The spread and acceptance of globalization has been an unrelenting force, but its march forward has lost some steam in recent years—is this the beginning of a new trend towards an outright contraction in globalization or merely a temporary deceleration?

We believe the broader trends of globalization remain in place and will continue to move forward as the benefits are widespread and far-reaching. Credit investors have long benefited from globalization, and now may want to prepare for an element of "regionalization," particularly given some of the supply chain disruptions we have seen as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Rise Of Hyper-Globalization

Globalization gained acceptance and became more prominent following the 1970s. The economic landscape quickly shifted towards free and liberalized international markets for goods, labor and financial capital.

A more global economy became a logical way for businesses to grow and establish additional economies of scale while tapping into new labor markets and eventually a new customer base.

Countries were swift in adopting new trading partners while lowering trade barriers and liberalizing their domestic markets. Supply chains became increasingly complex as first-world multinationals began to shift their manufacturing bases overseas. Several Asian countries became leaders among their peers and exported their way to "tiger economy" status while global financial hubs developed across the United States, Europe and Asia.

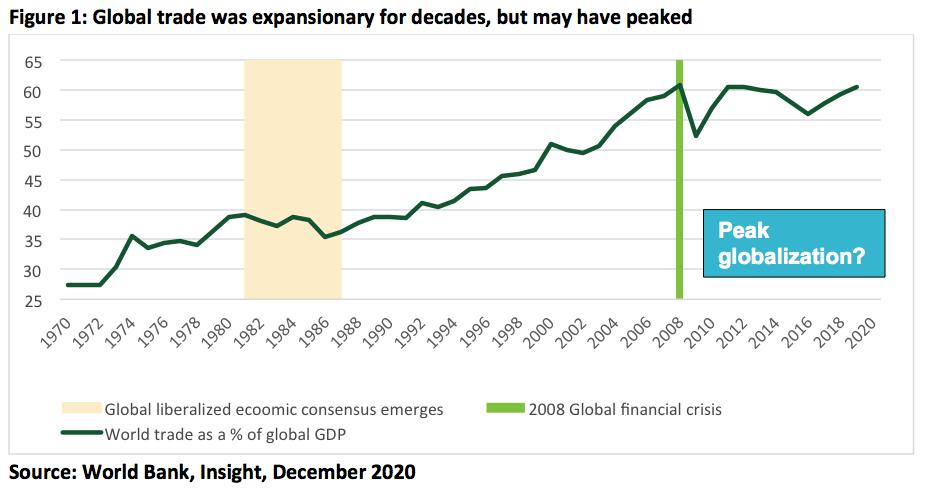

Global trade volumes steadily marched upwards before hitting a peak and flatlining after the 2008 crisis (Figure 1).

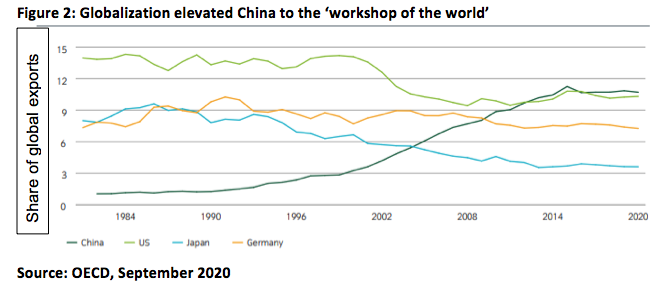

One nation’s meteoric rise in power was fueled by global trade: China. The world’s most populous nation opened its labor market to Western multinationals in the 1980s and eventually joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. China became the fastest-growing economy of the early millennium and its share of global exports overtook many advanced economies (Figure 2).

The United States and many other developed nations benefited from globalization on numerous fronts, but none was more obvious than the ability to leverage lower labor costs. Large, investment grade multinationals quickly saw their labor costs fall while their profit margins increase thus boosting equity valuations and enterprise value. Falling labor costs also heavily contributed to secular disinflation across the West, which persists to this day and is a positive for consumers’ disposable income.

The Fall Of Hyper-Globalization

The financial crisis of 2008 (a globally systemic crisis) exacerbated by the intricate links between not only financial sectors but also countries, took some of the wind out of globalization’s sails. Perhaps globalization took a backseat as the world experienced a contraction in growth, consumers deleveraging and an environment where fiscal austerity became a focus—shining a light on the widening inequality within the advanced economies.