As I wrote recently, narratives can explain a lot. The narrative widely cited to justify the optimism at the day’s beginning was “back to work.” This was a national holiday weekend in the U.S. and the U.K., and it came with plenty of people socializing as normal and basking in the sun. There may be ugly arguments in both countries over the rights and wrongs of the lockdown and social distancing, but there is a growing sense that the virus has done its worst, at least for now. Why this narrative led to quite the ecstatic start to the market day is less clear—maybe it was psychologically important to see photos of people in the sun.

The narrative to explain why the market fell again in late afternoon surrounded a news story that the U.S. was considering sanctions against China over the situation in Hong Kong, with the president saying that something could happen by the end of the week. This is plainly market-negative, and a good reason to sell stocks. But as the entire long weekend had offered a series of reasons to treat the “New Cold War between the U.S. and China” narrative with deadly seriousness, and the markets had nevertheless zoomed off into bullish territory to start the day, it isn’t clear why this particular escalation should suddenly have an effect.

The “back to work” and “new cold war” are both reasonably accurate narratives that counteract each other. We still need an explanation for why traders took one of them seriously at the beginning of the day, and then felt persuaded by the other toward the end. That explanation might have something to do with the technicalities of how algorithms operate. Value has been doing terribly compared to growth for a long time. For some reason, plenty of people seemed to decide that Tuesday was the day to snap up bargains. Looking at the course of the day, value stocks surged at the start and never gave up their gains—growth stocks were more insipid and given away ground before news of the potential China sanctions. The “back to work” growth narrative might not have been so strong in the first place:

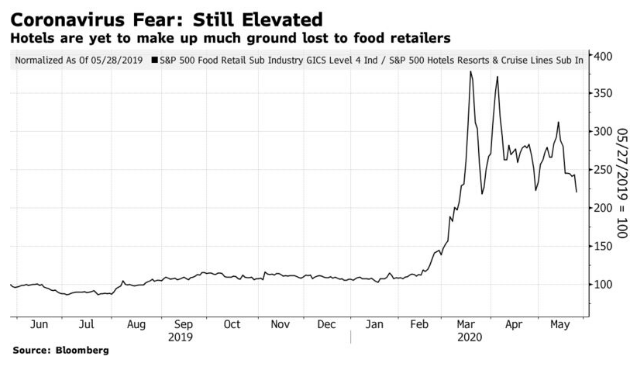

For another shred of evidence, I returned to the “coronavirus fear” measure that I started charting back in March, comparing the performance of two sectors directly affected by the lockdown; food retailers (which benefit) and hotels and cruise lines (which absolutely don’t). This shows that coronavirus fear is near its post-March low, but still hasn't broken out. On this simple measure, there wasn’t a big breakout in optimism about the chances of an early end to the lockdown Tuesday.

For another gauge of the growth narrative, we can follow the suggestion of Chris Watling, founder of Longview Economics in London, and look at whether there is support in other markets for the implicit narrative of a strong recovery in the making. Cutting a long story short, there isn’t. Look at the Baltic Dry index of shipping rates, a volatile but reliable long-term indicator of confidence in global trade. It avoided hitting its historic low from 2016, when the world was gripped by fear of a Chinese devaluation, but it gives no sign of an incipient recovery:

Much the same is true of industrial metals, also up a little from recent lows, but looking historically weak. If we move on to the more cyclical parts of the stock market that aren’t part of the “FANG” complex of dominant internet groups, we again find little confirmation for any great resurgence or cyclical rebound. Watling in particular draws attention to the Stoxx index of global banks, which has only just lifted off its lows for the decade. Bank investors are braced for some horrible second-order effects of the Covid crisis. Meanwhile, bond yields remain obdurately low and give no hint of a major reflation ahead: