Recent advances in artificial-intelligence technology have raised the specter of mass displacement in labor markets. It is no longer just blue-collar factory and construction jobs that are at risk of being taken over by machines; a wide range of professional and service jobs have become newly vulnerable as well.

In the United States, up to 47% of all jobs could be automated in the coming years. So, is the world headed toward economic devastation, or will this era of job destruction also bring comparable levels of job creation?

An innovation’s impact on employment depends on the ratio between its displacement and compensation effects. The type of innovation is important. Whether generative AI – including large language models like ChatGPT-4 – will be good for workers depends significantly on whether it leads to more innovation in products or processes.

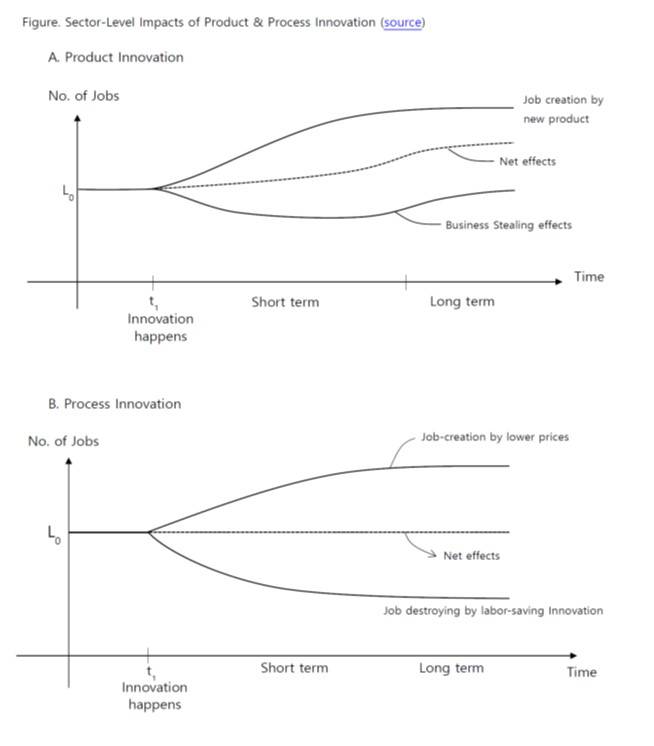

Product innovation – the introduction of a new or updated good – tends to have a significant compensation effect, as demand for the new product and the associated jobs grows. To be sure, product innovation can reduce employment via the so-called business-stealing effect (BSE), in which one firm’s innovation in a sector leads to job losses among its competitors. But this effect is unlikely to persist, as laggards would, sooner or later, embrace or imitate their competitors’ product innovations.

This diffusion of product innovations could restore – or even boost – overall employment in the sector. Once a large enough share of firms has adopted innovations, the upward trend in employment would flatten, but often at a higher level than where it began. The long-term net effect of product innovation on employment is likely to be positive.

In fact, in a recent study, Jisun Lim and I found that a one-percentage-point increase in the share of employment by product-innovating firms in a sector tends to lead to a 0.1-percentage-point increase in that sector’s (net) job-growth rate in the long run – almost double its short-run effect. The greater long-run increase probably reflects the fact that the job-displacing BSE wanes over time.

With process innovation – the introduction of a new method of production – the outcome is more uncertain. Because new processes typically boost labor productivity, fewer workers are needed to produce the same output, implying a significant displacement effect. Unlike the BSE in product innovation, these job-destroying effects do not dissipate over time.

But if process innovation reduces production costs and, in turn, the price of the goods produced, it could lead to increased demand, higher sales and profits, and more investment by the business – including in hiring more workers. This balance between these positive and negative trends changes little, regardless of how many firms in a sector embrace the innovation.

It is thus virtually impossible to predict whether the net effects of process innovation on sector-level employment will be positive or negative in the long run. But the most likely outcome is relatively neutral. Process innovation seems to have no significant net employment short- or long-run effect in a sector.

Of course, generative AI applications like ChatGPT will not lead to only one type of innovation. Rather, they will enable advances in both products and processes. If process innovation has little net effect on employment, and product innovation has a positive net effect, then generative AI’s overall effect could be positive.

Fortunately, there is reason to believe that generative AI will bring considerable product – not only process – innovation. A PwC study estimates that 45% of total economic gains generated by AI by 2030 – almost $16 trillion, representing a 14% increase in global GDP – will come from product enhancements, stimulating consumer demand. AI, the report observes, “will drive greater product variety, with increased personalization, attractiveness, and affordability over time.” This bodes well for employment.

If this sounds overly optimistic, recall how gloomy employment forecasts for the US were a decade ago, yet the US today enjoys record-low unemployment. It is worth noting, however, that even if innovation-driven job creation outpaces job losses, a skills mismatch will arise. Government-sponsored re-skilling and up-skilling initiatives will be vital to ensure that workers can fill the newly created jobs.

Nonetheless, fears of mass unemployment seem to be overblown, and should not be allowed to stand in the way of innovation. Though humans’ average working hours are likely to decline over time – in line with a longstanding historical trend – there is no evidence that generative AI will lead to lower employment in the long run.

AI applications like ChatGPT may well turn out to be precisely the kind of general-purpose technology that has powered entire eras of technical progress and growth. As the twentieth-century economist Joseph Schumpeter would put it, AI may be a “key factor input,” much like electricity or microelectronics. It should be embraced, with governments launching diverse policy initiatives to stimulate innovation.

This is what South Korean firms realized in their competition with Chinese firms. Whereas the Korean government used to be hesitant about automation, owing to potential job-replacement effects, now it vigorously supports its manufacturing firms’ introduction of “smart factories.” Owing to this transformation, firms have reduced costs and increased productivity, thus regaining their competitiveness. As sales rebounded, they hired more workers.

The lesson is clear: countries and companies that fail to embrace AI are at risk of being left behind and losing jobs to more innovative foreign companies. That is the real threat workers face.

Keun Lee, a former vice chair of the National Economic Advisory Council for the president of South Korea and a former president of the International Schumpeter Society, is distinguished professor of economics at Seoul National University, winner of the 2014 Schumpeter Prize, and the author of "China’s Technological Leapfrogging and Economic Catch-up: A Schumpeterian Perspective" (Oxford University Press, 2022).