Howard Marks, the legendary credit investor and Oaktree Capital Management co-founder, has historically taken a humble approach to investing: the macro future is essentially unknowable, so active investors should focus on the small-picture things where they can gain an informational advantage. Here’s how he put it in his 2011 book The Most Important Thing:

I’m firmly convinced that (a) it’s hard to know what the macro future holds and (b) few people possess superior knowledge of these matters that can regularly be turned into an investing advantage.

Which is why I was so surprised—and initially disappointed—to see him put out a pair of essays recently that seemed to traffic in the sort of sweepy macro soothsaying that he’s long criticized. The essays— “Sea Change” and “Further Thoughts on Sea Change”—make splashy predictions about the slowing or reversal of globalization and the knock-on effects in the form of enduring inflationary pressures and, ultimately, higher interest rates. Here’s a brief bullet point summary of the two memos (which you can read in full here and here.)

• The Fed kept interest rates ultra-low for the better part of the decade after the financial crisis, and it was happy to leave them there as long as inflation didn’t materialize.

• Businesses got used to easy money; bonds and credit in all their forms underperformed; and equities and property did very well due to cheap funding and low discount rates.

• But now, everyone has realized that inflation is still a threat, so we shouldn’t expect the coming years to feature 2009-2022 interest-rate levels. Expect rates in the 2%-4% range, instead of 0%-2%.

• On balance, credit offers a better risk-reward than equities in that environment.

There’s clearly a bit to politely criticize here. Marks is indeed casting himself as the sort of macro fortune teller that he’s long told us didn’t exist (even if he’s at least self-aware about it), and he’s using those same macro forecasts to arrive at a somewhat self-serving conclusion (that credit markets—his firm’s area of expertise—are likely to be among the biggest beneficiaries.) But ultimately, I think Marks captures the nuance of a complex situation better than some of his contemporaries.

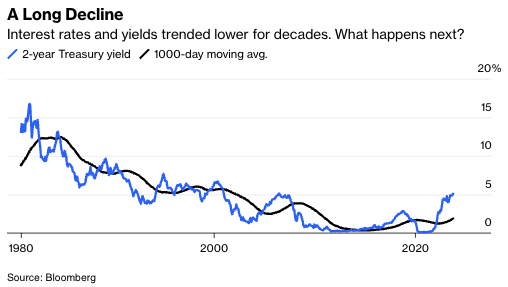

Marks is part of a growing field of investing personalities making bold claims about interest rates. Most of them start with the observation that borrowing costs declined consistently from the 1980s through the start of the pandemic and end with a warning about what the cessation of the trend could mean to the investment landscape.

It’s one thing to acknowledge that policy rates can’t go much lower than they got in the 2009-2022 period anytime soon. The Japanese experience notwithstanding, basic logic suggests that any downward trend must necessarily slow or end as it approaches zero. Beyond that, there’s significant room for disagreement on the degree of the upswing and its implications, and all of it is highly speculative.

First, consider the question of degree. Bill Ackman, the billionaire Pershing Square Capital Management founder, thinks that inflation may be moving permanently higher due to structural changes in the global economy, including (like Marks) deglobalization, but also the green energy transition and increased defense costs. As a result, he’s projecting that inflation could persistently run around 3%, which would mean policy rates of some 3.5% (my calculation, based on Ackman’s inflation forecast and his presumed real interest rate of 0.5% —This is also the longer-run real neutral rate implied by the median projection in the Fed's Summary of Economic Projections. Policymakers estimate nominal longer-run neutral to be 2.5% and longer-run inflation to be 2%, so it follows that they think that the neutral real rate of interest is 0.5%.). That, to me, is an extreme forecast that presupposes a lot will go wrong, and not much will go right. In the 20 years before 2021, year-on-year consumer price index inflation averaged just 2.1% and rarely detoured to the 3% level.

I can use the same facts to tell a much less concerning story about interest rates. In this more optimistic scenario, inflation will return to its old ways (around 2%) by late next year or early 2025, and policy rates will settle in around normal levels (about 2.5%) in the decade or so that follows. That will feel a bit high after the aberrations of the post-financial crisis period, and interest rates will cease to be a tailwind for equities and property. But they won’t be high enough to be a headwind.

