Investors have poured an astonishing $1 trillion of cash into equities funds in the past 12 months, or more than the combined inflows of the past 19 years. At the peak in January, retail investors accounted for almost one quarter of U.S. equities trading, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

An estimated 16% of U.S. adults have invested in crypto, according to Pew Research Center; among twenty-something men, that proportion is closer to half. In 1929 shoeshine boys gave out stock tips; today’s teenagers ask their parents to open a crypto trading account on their behalf.

The short explanation for all this feverish activity is that thanks to central bank and government stimulus, far too much money is sloshing around in the financial system. The aggregate money supply has increased by $21 trillion since the start of 2020 in the U.S., China, euro zone, Japan and eight other developed economies. “Stocks only go up” isn’t just a wry catchphrase: Essentially it’s been the lived experience of young investors this past decade. And so they ignore nosebleed valuations and buy the dip.

But something’s changed too in the culture of investing. It’s no longer enough to admire a company or asset and buy the stock or token. Some of the biggest investing trends have become an extension of personal identity, akin to your religion or your sports team. Sometimes that connection is overt: From Christmas Day the home of the L.A. Lakers will be renamed the Crypto.com Arena. Footballer Tom Brady has launched his own NFT collection.

These movements can be fun and empowering, but financial super-fandom can quickly become toxic. I worry that the same forces diminishing modern politics — partisan divisions, pervasive distrust, social media echo chambers, misinformation, cancel culture and conspiracy theories — are seeping into the investing world, where they’re warping capital allocation, inflating a series of bubbles and challenging the ability of regulators to protect investors and the markets.

In some respects, this time really is different. Easy to use, commission-free brokerage apps like Robinhood have given millions of neophytes the tools to play at being a Wall Street trader.

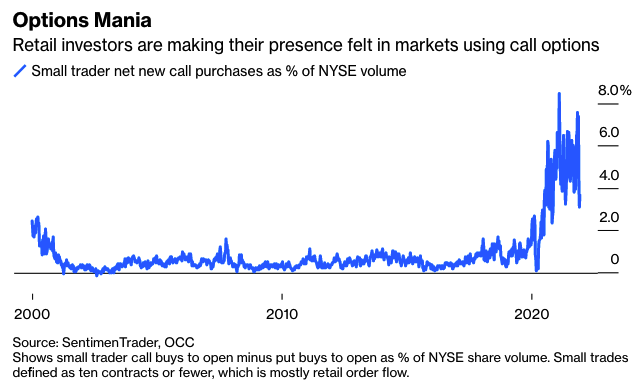

Instead of sticking their money in a boring index fund, young investors are making concentrated bets on single stocks and using cheap short-dated out-of-the money call options (speculating the price of the stock will quickly increase before the option expires). It’s the financial equivalent of buying lottery tickets.

It can be an effective way to squeeze the underlying shares higher (because option sellers hedge their position by buying the stock). It often attracts momentum-buying from hedge funds and other institutional investors, which magnify the price moves. And options are also a huge money-spinner for digital brokerages. Problem is, inexperienced retail investors may not fully understand the risks, until it’s too late.

“It’s much more like gambling,” says Bloomberg Intelligence market structure analyst Larry Tabb. “The options premiums might seem pretty small but you can easily end up losing your entire investment.”

Speculative assets have evolved, too. In 2000 investors could easily comprehend the business model of a Pets.com, say. There’s now a much higher degree of financial abstraction: Think SPACs, NFTs, Web3, DeFi ( “decentralized finance”) and the metaverse. This abstraction excites intellectual curiosity but the harder something is to explain, the easier it is for promoters to hype it to people lacking a financial or technical background.

Fearing they’ll be accused of stifling innovation or capital formation, regulators have mostly allowed the party to continue. Digital assets typically aren’t registered and regulated as financial securities. Crypto trading often happens on opaque, offshore exchanges. SPACs can publish fantastically optimistic financial projections, which traditional IPOs avoid due to liability risks. It smacks of regulatory arbitrage on a grand scale.