This begs the question who to listen to, to cut through the noise. The general view of Fed insiders is that the Fed Governors dictate the tone, supported by their staff economists. These are not to be mistaken with the regional Federal Reserve Presidents that may add a lot to the discussion, but are less influential in the actual setting of policy. Zooming in on the Fed Governors, Janet Yellen as Chair is clearly important. If one takes Vice Chair Fischer out of the picture, though, there is currently only one other Ph.D. economist, namely Lael Brainard; the other Governors are lawyers. Lawyers, in our humble opinion, may have strong views on financial regulation, but when it comes to setting interest rates, will likely be charmed by the Chair and fancy presentations of her staff. I single out Lael Brainard, who hasn't received all that much public attention, but has in recent months been an advocate of the Fed's far more cautious (read: dovish) stance. Differently said, we believe that after telling markets last fall how the Fed has to be early in raising rates, Janet Yellen has made a U-turn, a policy shift supported by a close confidant, Brainard, but opposed by Fischer, who is too much of a gentleman to dissent in public.

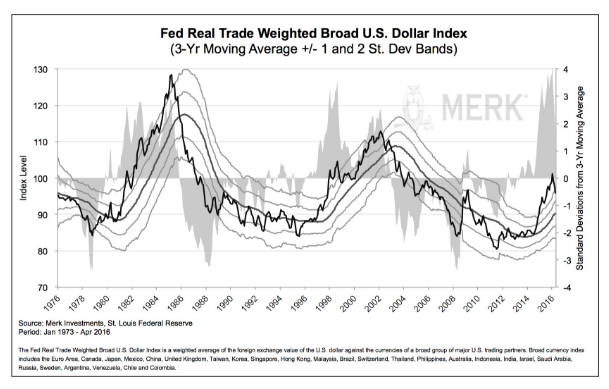

It seems the reason anyone speaks on monetary policy is to shape expectations. Following our logic, those that influence expectations on interest rates, influence the value of the dollar, amongst others. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke decided to take this concept to a new level by introducing so-called "forward guidance" in the name of "transparency." I put these terms in quotation marks because, in my humble opinion, great skepticism is warranted. It surely would be nice to get appropriate forward guidance and transparency, but I allege that's not what we have received. Instead, our analysis shows that Bernanke, Yellen, Draghi and others use communication to coerce market expectations. If the person with the bazooka tells you he (or she) is willing to use it, you pay attention. And until not long ago, we have been told that the U.S. will pursue an "exit" while rates elsewhere continue lower. Below you see the result of this: the trade weighted dollar index about two standard deviation above its moving average, only recently coming back from what we believe were extremes:

If reality doesn't catch up with the storyline, i.e. if U.S. rates don't "normalize," or if the rest of the world doesn't lower rates much further, we believe odds are high that the U.S. dollar may well have seen its peak. Incidentally, Sweden recently announced it will be reducing its monthly bond purchases (QE); and Draghi indicated rates may not go any lower. While Draghi, like most central bankers, hedges his bets and has since indicated that rates might go lower under certain conditions after all, we believe he has clearly shifted from trying to debase the euro to bolstering the banking system (in our analysis, the latest round of measures in the Eurozone cut the funding cost of banks approximately in half).

On a somewhat related note, it was most curious to us how the Fed and ECB looked at what in some ways were similar data, but came to opposite conclusions as it relates to energy prices. The Fed, like most central banks, like to exclude energy prices from their decision process because any changes tend to be 'transitory.' With that they don't mean that they will revert, but that any impact they have on inflation will be a one off event. Say the price of oil drops from $100 to $40 a barrel in a year, but then stays at $40 a barrel. While there's a disinflationary impact the first year, that effect is transitory, as in the second year, inflation indices are no longer influenced by the previous drop.

The ECB, in contrast, raised alarm bells, warning about "second round effects." They expressed concern that lower energy prices are a symptom of broader disinflationary pressures that may well lead to deflation. We are often told deflation is bad, but rarely told why. Let's just say that to a government in debt, deflation is bad, as the real value of the debt increases and gets more difficult to manage. If, in contrast, you are a saver, your purchasing power increases with deflation. My take: the interests of a government in debt are not aligned with those of its people.

Incidentally, we believe the Fed's and ECB's views on the impact of energy prices is converging: we believe the Fed is more concerned, whereas the ECB less concerned about lower energy prices. This again may reduce the expectations on divergent policies.

None of this has stopped Mr. Draghi telling us that US and Eurozone policies are diverging. After all, playing the expectations game comes at little immediate cost, but some potential benefit. The long-term cost, of course, is credibility. That would take us to the Bank of Japan, but that goes beyond the scope of today's analysis.

To expand on the discussion, please register for our upcoming Webinar entitled 'What's next for the dollar, currencies & gold' on Tuesday, May 24, to continue the discussion. Also make sure you subscribe to our free Merk Insights, if you haven't already done so, and follow me at twitter.com/AxelMerk. If you believe this analysis might be of value to your friends, please share it with them.

Axel Merk is president and chief investment officer of Merk Investments.