And, of course, you may be wrong in your tactical decisions, says Byron Green of Green Investment Management, which blends tactical and strategic asset allocation disciplines in client portfolios. And even if TAA adds value, it won't come easily if you remain broadly invested, he adds. The more diversified a portfolio, the more difficult it will be to boost the return. That can lead an active investor to make bigger tactical bets in his attempts to beat a broad asset allocation benchmark, Green says. On the other hand, the investor can also lag the unmanaged benchmark if those bets go wrong.

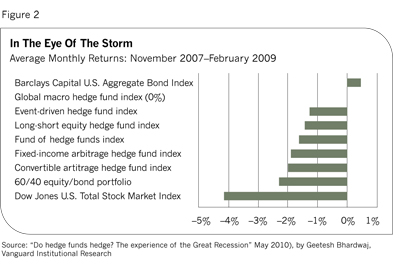

The financial crisis suggests that we should keep our expectations about active management modest. During the 15-month stretch through February 2009-one of the worst periods in the modern history of capital markets-several leading hedge fund categories suffered along with the stock market, according to a study by Vanguard (see Figure 2). To be fair, the stock market fared worse, and global macro funds as a group excelled at minimizing the losses.

But a simple 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds would have softened the blow too. "Most of the hedge fund categories failed to provide significant diversification beyond that of a 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds," the study concludes. So it's debatable whether clever hedge fund managers added any value over the naïve strategies from the old finance. Some did, but many didn't.

Superior Risk Management

Advisors not only chase higher return with these strategies but also hope to curb the threat of devastating loss. TAA can do that, but so can a dedicated portfolio-protection overlay. Yet not all protection strategies are created equal, warns Jerry McCollis, chief investment officer at Brinton Eaton, a wealth management firm in Madison, N.J.

For instance, it's easy to buy a put option on the S&P 500. If the market tanks, the put's price will soar, offsetting some or all of the associated loss. The problem is that when the stock market recovers, the put's value plummets. And the protection is costly over time, says McCollis.

"We're still looking for the ideal answer, but we found something close enough to put clients into," he continues. McCollis points to structured notes issued by Deutsche Bank based on the firm's Emerald Index, which fluctuates with the spread between daily and weekly volatility for the S&P 500 (customized notes based on the Emerald Index can also be tied to other market indices). The note generates a small profit when daily equity volatility is higher than its weekly counterpart, which is the trend over time. The risk management kicks in if daily volatility surges-as it usually does during market crashes. In that case, the note's value rises sharply, helping offset losses in stocks.

What's the risk? A sustained move in the same direction by equities at some point would boost weekly volatility over daily levels, triggering a loss for the note, perhaps a steep one. That's considered unlikely, but not impossible. Another danger is counterparty risk-institutions are taking the other side of the trade of this volatility swap and if they go bankrupt the notes could suffer big losses, perhaps to the point of becoming worthless. Otherwise, the note is expected to generate a small amount of income over time as long as weekly volatility remains under daily readings. That trend pays the expenses and perhaps dispenses a small amount of income over the long haul.

Meanwhile, McCollis is reluctant to say that modern portfolio theory failed or that traditional asset allocation no longer works. "It still does well what it was designed to do," he emphasizes-providing risk management over the long haul while delivering a reasonable return. But conventional asset allocation in late 2008 suffered a blow that it wasn't designed to withstand. The limitation suggests looking elsewhere to smooth over diversification's rough edges. Is the Emerald Index solution an answer? So far, so good, McCollis reports.

Maybe Wall Street's financial engineering has its advantages after all. But the core lesson in the old finance still applies: Risk and return are closely linked. Yes, the new finance tells us that risk is multidimensional and that asset allocation should be tailored and, to some degree, actively managed. That's a big change from the old finance, which saw broad, unmanaged market beta as the primary risk factor.