In the United States, the long-term real safe interest rate—the inflation-adjusted return on low-risk investments such as Treasuries—is, in addition to “financial conditions,” the key mechanism influencing both the incentive to build and the balance of net exports (owing to its effect on the exchange rate).

From early March to mid-May 2022, this metric jumped by more than one percentage point as the bond market realized that the U.S. Federal Reserve would soon curtail its efforts to promote a speedy recovery in employment following the pandemic. Then, from late August to early October 2022, it jumped again, this time by an annualized 1.5 percentage points, as bond traders speculated that the Fed might have to tighten monetary policy to avert persistent inflation in an economy that had returned to full employment.

It was these two spikes that created the current interest-rate configuration. Rates today are far higher—around two percentage points—than the level anyone five years ago (before the pandemic) would have estimated the “neutral” rate to be.

The neutral rate, John Maynard Keynes explains in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, is the level necessary to “bring about an adjustment between the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest.” An interest rate that everyone considers to be above the neutral level therefore reflects markets’ confidence that a recession—or at least a substantial slowdown—is only a matter of time. When that time comes, all will depend on whether the Fed recognizes the approaching weakness in time to cut rates and achieve a “soft landing.” This interest-rate configuration has now held for seven months.

The situation has not been fully static, of course. There was another one-point surge between June and October 2023. But that wave soon receded as speculation shifted to questions of when and how fast the Fed would start cutting rates. The 30-year Treasury rate thus is back to where it was in October 2022.

The landing has indeed been smooth. But the pilot has not dared to shift from reverse into neutral. Apparently, the Fed is concerned that nonfarm payrolls keep rising. On a seasonally adjusted basis, there were 275,000 more jobs in February than in January, which is only slightly higher than the average of 250,000 over the past six months. I suspect that the Fed is profoundly uncomfortable with interest rates substantially above what it confidently believes the neutral rate to be, especially now that inflation is very close to its 2% target. But it will not dare to shift out of reverse until it sees signs of slower job growth.

Three explanations could clarify the current situation. The conclusion that interest rates are in excess of the neutral rate could be based on an erroneous analysis. Or there could be an error in how we measure the state of the economy. Or, third, the Fed may have committed the Wile E. Coyote error.

Taking these explanations in reverse order, if economic weakness is indeed coming, the Fed will soon wish that it had started cutting rates in January 2024. Remember, private-sector decisions to cut back on building, and to re-source purchases to overseas suppliers, were paused in 2022 and delayed until 2023 as people waited to see how much the Fed would tighten. If firms then followed through on those postponed decisions between May and October 2023—as the 10-year Treasury yield ran up temporarily from 3.53% to 4.93%—the impact on employment patterns should start to hit the economy right about now.

In pursuit of the roadrunner, Wile E. Coyote (a classic Looney Tunes character) always runs off the edge of the cliff but does not begin to fall until he looks down and realizes he’s running in air. I was fairly confident that this was where the Fed stood six months ago. But as time passes without anything happening, I become more torn.

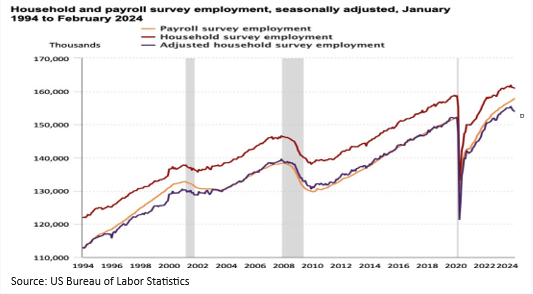

What if the measurements are wrong? The consensus has long been that the U.S. payroll survey is superior to the household survey. But in the past couple of years, a gap has emerged between these two surveys. While the payroll survey records 2.7 million more jobs than a year ago, the household survey records only 700,000 more people working in those jobs than a year ago.

If the labor market is as weak as the household survey suggests, that weakness should have already shown up in consumer spending. It has not.

That leaves the possibility of a faulty analysis. The near consensus since the start of the pandemic has been that there are powerful fundamental factors keeping the neutral interest rate very low, and that there have been no major changes to those fundamentals. The neutral rate therefore should still be very low, implying that the high policy rate is inappropriate to an economy at full employment with inflation near its target.

But if there is one lesson that I have learned in more than 40 years of trying to understand the business cycle, it is that there is no empirical regularity in the macroeconomy that can be trusted not to crumble beneath our feet in a remarkably short time.

J. Bradford DeLong, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research and the author of Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century (Basic Books, 2022). He was Deputy Assistant U.S. Treasury Secretary during the Clinton Administration, where he was heavily involved in budget and trade negotiations. His role in designing the bailout of Mexico during the 1994 peso crisis placed him at the forefront of Latin America’s transformation into a region of open economies, and cemented his stature as a leading voice in economic-policy debates.