NIRP Problem #2: Betraying Lord Keynes

In 2008 the whole financial system was on the verge of collapse. Then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke saw little choice but to use every tool in the Fed’s toolbox. So he cut rates, among other things. As Walter Bagehot noted (there’s more on him below), the purpose of a central bank is to provide liquidity at a price in the middle of a crisis. The Fed decided to set the price very low, but they did do the appropriate thing by adding liquidity. However, they overstayed their welcome because of lingering timidity.

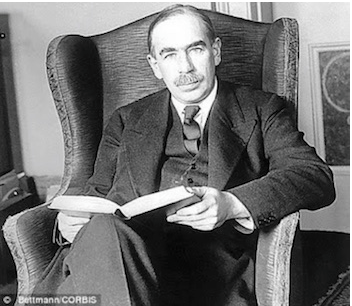

I think they made the right move in 2008, even if I disagreed with the actual way they implemented it, but keeping rates near zero years later is harder to defend. Doing so has punished savers without stimulating growth. Why the Fed’s hundreds of PhDs didn’t know this would happen is beyond me. Even their demigod, John Maynard Keynes himself, said interest rates have to reflect reality.

Even if I disagree with some of Keynes’s conclusions, and especially with the way his disciples have used his work, I have to recognize and acknowledge his brilliance. In his magisterial General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, chapter 21, Keynes describes his “theory of prices.” This includes interest rates, which as we saw above is simply the price of liquidity. You can read the full chapter here. I will quote from its last section (this gets a little academic, but work through it, especially the areas that I put in bold). Remember, this was in the ’30s, in the middle of the Great Depression.

Today and presumably for the future the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is, for a variety of reasons, much lower than it was in the nineteenth century. The acuteness and the peculiarity of our contemporary problem arises, therefore, out of the possibility that the average rate of interest which will allow a reasonable average level of employment is one so unacceptable to wealth-owners that it cannot be readily established merely by manipulating the quantity of money. So long as a tolerable level of employment could be attained on the average of one or two or three decades merely by assuring an adequate supply of money in terms of wage-units, even the nineteenth century could find a way. If this was our only problem now – if a sufficient degree of devaluation is all we need – we, today, would certainly find a way.