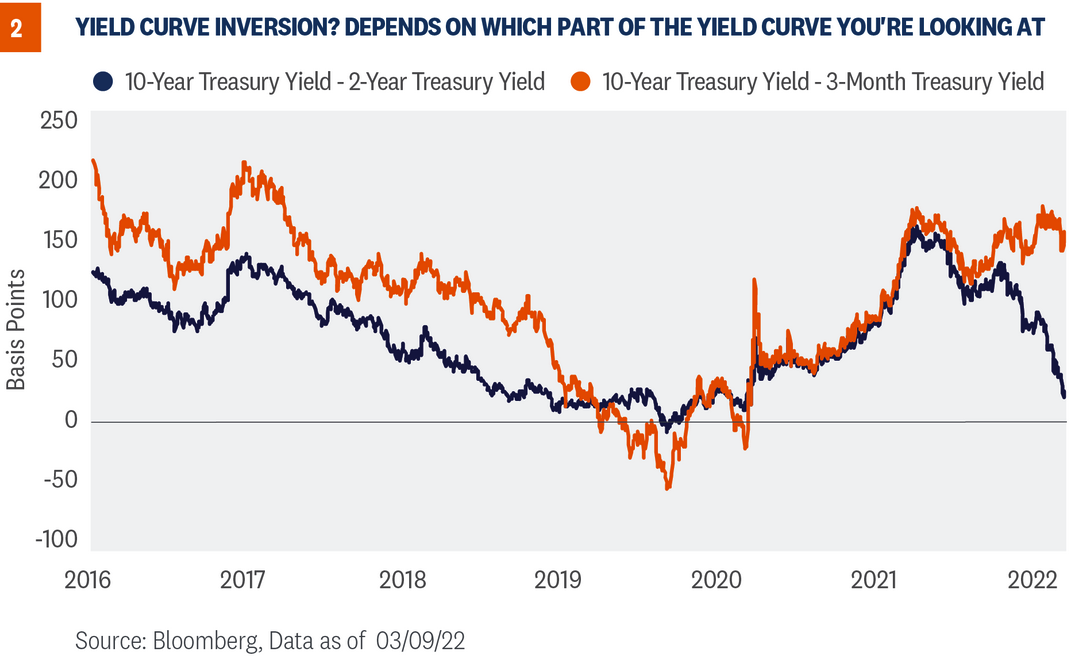

The Federal Reserve is widely expected to increase short-term interest rates this week for the first time since emergency levels of monetary support were enacted in the aftermath of the Covid-19 shutdowns. With its asset purchase programs fully winding down last week (the Fed was buying $120 billion a month of U.S. Treasury and mortgage securities), the Fed has signaled that it is ready to take the next step towards policy normalization and is set to start a series of interest rate hikes over the coming years. How many rate hikes and how quickly the Fed gets back to a neutral policy rate—the interest rate that neither stimulates nor restrains economic growth—is still uncertain. As seen in Figure 1, markets expect the Fed to raise interest rates at least six times this year, which would bring the policy rate to between 1.50% and 1.75%. It should be noted that these market-implied expectations are volatile and expectations can and do change over time.

Our view remains that Fed interest rate hikes will likely begin this week with a 25 basis point (0.25%) increase and then three to four more rate hikes at subsequent meetings in 2022. Moreover, we think the Fed will start to reduce its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet in the second half of 2022. There is a risk to the upside (in hikes) depending on the trajectory of inflationary pressures. If consumer price pressures moderate over the course of the year as we and the Fed expect, then we think the Fed can take a more gradual approach to interest rate hikes. However, if inflationary pressures remain stubbornly high and we start to see longer-term inflation expectations become unanchored (more on this below), the Fed may be forced to move more aggressively than what is even already priced in.

The Committee will also release individual meeting participants’ projections for real gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the unemployment rate, and inflation for the next several years, as well as its longer-term forecasts. It’s largely expected that the Fed will confirm that we are near/at full employment and that the strong labor market can handle a series of interest rate hikes. The Fed will also likely adjust its forecast for GDP growth down (from December’s forecast of 4.0% GDP growth in 2022) and its forecasts for inflation up (with PCE headline and core metrics, their preferred inflation measures, at 2.6% and 2.7% back in December). However, the Committee will likely maintain its stance that inflation will fall back to its longer-term trend in 2023.

Has The Fed Lost Control Of The Inflation Narrative?

Geopolitics Add Uncertainty To Policy Normalization

That said, while we think the Fed will be less hawkish than it otherwise would be due to the ongoing conflict in Eastern Europe, price stability is one of its primary mandates. So, as long as inflation pressures remain above the Fed’s inflation target, we think the Fed will continue along the path of policy normalization.

Will Fed Rate Hikes Invert The Yield Curve?

