Now combine a weak recovery with NIRP. If, in the long run, asset prices are a reflection of interest rates and economic growth, and both those are just slightly above or below zero, can we really expect stocks, commodities, and other assets to gain value?

The upshot is that whatever traditional investment strategy you believe in will probably stop working soon. Ask European pension and insurance companies that are forced to try to somehow materialize returns in a non-return world of negative interest rates.

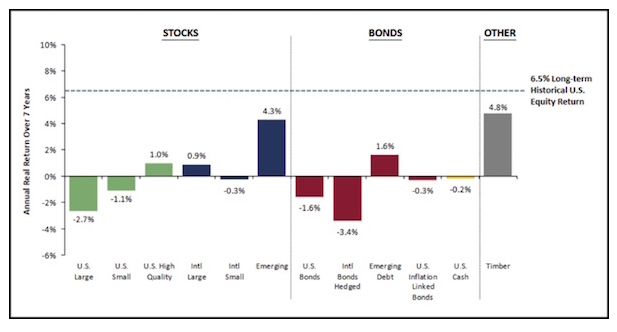

All bets may be off anyway if the latest long-term return forecasts are correct. Here’s GMO’s latest 7-year asset class forecast:

See that dotted line, the one that not a single asset class gets anywhere near? That’s the 6.5% long-term stock return that many supposedly wise investors tell us is reasonable to expect. GMO doesn’t think it’s reasonable at all, at least not for the next seven years.

If GMO is right – and they usually are – and you’re a devotee of any kind of passive or semi-passive asset allocation strategy, you can expect somewhere around 0% returns over the next seven years – if you’re lucky.

Note also that nearly invisible -0.2% yellow bar for “U.S. Cash.” Negative multi-year real (adjusted for inflation) returns from cash? You bet. Welcome to NIRP, American-style. Would you like that with fries?

The Fed’s fantasies notwithstanding, NIRP is not conducive to “normal” returns in any asset class. GMO says the best bets are emerging-market stocks and timber. Those also happen to be thin markets that everyone can’t hold at once. So, prepare to be stuck.

Next week we will look at what current and future monetary policies mean to pension funds and taxpayers, not to mention retirees and those who would like to retire sometime in the next 10 years.

Maine, New York, Montana, Iceland (?), and Denver

I am finishing up this letter from Las Vegas, dashing off the final part before I go deliver a speech. We fly back tomorrow, and then I’ll be home for about 17 days before heading off to Maine for the annual Camp Kotok gathering of economists, analysts, media, and assorted other ne’er-do-wells to fish and share a few adult beverages. In most groups where you gather 50 fishermen, the biggest whoppers are about the fish that got away. In the case of this assembly in Maine, the biggest tall tales are about our views on the economy. Let’s just say that not everyone agrees; and over the 10 years that my son Trey and I have been attending, I have found that trying to persuade the rest of this bunch about the proper way to view the economy and markets is a thankless, hopeless task. Nevertheless, it is a duty that I willingly take up, year after year, along with my fly rod.

After Camp Kotok I fly to New York for a few days before traveling cross country to Flathead Lake, Montana, to spend time with my business partner and good friend Darrell Cain and a bunch of young rocket scientists. With their help I’ll research a chapter on the future of space for my upcoming book and try to write a few other chapters as well. Note to my publishers: I actually did finish the last chapter and final edits of Code Red at this very retreat, so it is possible to get some work done there.

Then I have been offered an opportunity to go to Iceland and research the future of energy and a few other topics for a few days in the middle of August. We’ll see if that materializes.

I will be in Denver on September 14 for the S&P Dow Jones Indices Denver Forum. If you are an advisor/broker and are looking for ideas on portfolio construction, I will be there along with some other friends to offer a few suggestions. Sometime in the fourth quarter, I will actually go public with what I think is an innovative way to approach portfolio construction and asset class diversification. This approach makes more sense for what I see coming in the macroeconomic future than the general 60/40 traditional investment model that most people and funds tend to follow. I’ve been thinking about this portfolio model for a very long time, and we are putting the final touches on the project. While the investment model itself is relatively straightforward, all of the details involved with making sure that all of the regulatory i’s and business t’s are crossed – the stuff that has to happen behind the scenes – is far more complex.

