Last year, the Trump administration abandoned a regulation designed to protect U.S. savers from conflicted investment advice. Known as the fiduciary rule, it would have required more brokers and insurance agents to disclose when they’re getting paid to steer people into certain investments. It also would have banned the sale of certain retirement products when they aren’t in savers’ “best interest.”

So did the rule’s demise benefit Americans by empowering them to “make their own financial decisions,” as Trump indicated he wanted to do? The evidence suggests not. Sales of potentially questionable investment products have soared, and retirees stand to end up billions of dollars poorer.

One prime example: fixed-indexed annuities. Often aggressively marketed and loaded with fine print, they promise participation in the stock market’s upside with no risk of loss. Although some can be useful for tax and insurance planning, when mis-sold they can amount to an unduly complex version of a strategy that investors can replicate at much lower cost. Among their attractions for insurance agents: high commissions and bonuses that have included beach vacations and cruises.

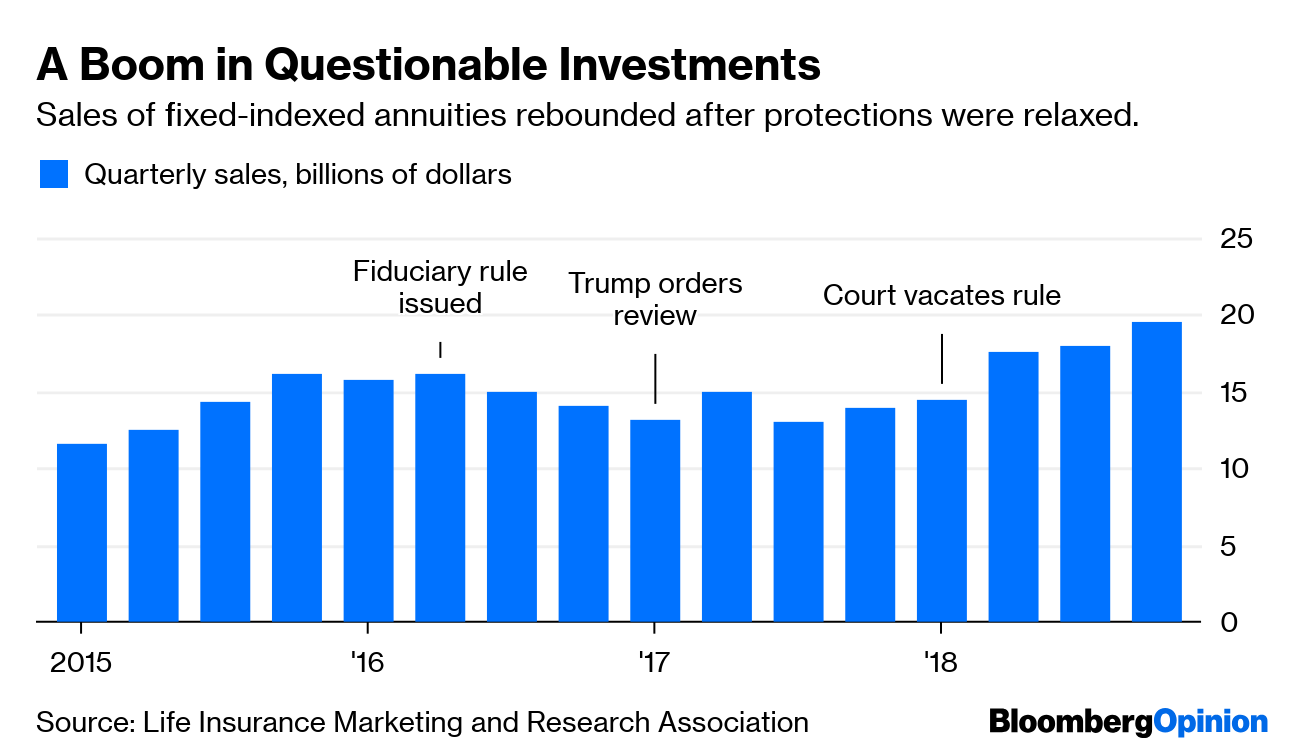

Insurance agents’ behavior suggests some of them doubt that these products always serve clients’ best interest. Sales of fixed-indexed annuities plunged after the Labor Department issued its final version of the fiduciary rule in April 2016. Predictably, sales recovered quickly after June 2018, when the Trump administration allowed a court to vacate the rule with no pushback from the Labor or Justice departments. In the last three months of 2018, sales amounted to $19.5 billion, according to the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association. That’s up 40 percent from a year earlier.

In New York state, which has unilaterally adopted aspects of the fiduciary rule, far fewer insurers sell such products.

How much do savers stand to lose? Consider one product that a major insurance company marketed to me: a 10-year annuity linked to the S&P 500 Index. Based on this annuity’s formula and the price at which it was offered, a client would have foregone on average an estimated $54,000 in profit per $100,000 invested over any 10-year period going back to 1989. That’s compared with a simple combination of U.S. Treasury bills and S&P 500 index funds that offers the same downside protection as the annuity with less credit risk and more liquidity.

The marketing materials an agent sent me seemed to play on fear, showing a potentially faulty comparison of the annuity’s returns to the loss a pure stock position would have suffered during the 2008-09 crash. And the materials did not highlight crucial information such as hefty withdrawal fees and the insurance company’s right to reduce payouts.

Such products are just the tip of the iceberg. Every year insurers come out with an array of new annuities employing “black box” strategies that are all but impossible for outsiders to understand. One could be forgiven for suspecting that some such strategies have been tweaked to make it difficult for a lay person to accurately assess their return potential.