Key Points

• The Federal Reserve is likely to raise rates again this year, but that doesn’t mean fixed income investors need to wait on the sidelines for a better entry point.

• Short-term bonds and bond funds can offer slightly higher yields than Treasury bills and money market funds, with less price volatility than longer-maturity bonds.

• Investments with floating coupon rates can benefit from higher rates, but not all floaters are alike.

• Intermediate- and long-term bond yields may still make sense, as a Fed rate hike doesn’t necessarily mean that all bond yields will rise.

The Federal Reserve is poised to raise rates again later this year. While the prospect of rising bond yields often spooks bond investors, we think there are investments that make sense now, in anticipation of rising rates, and may even benefit once the Fed hikes rates further:

• Short-term bonds allow investors to take advantage of higher rates relatively quickly, but do come with more interest rate risk than shorter-maturity Treasury bills or money market funds.

• Investment-grade floating-rate notes can adapt to rising short-term interest rates more quickly than short-term bonds, but they carry additional credit risk.

• Bank loans are aggressive investments that offer floating coupon rates, but their coupons might not all reset higher after a rate hike due to the prevalence of coupon “floors.”

• Intermediate-term bonds, which should make up the core of most fixed income portfolios, in our view, aren’t as sensitive to Fed policies. Intermediate- and long-term bond yields are influenced more by growth and inflation expectations, which remain low.

Short-term bonds

Short-term bonds and bond funds—generally including bonds with maturities between one and five years—tend to offer higher yields than investments with even shorter maturities, like Treasury bills and money market funds. With relatively short maturities, short-term bond prices tend to be less sensitive to interest rate changes than investments with longer maturities and higher duration.1

But keep in mind that short-term bond yields are highly influenced by the federal funds rate, an overnight lending rate that the Fed uses to implement monetary policy. When the Fed hikes rates, it’s possible that short-term rates will rise more than long-term rates, which is what we witnessed at the end of last year.

On October 14, 2015, for example, the two-year Treasury note offered a yield of 0.55%. As market expectations for a rate hike later in the year increased, so too did the two-year Treasury yield (remember that bond yields move inversely to bond prices, which were falling during this time). By December 29, 2015, a little after the Fed boosted rates for the first time in nearly 10 years, the two-year Treasury yield had doubled, rising to 1.1%. In fact, two- and three-year Treasury yields saw the sharpest rise of any Treasury bond maturity over that time period, resulting in a -0.68% total return for the Barclays U.S. Treasury 1-3 Year Bond Index.2 While that negative return would only be realized if the investment were sold, it illustrated that, over short time frames, negative total returns are still possible with short-term bonds and bond funds. Over longer investing horizons negative returns have been uncommon, however; that index has generated negative total returns in only two 12-month periods dating back to 1992.3

A benefit of short-term bonds and bond funds, however, is that their short maturity dates allow investors and fund managers to take advantage of any potential rise in yields relatively quickly. As short-term bonds mature, the proceeds can be reinvested in newer bonds offering higher interest rates. For bonds with longer maturities, whether held individually or in a fund, the more time until maturity means it takes longer to reinvest those proceeds.

Investment-grade floating-rate notes

A floating-rate note, or “floater,” is a bond without a fixed coupon rate. Rather, the coupons are usually based on a benchmark interest rate, like the three-month London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), plus a spread. For example, the coupon may be quoted as three-month LIBOR plus 100 basis points, or 1%. If LIBOR were 0.7%, the coupon rate would be 1.7%. Unlike bank loans, which we discuss below, the coupons on most investment-grade floaters do not include a reference rate floor.

The spread can vary based on factors like time to maturity or credit rating. All else being equal, bonds with longer maturities tend to have higher spreads than those with shorter maturities. And bonds with lower credit ratings tend to have higher spreads than those with higher credit ratings. The spread is an indication of risk: investors earn a higher rate than the reference rate to compensate for the risk of holding a corporate bond, such as default risk.

