In 2016, the U.S. economy navigated some difficult challenges including low oil prices, a strong dollar, tightening financial conditions, and the threat of deflation. As we turn the calendar to 2017, concerns have shifted. Oil prices have stabilized; while the dollar, despite receiving a post-election boost, is unlikely to create the kinds of headwinds it created over the last three years. Increased anxiety over deflation in 2015 and early 2016 has flipped to “reflation” concerns. Conversations about fiscal austerity, through mechanisms like budget sequestration that left the economy relying on monetary stimulus through the Federal Reserve (Fed), have turned to a drum beat for fiscal stimulus through tax reform and infrastructure spending while the Fed slowly normalizes monetary policy. We have even started to see steadying in the manufacturing sector, following contraction under the influence of low oil prices, a strong dollar, and weaker global growth. Although the economy remains more fragile than during most prior expansions, these turning points have marked the economy’s ability to navigate a challenging period.

MOMENTUM SHIFTS

Taking into account all of these milestones, we believe the economic recovery that began in mid-2009 will likely pass its eighth birthday in 2017, as leading economic indicators continue to suggest low odds of a recession starting next year. However, the risk of a recession due to a policy mistake has risen over the course of 2016. The pro-growth policies likely to be enacted in the first half of 2017 by Trump, including corporate and personal tax cuts, increased spending on infrastructure and defense, and deregulation, may help to boost economic growth in 2017 and 2018 and increase the economy’s potential growth rate (while changing the mix of growth drivers). However, they may also lead to some of the “overs” that tend to emerge at the end of expansions (overconfidence, overborrowing, overspending), naturally accelerating the economic cycle and bringing a recession sooner than otherwise might have been the case.

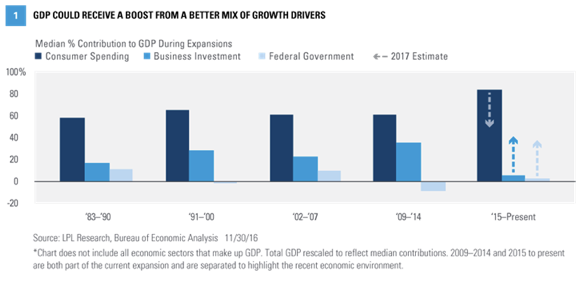

Focusing on 2017, between the economic momentum that started in late 2016, the boost from fiscal policy likely to be enacted by mid-2017, and a more business-friendly regulatory environment, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth may accelerate to a range closer to 2.5% in 2017, after spending most of the first seven-plus years of the expansion averaging just over 2.1%. The boost in 2017 comes as the main drivers of growth shift from an emphasis on the consumer to a mix that includes manufacturing, capital expenditures, and government spending [Figure 1]. Potential contribution from trade (net exports) remains a wild card, as the Trump administration’s trade policies, while attempting to shift the balance of exports and imports, may have a dampening impact on long-term trade growth. In addition, the deficit could make a comeback as a key economic topic for markets and policymakers in the aftermath of a potential shift to fiscal stimulus through lower taxes and increased infrastructure and military spending.

Of course, new risks could be around the corner. The Fed may start raising rates in earnest, if slowly, after a one-year hiatus between December 2015 and December 2016. Raising rates at this stage would simply reflect an improving economy, but finding the proper pace for rate increases will be a challenge. President-elect Donald Trump has expressed intentions to renegotiate trade agreements, but will face the challenge of improving them without starting a harmful trade war. And although fiscal stimulus may give a boost to growth, long-term challenges for the federal debt and budget deficit loom in the background.

PATH TO NORMALIZATION

Federal Reserve Is Fueling Up

At the start of 2016, the disconnect between the Federal Reserve and the federal funds futures market about the anticipated future direction of monetary policy was striking. The Fed, which had just initiated its first tightening cycle in more than 11 years in December 2015, anticipated raising rates by 200 basis points (2.0%)* over the course of 2016 and 2017, which would put the fed funds target rate at around 2.375% by the end of 2017. Meanwhile, the market was pricing in just four 25 basis point hikes over the course of 2016 and 2017, putting the fed funds target rate at just 1.375% by year-end 2017. The 100 basis point disparity, the equivalent of four 25 basis point rate hikes, was so wide that it led to a number of destabilizing global imbalances in the first few months of 2016, which in turn contributed to the financial market turmoil over the first six weeks of the year.

As of late 2016, the Fed has raised rates just once more, at its final meeting of the year in December, leaving the fed funds target rate at about 0.625%. If its outlook for the economy, labor market, and inflation is met, the Fed said it would raise rates 75 basis points in 2017 and 75 basis points in 2018, leaving the fed funds target rate 2.125% at the end of 2018. Meanwhile, the market now sees roughly two hikes in 2017 and two in 2018, putting the fed funds target rate around 1.825% at year-end 2018. At around 25 basis points, the disagreement on the path of rates over the next two years is likely to prove much more manageable for global markets to absorb than the 100 basis point gap at the start of 2016.

Our view is that we may meet the Fed’s forecasts for the economy, labor market, and inflation in 2017, leading the Fed to raise rates twice during the year. The economy might receive a boost from fiscal stimulus, which can lead to a virtuous cycle of added confidence and the release of what economists colorfully refer to as the economy’s “animal spirits,” where greater confidence leads to increased activity. If this happens, it will push GDP growth above its currently muted potential, tighten resources, increase labor costs, and ultimately drive inflation. Given this possibility, our estimate of two rate hikes has an upward bias with three hikes more likely than one, especially if inflation moves above 2.0% and remains there, as we expect.

*Basis points (bps) refer to a common unit of measure for interest rates and other percentages in finance. One basis point is equal to 1/100th of 1%, or 0.01%, and is used to denote the percentage change in a financial instrument.