the future, especially for new money. “They seem to be well constructed and representative of their indices and asset classes,” he says.