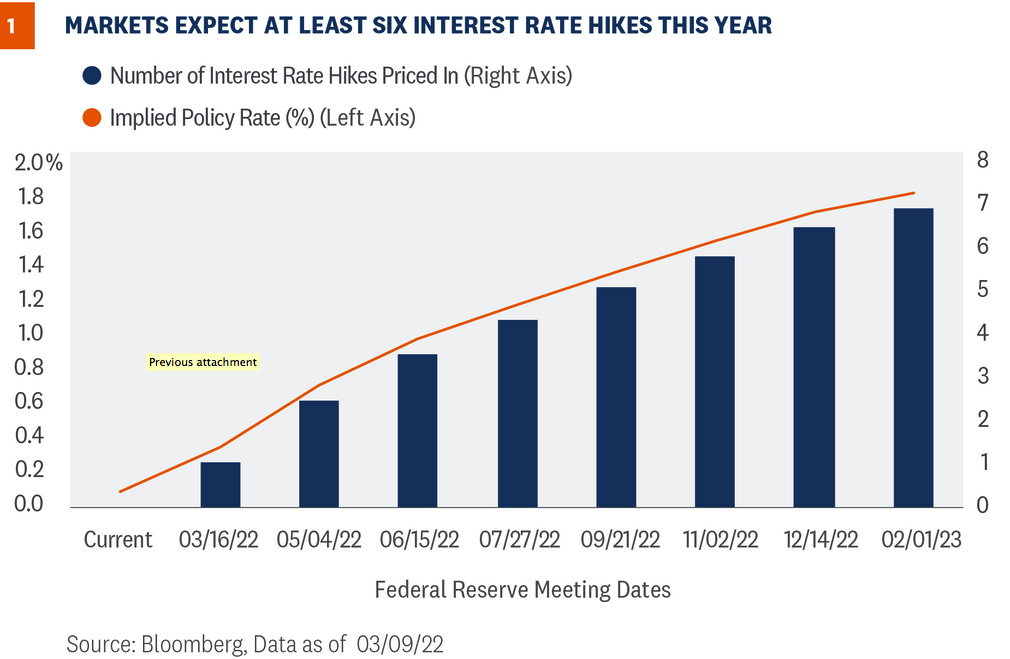

The Fed’s ability to substantially raise interest rates before yield curve inversion has been trending lower over the last few decades. Because the 10-year Treasury yield has been in a secular decline since the mid-80s, the Fed’s ability to raise short-term has been constrained. That said, we’re likely to hear more in the coming months about yield curve inversion and, thus, increased recessionary risks. And while it’s true that the Fed has never started a rate hiking campaign when the yield curve has been this flat (as seen in Figure 2 as measured by the difference in yields between 10-year and 2-year U.S. Treasury), the more important tenors on the yield curve, at least in terms of presaging recessions, are the three-month and 10-year yields, which are still far from inversion. As such, we believe the Fed has room to raise interest rates before true inversion takes place.

Inflation expectations are informative about how the current inflation experience has shaped the public’s views regarding future inflation. And the Fed pays close attention to how these expectations change over time. De-anchored inflation expectations tend to make further inflationary pressures self-fulfilling. So, it’s notable that the Fed’s January Survey of Consumer Expectations (the most recent one available) showed a decrease in short and medium-term inflation expectations. While still elevated, falling consumer expectations about future consumer price increases is encouraging. Moreover, longer-term market-implied inflation expectations are in line with historical averages. It seems that, despite the elevated inflation readings we’ve seen over the past few months, markets and consumers still expect price pressures to abate, which could allow the Fed to take a more moderate approach to interest rate hikes.

Complicating the expected path of policy normalization, however, is the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. As sanctions and boycotts continue against Russia, which is the world’s third largest oil producer, we may see continued upward pressure on commodity prices, on top of the inflation effects already in place from Covid-19-related supply chain disruptions. Additionally, Ukraine and Russia together account for more than a quarter of global trade of wheat. The conflict has closed major ports in Ukraine and severed logistics and transport links. As such, the negative impact to global trade, both energy and ex-energy, are likely to weigh on the prospects for global economic growth, at least in the near term. This heightened uncertainty and potential shock to financial and economic growth trajectories further complicate the Fed’s ability to aggressively raise short-term interest rates.

One of the big risks associated with Fed rate hikes, though, is when the Fed funds rate is pushed higher than longer-term Treasury yields. In this instance, the yield curve becomes inverted, which means shorter maturity securities out-yield longer maturity securities. Generally, the opposite is true and the yield curve is upward sloping. The slope of the yield curve is an important economic gauge, as an inverted yield curve has presaged every recession since the 1970s (though not all inverted yield curves have been followed shortly by recessions).