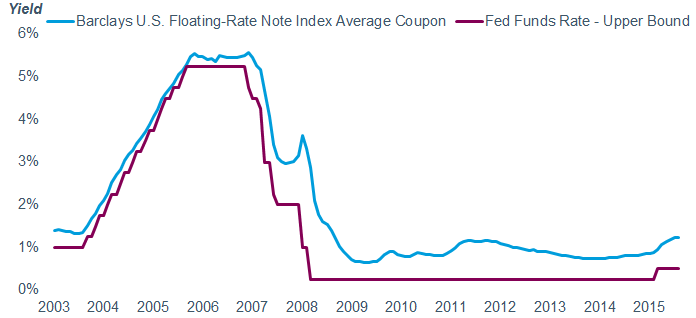

Importantly, those who invest in investment-grade floaters tend to reap the benefits of higher short-term rates quickly, and even in anticipation of a rate hike. Most floaters make coupon payments quarterly, rather than semiannually. By making payments quarterly, floaters can more quickly react to higher short-term rates, rather than potentially waiting for half a year. Also, short-term benchmark interest rates tend to move higher in anticipation of a Fed rate hike. By the time the Fed finally raised rates last December, three-month LIBOR had already risen by a quarter percentage point from the prior month.

Floating coupons benefit quickly after Fed rate hikes

Source: Bloomberg and Barclays. Monthly data as of 5/31/ 2016. Barclays U.S. Floating-Rate Note Index and U.S. Federal Funds Target Rate Upper Bound (FDTR). Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

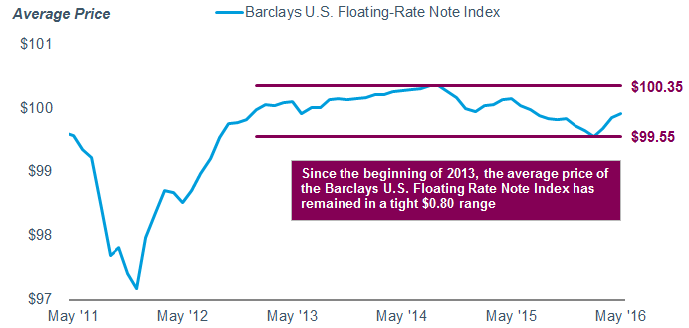

Floater prices tend to be relatively stable, as well, as their floating coupons help limit their interest rate sensitivity. But because they do carry credit risk, there can be periods of price volatility if economic conditions deteriorate. As the chart below shows, the average price of the Barclays U.S. Floating-Rate Note Index has been a very tight trading range for over three years. It also highlights that during periods of market volatility, like those witnessed in 2011 during the peak of the European debt crisis, the price can still fall. And most corporate floaters are issued by financial institutions, increasing the risk of sector concentration—69% of the index is composed of bonds issued by financial institutions.4 Keep in mind that the investment-grade corporate floater market is relatively small compared with the fixed-rate corporate bond market, and can sometimes be difficult to navigate. Some exchange-traded funds (ETFs) focus solely on floaters, but it’s more difficult to screen for mutual funds that have a majority of holdings in floaters. A Schwab fixed income specialist can help you navigate the market accordingly.

Source: Barclays. Monthly data as of 5/31/2016. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Bank loans—higher yields, but delayed coupon benefit

Bank loans are a type of investment that offers floating coupon rates, but they have many distinct characteristics that differ from traditional bonds. Bank loans are private investments that are generally held by funds or large institutional investors, and generally carry sub-investment-grade ratings.5 Last, bank loans are secured, or collateralized, by a pledge of the issuer’s assets, like inventory or receivables.

Despite the secured status, bank loans still carry low credit ratings and offer higher yields to compensate for the increased risks. The coupons on bank loans are similar to investment-grade corporate floaters, in that they are made up of a reference rate plus a spread. Because bank loans carry higher credit risk, the spread tends to be much higher, resulting in higher coupons.