The last few days have been like “old home week.” I had many more friends than I knew coming to Las Vegas for FreedomFest. Way too long a list to mention everyone, but I did get to sit down with Steve Forbes and Bill Bonner for a long coffee, talking about the “old days” of investment newsletter and magazine publishing – how things have changed over the last 35 years, and yet the principles of the business are generally the same. We just have to use ever-changing new methods to meet our objectives. I moderated a panel with Steve Forbes and Rob Arnott, which, if schedules permit, I will try to reproduce at my conference next year. And then I got to listen to George Gilder and spend a long lunch comparing notes on the roles of gold and Bitcoin and the actual mathematical basis for a new approach to economics. Heady stuff…

It is quite likely that a large fraction of my list does not know who Bill Bonner is. He may be the largest private publisher in the world. I asked him how many newsletters and magazines he now publishes, and he shrugged his shoulders and said, “More than a few hundred.” He started Agora back in the late ’70s and just kept growing, empowering other people to create and publish their own letters with his backing. In contrast to the normal top-down model of publishing, Bill is a venture capitalist of publications. He provides the backbone, but you have to eat your own cooking and create your own cash flow. He is now in over 13 countries and languages and probably delivers newsletters in every country in the world.

It is a long way from 1982, when I was also in the newsletter publishing business and Bill and I were doing enough together over the phone that I decided that this Texas country boy needed to travel to Baltimore to meet him. I flew into Baltimore, rented a car, and drove to his office. Younger readers have probably watched a show on HBO called The Wire. Believe me, what they depict on that show is an upgrade from where Bill’s offices were. He literally bought his office building for a dollar from the city (and now contends that he overpaid) in what was a very scary part of town. I remember parking a block away and actually being afraid to get out of the car to walk to his office. Remember, I was 32 years old and hadn’t been out of Texas very often. I was not your worldly wise, globetrotting, sophisticated, unafraid-to-walk-through-the-middle-of-riots-in-Africa raconteur that I am today. (Please note sarcasm, although I have walked into riots in Af rica. A story for another day.)

I finally worked up the courage to walk over to Bill’s office, knocked on the door, and heard about half a dozen bolts and latches being worked on the other side. Finally the door eased open a few inches, and an anxious young woman peered out at me. Probably noticing that I was more nervous than she was, she opened the door to let me in, then hurriedly closed the door and refixed all half-dozen latches. I walked up a few levels (this was a four-story row building) to an open-floor office where there were a dozen desks and people busily working amidst a mountain of files and papers strewn everywhere in what was clearly a filing system that only a group of ADD writers could appreciate.

Bill and I seemed to recognize the country boy in each other and hit it off, and we’ve been fast friends ever since. Thirty-four years later, Bill hasn’t changed all that much from the wrong-side-of-the-tobacco-farm guy from rural Maryland that he was back then – except for the missing hair. I travel from time to time to one of the homes he has scattered around the world. He has châteaus in France and haciendas in Argentina, beach homes in Nicaragua, etc. – it sounds more exotic than it really is. He grew up as an all-purpose fix-it guy, not unlike your humble analyst. He differs from me, however, in that he actually still likes to do all that hands-on stuff; so when he buys a château, what it really is, is a monstrous money pit where he tries to do as much of the fix-it work as he can with his own two hands. Ten or fifteen years later, he really has a nice place. And it was good training for his six kids, as he made them work durin g the summers, stripping paint, pulling wires, building stone walls, planting trees, and doing all the little things you have to do when you have a pile of rocks that once upon a time was a magnificent dwelling. Not exactly the life I would want to live if I were a gazillionaire, but good work if you can get it.

Bill may be the best storyteller that I know. That is different from being a good writer. Writers convey information. Storytellers may also convey information, but the package they put around the information is engaging and makes you think. A well-told story around the information allows you to internalize it more easily. We are genetically hardwired to appreciate a good story. We evolved from human beings who spent a lot of time around the campfire, swapping stories. Learning to live in groups and work together is a big part of why our species flourished, and it seems that people who enjoyed a good story survived and passed that predilection on to their descendants, over many thousands of generations.

When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a writer. But to tell the truth, I really want to be thought of as a storyteller. I guess I’ve always wanted to be Bill Bonner when I finally grow up – just without having to build stone walls with my bare hands.

You have a great week. Find a friend or two or three, take them to a long dinner, and spend the time telling stories. Everybody has a few stories. You will find they will help you survive as well.

Your storytelling wannabe analyst,

John Mauldin

John Mauldin is editor of Mauldin Economics' Outside The Box.

This article was originally published at Mauldin Economics.