According to Wikipedia, “The bogeyman is a common allusion to a mythical creature in many cultures used to control behavior. This monster has no specific appearance, and conceptions about it can vary drastically from household to household within the same community; in many cases he has no set appearance in the mind of an adult or child, but is simply a non-specific embodiment of terror.” Different cultures have different names and physical representations for the bogeyman, and investors are no different. We have terrible monsters that we fear may destroy our portfolios, and we call one of the scariest of them volatility.

While the bogeyman is mythical (I hope!), volatility is real and can cause serious damage. To understand why investors have such a hard time coping with volatility, we first need to define three cognitive biases at work in today’s investment environment:

1) Recency bias – something that has recently come to the forefront of our attention, regardless of how long established it is, suddenly seems to appear with improbable frequency.

2) Negativity bias – we tend to have a greater recall of unpleasant memories than positive memories.

3) Loss aversion – our dissatisfaction with losing money tends to be greater than our satisfaction with making money.

The level of volatility varies dramatically, and so does investor fear and panic selling, waxing when volatility rises, waning when it falls. Recent studies have pointed to demographics as an important driver of panic selling. The theory is that as people get closer to retirement, the prospects of a large (20-30%) loss in financial assets can have a much more pronounced effect on their sense of well-being. Wealth preservation instincts kick in much more quickly than for younger (and typically less wealthy) savers.

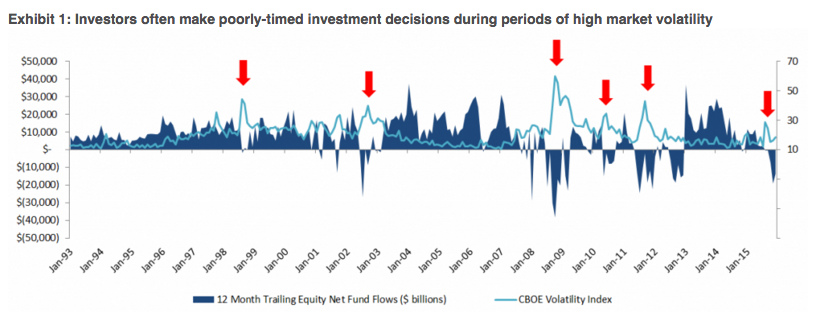

The reality is that there is little opportunity for return without volatility. Therefore, the bogeyman effect of holding long-term savings in cash to avoid volatility (the financial equivalent of hiding under the sheets) is detrimental to achieving long-term goals. This effect tends to be more pronounced during the episodic spikes in volatility. The significant spike in volatility in 2008 and 2009 led to significant withdrawals from long-term investment funds over the same period. Less pronounced effects can also be seen when comparing 2001-2003 and 2011 -2012. Conversely, flows picked up when volatility returned to “normal” levels. Investor behavior of this type is consistent with the three behavioral biases.

Sources: Morningstar Direct, Bloomberg and Columbia Management Investment Advisers, LLC. 12-month trailing equity net fund flows from Morningstar Direct and represents all open-end international equity and U.S. equity funds, excluding fund of funds (monthly data), as of December 31, 2015.

Past performance does not guarantee future results. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.