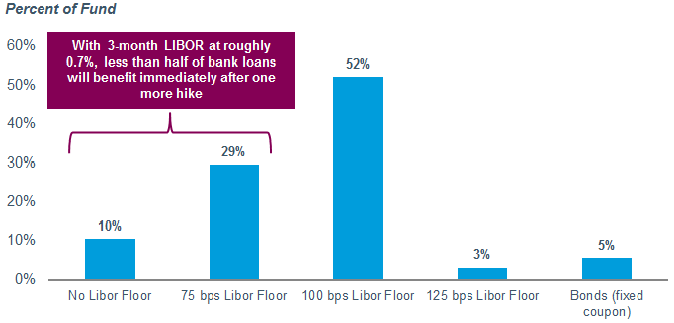

However, most bank loans these days have what’s known as a LIBOR floor. This means that regardless of how low LIBOR is, the coupon is based on that LIBOR floor. Let’s assume that a given bank loan has a coupon rate of three-month LIBOR plus 400 basis points, but with a LIBOR floor of 1%. One basis point is equal to 0.01%. While three-month LIBOR currently yields roughly 0.7%, the coupon rate would be 5%—the sum of the LIBOR floor of 1% plus the 4% spread. A majority of bank loans today have some sort of floor, meaning short-term rates would need to move up to and then above that floor before the bulk of the loan market benefits. If you’re looking to take advantage of potential higher short-term rates right away, bank loans might not be an attractive investment for that goal until the Fed hikes at least one more time. Since they are rated below investment grade and are relatively illiquid, bank loans should always be considered aggressive investments and serve as complements to a well-diversified fixed income portfolio.

One more Fed rate hike won’t benefit all bank loans

Source: Bloomberg and Powershares, as of 2/2/2016. Statistics represent the holdings of the PowerShares Senior Loan Portfolio ETF (BKLN), as constituents of bank loan indices are not available. The information provided here is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice.

Intermediate and long-term bonds not as affected

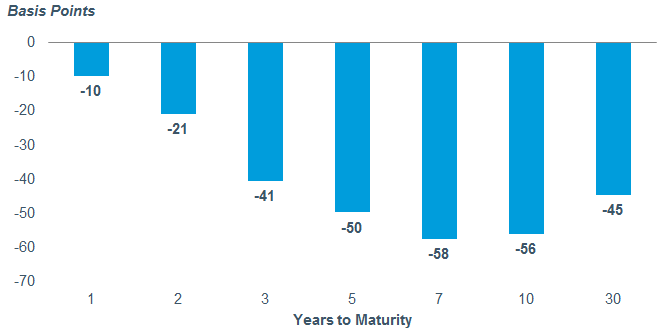

While a rise in the Fed funds rate will likely push short-term rates higher, the effect on intermediate- and long-term bonds is less concrete.

Since the December rate hike, intermediate- and long-term Treasury yields have fallen sharply

Source: Bloomberg. Yield change from 12/16/2015 through 6/6/2016. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Long-term bond yields tend to be driven more by growth and inflation expectations; today both of those remain below historical standards. And a key driver of long-term bond yields today is the level of yields of global bonds. Low global yields should help to keep demand for U.S. bonds high, and therefore mitigate a large rise in interest rates. While the Fed is in the process of raising rates, many other developed-market economies, like Japan and those in Europe, are still lowering their interest rates and enhancing their quantitative-easing programs. While 10-year Treasury yields hovering below 2% may seem low to investors, they are well above the yields of bonds from many other developed economies. In Japan, government bonds with maturities of 14 years and below offer negative yields, while German bonds with maturities of nine years and less are negative.6

The prices of long-term bonds are more sensitive to long-term interest rate fluctuations, but we don’t expect long-term rates to rise much from here, as foreign demand, as well as low growth and inflation expectations, should keep yields relatively anchored.

1 Duration is a measure of the sensitivity of the price of a bond to a change in interest rates.

2 Source: Bloomberg and Barclays. Yield change and total return from 10/14/15 through 12/29/15. Total return assumes reinvestment of coupons and capital gains.

3 Source: Barclays. Trailing 12-month total returns for the Barclays U.S. Treasury 1-3 Year Bond Index from 12/31/1992 through 5/31/2016

4 As of June 3, 2016

5 Sub-investment-grade ratings are those rated Ba1 or below by Moody’s Investors Service or BB+ or below by Standard & Poor’s.

6 Source: Bloomberg, as of 6/7/2016

Collin Martin, CFA, is director of fixed income at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.