Key Takeaways

• While the Fed raised its policy rate last week, the more important meeting outcome was the Fed’s guidance on future policy.

• Overall, the Fed’s dots and Powell’s comments point toward a gradual but slowing pace of rate hikes as monetary policy moves closer to a neutral stance.

• However, the disconnect between the market’s and the Fed’s projections for interest rates is growing.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) wrapped up its most recent monetary policy meeting on Wednesday, September 26. While the Fed raised its policy rate, as expected, the more important outcome was the Fed’s guidance on future policy through its statement, a new set of forecasts, and Fed Chair Jay Powell’s press conference after the meeting’s conclusion. The Fed walked a fine line between minimizing the possibility of a harmful pickup in inflation while emphasizing the strength of economic growth and the labor market. However, the market’s response shows the disconnect between the Fed’s and the market’s expectation for future policy is growing.

The Dots

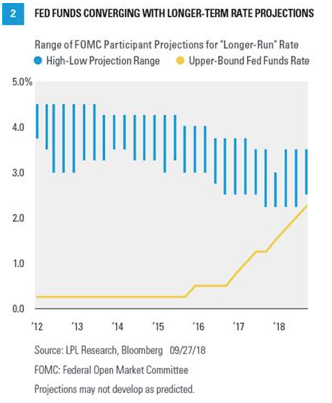

At every second meeting, along with its policy decision and statement, the Fed provides economic and policy projections based on the individual projections of the 12 regional Fed presidents and the 7 members of the Fed’s Board of Governors (with some seats often unfilled due to transitions). Fed members update their interest rate projections in the Fed’s well-known “dot plot,” with each estimate represented by an unlabeled dot. The Fed’s new dots show policymakers project one more rate hike this year (to a fed funds target range of 2.25–2.5 percent), along with three rate hikes next year (to a range of 3–3.25 percent) [Figure 1].

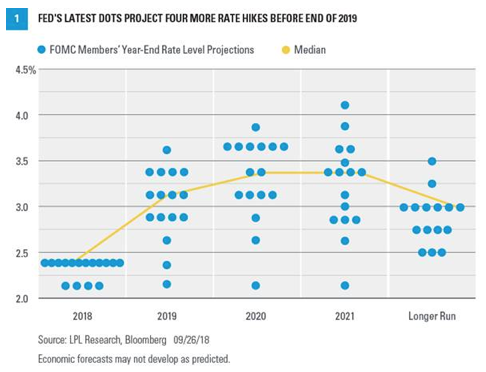

While Powell stated several times in Wednesday’s press conference that the Fed will move forward with gradual rate hikes, the median dot of each forecast implies that policymakers expect the pace of hikes to start slowing next year. The dots show that members expect the fed funds rate range to peak at 3.25–3.5 percent at the end of 2020 before declining to a “longer-term” rate of 3 percent. This longer-term projection is the best gauge of the “neutral rate”—or the point where monetary policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive. The neutral rate is a practical idea rather than a known macroeconomic variable, and it takes a pragmatic policy approach to move toward the neutral rate while avoiding the risks of overtightening or leaving policy too loose. Although the median estimate for the longer-term rate is 3 percent, the dots project a longer-term rate anywhere from 2.5–3.5 percent [Figure 2]. The takeaway here is that although the longer-term projection is a helpful indicator, there is still a degree of uncertainty in determining the neutral rate; and ultimately, the incoming economic data will continue to determine the policy path that provides that best balance of the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment.