Global markets have entered the meltdown stage, accelerating in the past few days beyond a relatively orderly stock-market correction. With coronavirus cases now on all continents, this is no longer a domestic China problem; that suddenly dawned on complacent investors after last weekend’s big outbreak in Italy.

Hence the stampede to get into cash as lockdowns and states of emergency have multiplied, from Lombardy to Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido. Any attempt by the stock markets to bounce is just being seen as an opportunity to offload more shares. This is a catch-up effect and is starting to look overdone.

Yes, investors hate uncertainty and the deluge of virus warnings from businesses is alarming, but the markets are starting to price in a global recession and that doesn’t seem a true reflection—at least, not yet—of the virus’s impact. Largely, this is down to portfolio protection. It’s also a symptom of the longest-ever bull market for equities; a catalyst for a long overdue correction that has been delivered all at once. As my colleague Chris Hughes has noted, many of the biggest European companies have problems that predate the virus scares.

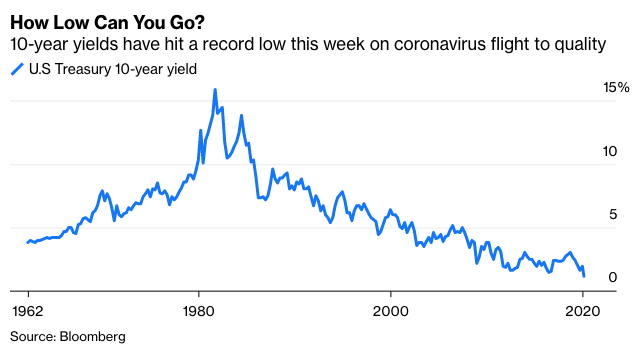

With an increasing amount of investments in passive index funds there’s a shoal effect. Re-weighting out of equities into the perceived safety of bonds is the knee-jerk reaction, even if yields are non-existent. It becomes a return of capital game (that is, putting it back somewhere safe) rather than return on capital. Poor corporate results are going to be punished more heavily in a febrile market environment.

The U.S. economy in particular is still in decent shape. The U.K. is readying for its biggest fiscal boost in history and there are even signs Germany has got the message. Noises out of the European Commission are that budgetary limits can be eased. China has managed the crisis steadily and Japan cannot be far away from pulling the stimulus lever again. Are you listening G20? That is where the concerted political and economic response needs to come from.

This is not a deadly killer like Ebola. Markets will eventually rationalize what’s going on, and accept that the world can get back to business—with sensible precautions. There will be a first-quarter hit to global growth, but it will hopefully be contained—so long as the virus is contained. Countries heavily dependent on tourism will suffer longer.

Fixed-income markets in particular have got ahead of themselves in driving toward all-time lows. This effectively signals recession, with a further three U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate cuts now being priced in for this year. So far the reaction from the Fed, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan is that none will be forthcoming.

This might change, of course, given the deep selloffs on Friday. But it’s right for central bankers to keep a calmer head than market traders. A token Fed cut—or at least a promise of ongoing liquidity provision—wouldn’t hurt in the short term. Christine Lagarde has said the ECB doesn’t need to take action yet, but again some restricted measure might help confidence.

This is both a demand and supply shock, given the strain it puts on global supply chains and on consumers and travelers. The reality is that there’s very little central banks can do to arrest it—bar some symbolic nod to improve sentiment. The Hong Kong government even tried helicopter money this week, without any discernible effect. Monetary policy is practically useless in this context. It’s down to governments to fire up the fiscal engines.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.