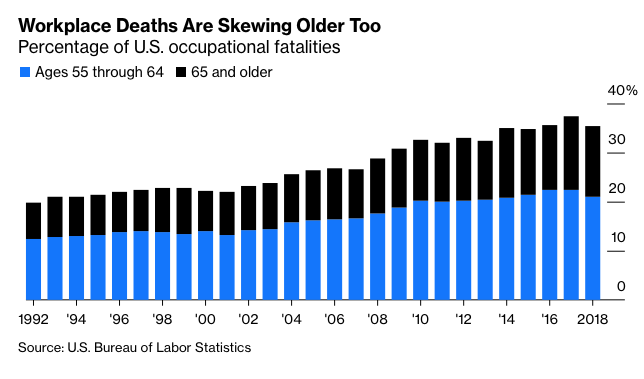

In any case, as the share of older workers has grown, the share of workplace deaths that they account for has grown, too.

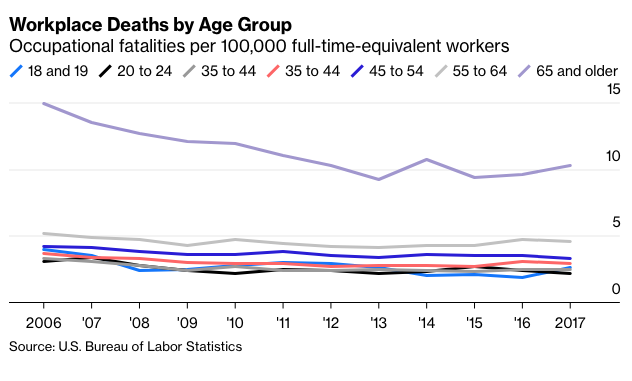

It’s not that the workplace has been getting more dangerous over time for older workers. Every age group has seen declines in workplace fatality rates since 2006, and the decline for those 65 and older has been the biggest. But 65-plussers’ share of the workforce has grown by three percentage points just since 2006, and their occupational fatality rate remains much, much higher than anybody else’s: 10.3 in 2018 versus 3.5 for the workforce overall and 4.6 for those ages 55 through 64.

Being older obviously does make one more prone to keel over, but the occupational fatality statistics don’t include on-the-job deaths due to natural causes. So what explains the higher death rates of older workers? In an analysis published last month that was the inspiration for this column, BLS economists Sean M. Smith and Stephen M. Pegula sliced and diced the numbers in several ways in an attempt to answer that question. (To get statistically meaningful results, they generally focused on the entire 55-plus age group, not the smaller but much-higher-risk group of workers 65 and older, and combined data for a number of years.)

One thing that they found was that those 55 and older were more likely than younger workers to die of lingering injuries days, weeks, months or even years after a workplace incident. Older people are more fragile than younger ones, so they have more trouble recovering from workplace injuries than their younger peers, and are more likely to suffer certain injuries (hip fractures, for example).

When it comes to kinds of accidents, the biggest cause of workplace fatalities for both older and younger workers is roadway incidents involving motorized land vehicles, aka traffic accidents, which Smith and Pegula found were responsible for about a quarter of deaths from 2011 through 2017 among those under 55 and among those 55 and older—so no disparity there. Fatalities among those 55 and older were significantly less likely to be caused by electrocution, homicide and suicide than among younger workers, while deaths from being struck by an object or equipment, falling to a lower level and being hit by a vehicle as a pedestrian made up a moderately larger share of workplace deaths for older workers than younger ones. The cause of death for which the age difference was the biggest was nonroadway noncollision incidents, which accounted for 6% of workplace deaths for those 55 and older and 3% for those 54 and younger.

What could these nonroadway noncollision incidents possibly involve? Think tractors. Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting had the second-highest fatality rate in 2018 of any industry whose fatality rate was estimated by the BLS, after truck transportation (23 deaths per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers versus 28). Smith and Pegula found that, from 2003 through 2017, farmers, ranchers and other agricultural managers suffered 14% of the occupational fatalities among those 55 and older, versus a bit more than 2% among those 54 and younger.

For a variety of reasons, farmers have been finding it harder and harder to retire—or easier and easier not to retire, as modern farm equipment allows them to do more on their own. Farmers and ranchers have the highest median age among occupations for which the BLS calculates that figure, at 56.1 years (the agency doesn't calculate a median age for legislators, but from the information it does provide it is clear that this would be even higher than that of farmers), and a remarkable 30.8% of them are 65 and older. Most of the fatal nonroadway noncollision incidents mentioned above involved jack-knifed or overturned vehicles, so basically, a not-insignificant number of elderly farmers are dying when their tractors or pickup trucks tip over. But hey, they’re out in the fields, amid the amber waves of grain. There are worse ways to go.

Which brings us to the bigger question of whether anything should be done about this rise in older-worker fatalities. Smith and Pegula conclude their study with the hope that it will help safety and health experts “tailor their efforts to best meet the needs of older workers and to keep them safe during their careers,” which sounds like a good plan but not exactly a game-changer. Technological advances have played a big role in reducing workplace risks in the past, and one can easily see how self-driving technology could make truck driving, farming and other occupations much safer—albeit at the same time destroying lots of jobs. In the meantime, the most powerful policy lever seems to be retirement-system design.