Marks doesn’t really take a firm stand on the question of how high rates may be. In his first essay, he ventures an estimate of 2% to 4%—an enormous range that encompasses hawkish scenarios (Ackman) and relatively subdued ones (mine).

Next, there’s the question of the investment implications, and again it’s important to separate facts from speculation. Consider an influential—but also somewhat melodramatic—paper from Federal Reserve researcher Michael Smolyansky, “End of an era: The coming long-run slowdown in corporate profit growth and stock returns.” As Smolyansky showed in his paper, much of the S&P 500 Index’s returns in the 1989-2019 period can be attributed to declining interest rates, either through the corporate profits channel (lower borrowing costs) or valuations (lower “risk-free” rates caused price-earnings multiples to expand.) These are empirical truths that one can’t argue with. The speculation comes when he implies—starting with the title—that the end of the interest-rate tailwind must necessarily translate into slower profits and equity returns going forward.

Again, here, I can tell a positive story using the same set of facts. U.S. and global productivity growth, for instance, were the special sauce behind many enduring bull markets before the 1980s, and there are compelling reasons to think that developments in artificial intelligence could bring about just such a productivity boost in the coming years. Recent research from Bank of America Corp. projected that 75% of the companies they cover will see a positive financial impact from AI in the next five years, with a median operating margin improvement of 250 basis points for the companies in the S&P 500.

Consider, for instance, the period from the end of World War II to the early 1970s—a time sometimes known as the golden age of productivity growth and which coincided with the adoption, among other things, of the jet engine in commercial aircraft and vast improvements in the time it took to ship people and freight. Generally speaking, it was an era of rising interest rates, but nevertheless a good time to be invested in the stock market. I certainly can’t guarantee that this will happen again, but nor can the bears assure us that it won’t. There would be a steep opportunity cost to missing a productivity-driven rally.

Ultimately, Marks seems to be with me on the uncertainty around all of this, which comes through in the wide range of potential outcomes he addresses. As he said in Part I (on Dec. 13), “Oaktree’s investment philosophy doesn’t prohibit having opinions, just acting as if they’re right.” I don’t read his call to boost credit allocations as a high-conviction prediction about the macro future, but rather as an assessment of relative risk and reward given where pricing stands at the current moment. Here’s the key bit (from Part II on Oct. 11; emphasis his):

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index has returned just over 10% per year for almost a century, and everyone’s very happy (10% a year for 100 years turns $1 into almost $14,000). Nowadays, the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Constrained Index offers a yield of over 8.5%, the CS Leveraged Loan Index offers roughly 10.0%, and private loans offer considerably more. In other words, expected pre-tax yields from non-investment grade debt investments now approach or exceed the historical returns from equity.

And, importantly, these are contractual returns.

Another classic Howard Marks line (from The Most Important Thing) is: “While we never know where we’re going, we ought to know where we are.” And Marks, of all people, knows an attractive yield when he sees one. If the U.S. enters a deep recession, of course, defaults could pile up, but equities would get clobbered in that scenario as well. Nothing in life is guaranteed, but the “contractual returns” of high-yield sure look like more of a lock than stocks.

Regular readers of this column know that I have a visceral negative reaction to anyone forecasting that “everything’s changing forever.” Much in the same way that the stock market has predicted nine of the past five recessions—to cite an old joke from the late economist Paul Samuelson—market commentators tend to predict vastly more fundamental shifts than actually occur. When they get them right, it’s often for the wrong reasons. I got this way from reading Marks, so naturally, I was taken aback when I saw the title of his first essay, “Sea Change.”

But we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover—or a markets memo by its title—and the “Sea Change” mini-series is ultimately still the same old Howard Marks. Everyone’s making big macro calls these days, and he couldn’t help himself either—but at least he still has the sense to recognize the uncertainty around the projection. The point is, the interest rate environment is in an unusual place at the moment, and the range of possible outcomes is wide. So while the Ackman scenario (3% inflation for the foreseeable future) is still highly unlikely, credit at current yields may just be the better place to camp out as an unknowable future plays itself out.

Jonathan Levin is a columnist focused on U.S. markets and economics. Previously, he worked as a Bloomberg journalist in the U.S., Brazil and Mexico. He is a CFA charterholder.