Globalization then faced a stronger pushback from both the left and right sides of the political aisle within the United States as some global trading partners could be perceived as a competitive threat. This perhaps culminated in President Trump’s "America first" policy—which notably took aim at the emergence of China. Across the Atlantic, the UK’s "Brexit" vote affirmed similar sentiment.

We’re Shifting Toward Widespread ‘Regionalization’, Not ‘Isolationism’

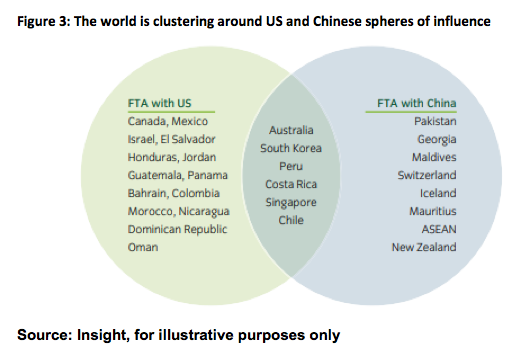

The end of hyper-globalization does not imply a retreat into global isolationism. Instead we believe a more likely scenario is that the world will cluster more strongly into regions around so-called ‘spheres of influence’ based upon economic and geopolitical ties.

The European Union is perhaps the largest example of a multilateral regional bloc, with Germany and France at its forefront. Future regional clustering is likely to occur around the United States and its emerging geopolitical and economic rival, China. Many countries are aligning with one, or the other, while others attempt to play a careful balancing act (Figure 3).

For example, the United States has (through the USMCA trade pact) strengthened its economic ties to Mexico and Canada. The USMCA includes requirements for localized production and also grants the United States with the ability to veto any free trade agreements between either Mexico or Canada with China.

China, meanwhile, has been busy with its "Belt and Road" initiative, a large-scale infrastructure plan designed to open up and establish improved trade routes across Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America. There is, however, one initiative, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, that is a counter-attempt by certain (largely Asian) nations to form a cohesive economic bloc outside of China’s influence.

Multi-national corporations are underway in shifting towards more localized production and some are shifting production out of China to its neighboring nations. This will likely unfold in a staggered process with some industries taking longer than others to effect the transition. China’s current status as "workshop of the world" is a result of decades of investment and government support aimed towards building huge industrial parks, training workforces and strengthening connections between massive ports and modern logistical networks that would likely take many years to replicate elsewhere.

Corporations operating in the United States may find that re-localizing production may not be straightforward. Government assistance may be needed to subsidize the increased cost of domestic production. This could come in multiple forms, some being direct tax credits or tax incentives, and preferential treatment for domestic producers to help gain a competitive advantage.

Consider The Winners And Losers

Globally, we believe South Korea, Poland,and Malaysia are likely the winners should the effort to diversify away from China persist. Mexico and India would also stand to gain from this shift on a longer-term basis.

In the United States and other more advanced economies, the winners should be the sectors that directly compete with Chinese exports; the sectors that have inelastic enough demand to pass thru higher labor costs to its consumers. However, the areas or sectors of the economy where the demand for goods are more elastic to price changes are less likely to have the ability to pass the increased cost on to consumers and thus will face margin compression.