Even for a market veteran like John Miller, managing director and co-head of fixed income at Nuveen Asset Management, it’s hard to remember a time when so many balls have been in the air. “There are more potentially impactful events and issues to watch for now than I’ve seen in my 24-year career in the municipal market,” he observes.

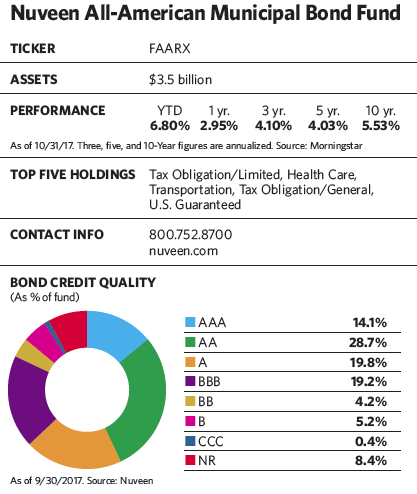

Yet municipal bonds have proved to be extraordinarily resilient this year, performing better than many other corners of the fixed-income markets. As of September 30, the broad municipal bond market was up 4.66% year to date, well above the 3% return for the taxable U.S. aggregate bond market. High-yield municipals fared even better, rising 7.22% over the period. Without beleaguered Puerto Rico bonds weighing it down, the latter group would have risen 10.35% over the period.

Much of that performance is attributable to a bounce-back from a late 2016 downturn, when investors believed the newly elected president would lower tax rates, destroy the Affordable Care Act and make other moves that could hurt munis. As 2017 has progressed, investors are coming to realize that the strongly divided Congress and unpredictable leadership could water down those changes—if they happen at all.

“Even if some of Trump’s goals are accomplished, the negatives for municipal bonds are not likely to be as bad as many people originally thought they would be,” says Miller.

One of the biggest questions hovering over the market now is the prospect for lower individual and corporate tax rates, which could hurt municipal bonds by making their tax-exempt status less attractive. Miller points out that, historically, the relationship between tax rate changes and municipal bond prices is far from solid. During the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, when taxes were cut, municipals still produced healthy gains. Conversely, the increase in taxes under former President Obama did not benefit municipal bonds.

What’s more, the current proposed Republican tax plan isn’t as onerous as it might appear at first glance. Because it would not lower the top personal income tax rate much below the current rate of 39.6%, any change would not likely have much effect on demand for tax-exempt bonds. Additionally, Miller says the 3.8% Medicare surtax on investment income for high earners, which doesn’t apply to municipal bond income, “will likely stick around.” And while the Republican tax plan would also eliminate all itemized deductions except those for mortgage interest and charitable contributions, it does not take aim at the tax exemption of municipal bond interest.

While the personal income tax rate would not decline significantly, the corporate tax rate would fall from 35% to 20% under the Trump proposal. That change could lead to a reduction in demand for municipal bonds from banks and insurance companies.

Ultimately, says Miller, legislators are more likely to settle on a corporate tax rate in the 25% to 30% range. While a lower corporate tax rate might make municipals less attractive to some companies, “it’s unlikely that they would sell off a well-performing municipal bond portfolio because of it,” he says. “The most important thing is that municipals stay tax-exempt, which is the case in the initial tax plan.”

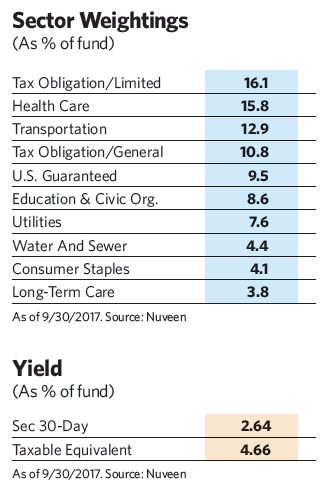

The elimination of the deduction for state and local taxes, another possibility under the proposal, would make bonds that are exempt from state taxation more attractive for investors in high-tax states. For a taxpayer subject to California’s 11.3% tax rate (if the federal rate were 35%), eliminating the deduction would increase the taxable-equivalent yield of a 2.00% California-exempt bond from 3.47% to 3.72%. Over the last year, natural catastrophes and political upheaval have brought a barrage of woes to the municipal bond market. A hurricane that brought widespread devastation to Puerto Rico made many wonder whether the U.S. jurisdiction would ever be able to pay off its bonds. President Trump’s mission to destroy the Affordable Care Act, threatening coverage for millions of people, brought uncertainty to hospital revenue bonds. And efforts to lower individual income tax rates, if successful, threaten to make the tax-free status of municipal bonds less attractive.

Over the last year, natural catastrophes and political upheaval have brought a barrage of woes to the municipal bond market. A hurricane that brought widespread devastation to Puerto Rico made many wonder whether the U.S. jurisdiction would ever be able to pay off its bonds. President Trump’s mission to destroy the Affordable Care Act, threatening coverage for millions of people, brought uncertainty to hospital revenue bonds. And efforts to lower individual income tax rates, if successful, threaten to make the tax-free status of municipal bonds less attractive.

Municipal Bonds Hang Tough

December 1, 2017

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment