The flood of assets into the funds has irked lawmakers, nonprofits, and even some billionaire philanthropists. They’re calling for new rules to unlock more of the almost $1.5 trillion in private foundations and DAFs—a pool of money earmarked for good causes but impossible for most nonprofits to access. “The needs have never been greater,” says Melanie Lundquist, who with her husband, California real estate developer Richard Lundquist, has committed $400 million to charity. After receiving a tax break for a donation, “I just don’t think we have the right to shelter that money.”

Defenders of the funds say their convenience stimulates more giving. Wealth advisers point out that it takes just a couple of clicks to make a gift. “DAFs are flexible, accessible giving vehicles that really democratized charitable giving,” says Elizabeth McGuigan, senior director of policy and government affairs at the Philanthropy Roundtable, a group that advocates for fewer restrictions on charitable giving. Foundations use the funds for legitimate purposes such as pooling resources and donating internationally, she says, and any changes to DAF rules could have unintended consequences. “Charities lose in the long run if there are more handcuffs on charitable giving,” she says.

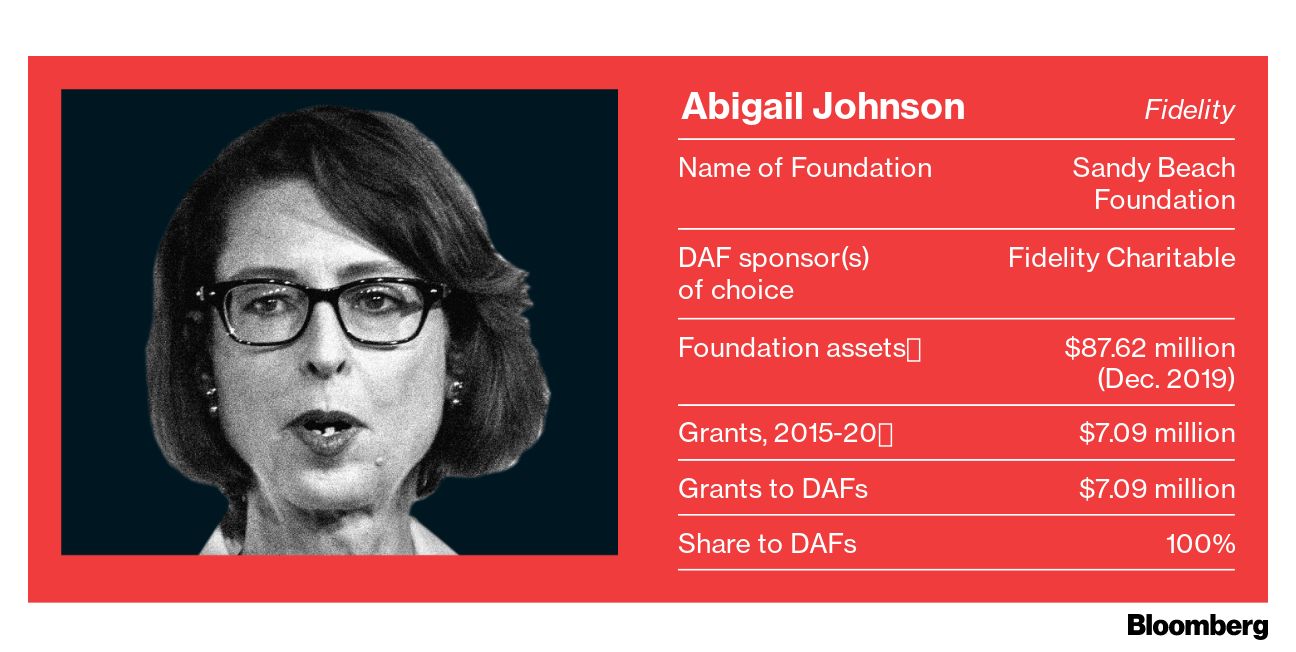

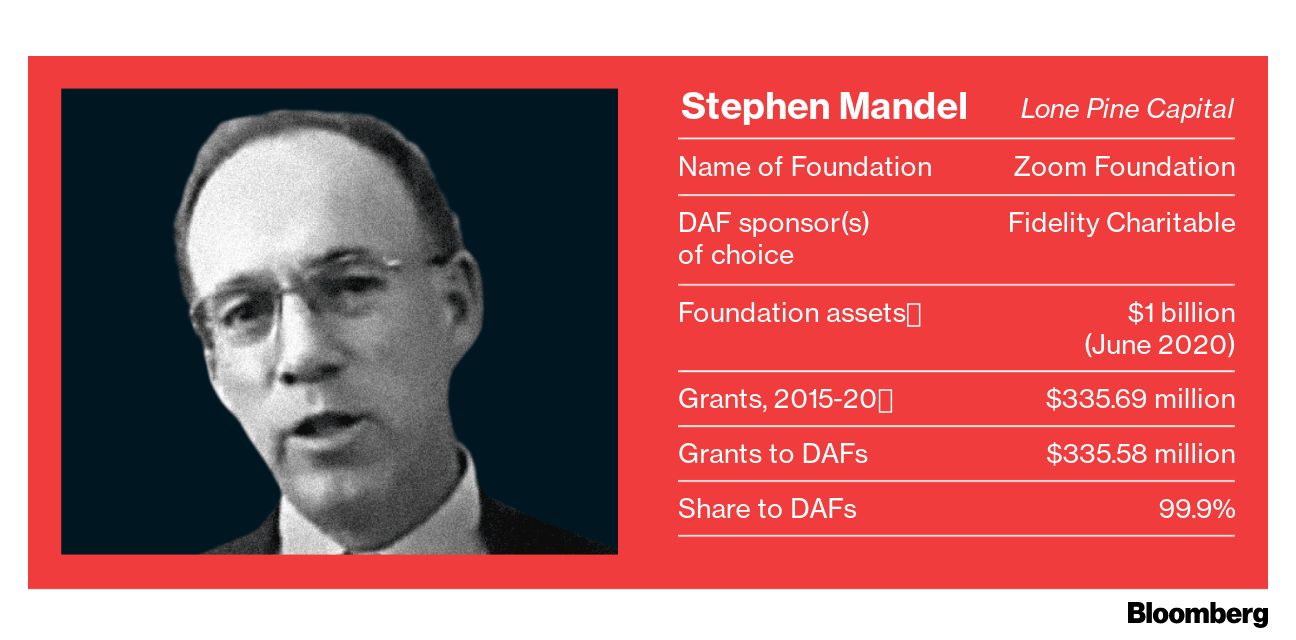

Representatives of the biggest DAF sponsors say their funds pay out more in aggregate than foundations. Fidelity Charitable says DAFs “can be efficient, low-cost, and impactful vehicles.” Schwab Charitable adds that “new regulations may unintentionally discourage giving.” And Vanguard Charitable points to its low costs, which make “even more available to charities across the country and world.”

Still, charitable giving as a share of the economy hasn’t budged in decades, despite a surge in the fortunes of the top 0.1% and promises by billionaires such as Musk to donate their wealth eventually. After an initial burst of generosity at the start of the pandemic, donations including those to DAFs failed to outpace inflation in 2021, rising 4%, to $485 billion, according to Giving USA estimates.

Meanwhile, more of those gifts are getting soaked up by DAFs rather than going directly to the needy—15% of individual giving in 2020, up from 3% in 2009. That wouldn’t be as controversial if donors merely used the funds as checking accounts to park their donations before disbursing them to charities. And some do use them that way. They include billionaire MacKenzie Scott, former wife of Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos, who’s given away money at an unusually fast pace. DAFs paid out grants of $34.7 billion in 2020, the National Philanthropic Trust estimates, but that’s $13.2 billion less than they received.

And some, such as the Allenders, are letting their funds sit entirely idle. From 2015 through 2020, the Allender Family Foundation sent a total of $3.2 million to one of Fidelity’s charitable accounts, the only grants it made each year. Patrick Allender, a former chief financial officer of conglomerate Danaher Corp., funds it, but it’s run by his son, John, who says the money is parked in the account because he doesn’t know yet what cause the family wants to champion. He offers no time frame for when the stash will ultimately make its way to charity. “I don’t know when I’m going to find that cause,” he says.

In a study of more than 2,600 DAF accounts, the Council of Michigan Foundations found that the majority of donors paid out less than 5% of assets in 2020. More than one-third gave nothing to charity at all. The biggest sponsors of the funds have rebuffed calls to release that kind of account-level data, even as the number of accounts has swelled to more than 1 million. As of 2020, DAFs held almost $160 billion, an 85% increase in four years. Although the industry says it’s paying out more than one-fifth of its assets a year in aggregate, the reality is probably less: Some of the biggest recipients of grants from the funds are other funds, as donors shift money from one sponsor to another. “There’s a lot of paralysis with this very wealthy set,” says Stephanie Ellis-Smith, chief executive officer of Phila Engaged Giving in Seattle, who advises the rich on philanthropic plans. “Oftentimes you see the more money there is [in a DAF], the slower it is to move out.”