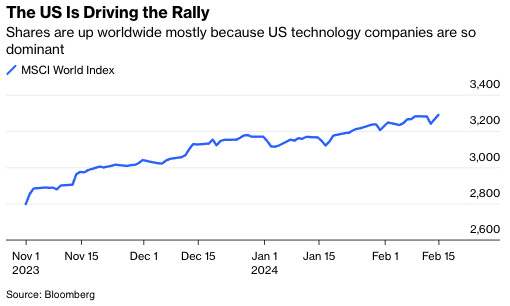

The worldwide dominance of U.S. equities is increasingly obvious. Of the top 10 components of the MSCI global stocks index—which itself now consists of about 70% U.S. stocks—eight are U.S. technology companies. The S&P 500 has breached the 5,000 level. On most days, Apple or Microsoft alone is more valuable than the entire stock markets of major European countries. By one estimate, last year publicly traded U.S. firms accounted for 44.9% of global market capitalization.

All these gaudy numbers raise a question: Is the world on the cusp of a new American century, at least in the corporate realm? The answer is a qualified “yes.”

One reason why U.S. equities are gaining in relative terms is that the Chinese stock market has been crashing. China’s stock market has not traditionally been very representative of the broader Chinese economy, but this decline in equities coincides with broader economic troubles: a burst real estate bubble, local government debt problems, and high youth unemployment. The risk is rising that China’s economic future lies with state-owned enterprises, rather than private capital.

A related issue is that the European Union has not yet rebounded into steady economic growth, whereas the U.S. economy remains strong. It is hard to say how much that reality influences particular share prices, but it does not hurt the relative prospects of U.S. equity markets.

A further reason for the U.S. success: the rise of tech as an economic force. The most profitable tech companies tend to be very large, usually because the software can be readily scaled, or (as in the case of Apple, for example) the supply chain is difficult to replicate. Most very large global tech companies were started in the U.S.—which is their natural Western home, given the tech regulations and market fragmentations of the EU. AI innovations may cause U.S. tech companies to rise all the more.

And over time, pharmaceutical companies might be expected to become more like tech companies, as they explore computational and synthetic biology. Nor is it difficult to imagine some large educational companies arising, as tech innovation could spur growth in this field.

And if investors see tech as continuing to rise in importance, that will favor even more value concentration in U.S. public markets. To understand why, consider electric utilities, which often have national roots. To the extent electric utilities rise in importance, that will strengthen various national equity markets but not the U.S. market overall. At the moment, however, tech seems poised for stronger growth than do the more localized economic sectors—favoring the predominance of U.S. equity markets.

The major U.S. tech companies sell to the entire world. Therefore part of the relative rise of U.S. equities is about the liquidity and prestige of U.S. markets, not just U.S. economic success. U.S. listings will dominate, and all the more over time, even when U.S. customers are not the main source of revenue. Say you found a successful French AI company. Wouldn’t you prefer to be listed on the Nasdaq rather than on Paris Stock Exchange? A Nasdaq listing may make it easier to raise money, and the rest of the world will have a better understanding of the rules under which your securities are governed.

There is thus a self-reinforcing liquidity effect favoring the dominant market for equities. That is one version of a new American century, and it does not require U.S.-based companies to do all the heavy lifting. Nonetheless, the major companies of the world will play by America’s rules, and continue to court its favor.

The biggest challenge to the dominance of the U.S. equity market likely will come from China in growing sectors such as electric vehicles and solar panels. Still, China is more likely to end up as a separate, somewhat segmented set of equity markets, rather than a true global rival to the U.S.

And, just to fill out this rosy picture of America’s economic future, the U.S. is doing well in other kinds of financial markets as well, including venture capital, private equity and private credit. The financialization of an economy does carry risks, but a lot of the recent developments are about deleveraging and greater maturity-matching—which should contribute to stability rather than damage it.

Of course, in many ways America’s global influence is in decline. So maybe it is unseemly, if not inappropriate, for the U.S. to celebrate its increasing global financial dominance too loudly. At the very least, however, a cautious and self-critical American pride is called for. If only we could bottle that and sell shares in it, too.

Tyler Cowen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, a professor of economics at George Mason University and host of the Marginal Revolution blog.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.