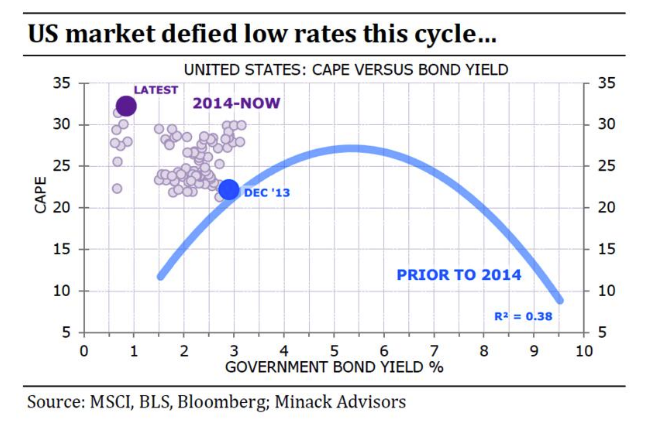

What is intriguing is the way the U.S. relationship between yields and earnings multiples has started to differ from its historic pattern in the last six years. Up to the end of 2013, there was a much more discernible correlation, with an R-squared of 0.38. Since the end of 2013, however, earnings multiples have been without exception higher than the previous relationship with interest rates would have suggested. They have never been further away. To be clear, this means that they now look unambiguously expensive, given where interest rates are, even though interest rates are so low:

From this we can learn two things. One is that the relationship between rates and earnings multiples seems to have changed at some point early in the last decade in the U.S., presumably when investors got used to the notion of enduring “lower for longer” rates coupled with low inflation. I would argue that this was because they believed the traditional relationship between rates and the economy had broken down. The second is that whatever is driving multiples higher, it isn’t rates. As the chart shows clearly enough, rates have been on or about where they are now for nine months. Earnings have dipped and then recovered, and this is the most expensive that stocks have been.

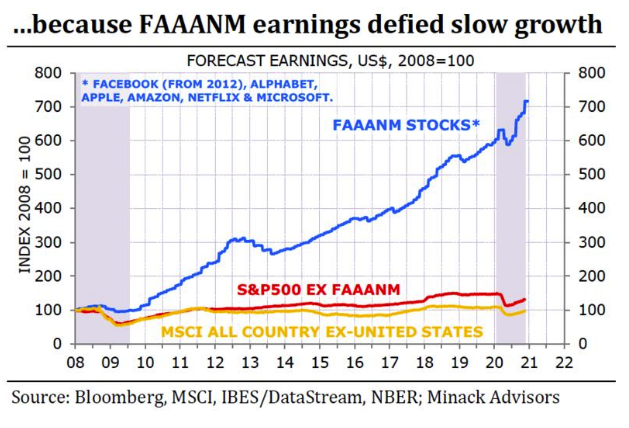

To find out what is driving multiples, Minack turns to the FANG stocks, which he defines as the FAAANMs (for Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Alphabet Inc., Netflix Inc. and Microsoft Corp.). The key point is that their earnings, until now, have defied slow growth that bedeviled the developed world during the post-crisis decade, and have even defied the slump that followed the Covid shock. The rest of the S&P 500, and indeed the rest of the world, did nothing remotely similar. The following chart from Minack shows the internet platform groups’ earnings, rather than their share prices.

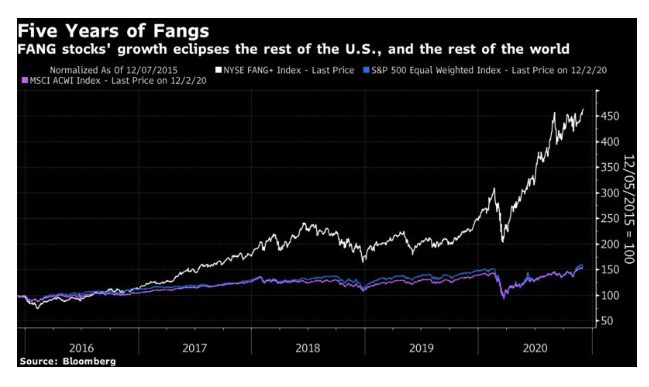

The phenomenon continues. The NYSE Fang+ index hit a new all-time high Thursday. Over the last five years, its performance has dwarfed that of the S&P 500, and the MSCI all-world index. While smaller stocks are beginning to make a relative comeback, the FANGs’ share prices are as high as they have ever been in absolute terms.

So, much of the planet has seen corporate earnings behave much as we would expect in a world of very low interest rates (which is to say, in a very sluggish economy). But a small group of U.S. companies have managed to defy that logic completely. And now earnings estimates are rising as expectations of a post-vaccine boom take hold. That, logically enough, leads stocks to trade at a higher multiple of past earnings. It is earnings expectations, not rates, that have brought the market up in the last month or so, on this logic, and it would be an earnings disappointment (presumably sparked by some disappointment with distribution of the vaccine) that would bring it down again.

As Minack summarizes:

In short, the US has been exceptional—relative to both its own history and other markets—by re-rating in the low-rate post-GFC cycle. The reason global equities are re-rating now is because of improving growth expectations, not because rates are low. If the rally were to correct—and I think it’s getting frothy— then the catalyst will be a growth scare, not a rate scare. Having said that, it’s a terrific combination for equities if growth does improve as expected next year and rates stay low. That combination would be more beneficial for de-rated non-US markets than the re-rated US market.