The Rebalancing Bonus

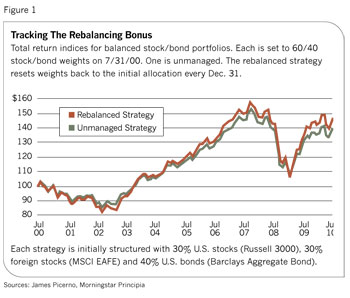

A hands-off approach to asset allocation might come at a price. Consider how a simple 60%/40% asset allocation of stocks and bonds fared over the ten years through this past July when it was rebalanced-and when it wasn't (Chart 1). The 60% equity weight is evenly split between U.S. stocks (represented by the Russell 3000) and foreign stocks (represented by the MSCI EAFE). The fixed-income portion is represented by the Barclays Capital Aggregate Bond index.

One strategy starts with the 60/40 mix and lets it run untouched over ten years. The other portfolio is identical in the beginning except that it's rebalanced back to the original 60/40 allocation every December 31. As Figure 1 shows, the rebalanced portfolio earned roughly 50 basis points a year more than its unmanaged counterpart for the decade: 3.9% versus 3.4%, based on annualized total returns.

Is a rebalancing bonus unusual? Not really. Several studies report that keeping asset allocation in a portfolio within a range in the long run tends to offer slightly better returns than when the same portfolio is allowed to drift. Does rebalancing guarantee superior results? No, although the same caveat's true for all strategies. But the odds are that you'll see better performance over time by rebalancing a multi-asset class portfolio than you would by leaving the same portfolio untended. As for how much better, several strategists guesstimate that you could make 50 to 100 basis points more. Figure 1 seems to support that view. One ten-year stretch doesn't mean much, but similar results over different periods have been documented as well.

"The actual return of a rebalanced portfolio usually exceeds the expected return calculated from the weighted sum of the component expected returns," wrote financial planner William Bernstein in a 1996 study, The Rebalancing Bonus (available at Efficientfrontier.com). In other words, rebalancing generally boosts return for a broadly diversified asset allocation over the long haul.

The technical reason is that broad asset class returns have a history of mean reversion. Stock market performance, for instance, tends to cycle around an average with an upward bias.

Does a higher return from naive rebalancing qualify as alpha? Yes, says William Reichenstein, a professor of finance at Baylor University. Rebalancing can add or subtract value, he says. Ultimately, it's a contrarian strategy, he explains. Asset classes and individual securities go in and out of favor, so "you'll get a positive alpha if mean reversion helps."

But some strategists think the return difference is linked to a particular flavor of risk. "If you can write the rule down and tell a machine to execute it, it's beta," says Larry Siegel, the former director of investment research at the Ford Foundation who is now an advisor to Ounavarra Capital in New York. By Siegel's standard, a conventional rebalancing strategy that generates a return premium is still beta. But it's a beta with a bigger helping of risk-a risk tied to the fluctuation in expected return born of mean reversion.

Rebalancing And Redesigning Indices

The effects of rebalancing can also be found in alternative index designs. One example is the equally weighted version of the S&P 500, which has a history of beating its better-known, cap-weighted counterpart. The S&P 500 Equal Weight Index (S&P EWI), which is rebalanced quarterly to maintain an even balance among securities, has gained 6% a year for the decade through this past July. That's impressive considering that the conventional cap-weighted S&P 500 logged an annualized 0.8% loss. (Like other cap-weighted benchmarks, the regular S&P 500 index isn't rebalanced.)

Real-world portfolios have also gained an edge by equal weighting. The Rydex S&P Equal Weight ETF (RSP) reports a 1.2% annualized total return for the five years through this past July, according to Morningstar Principia. That compares with a roughly 0.3% annualized retreat for the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), which tracks the standard S&P 500.