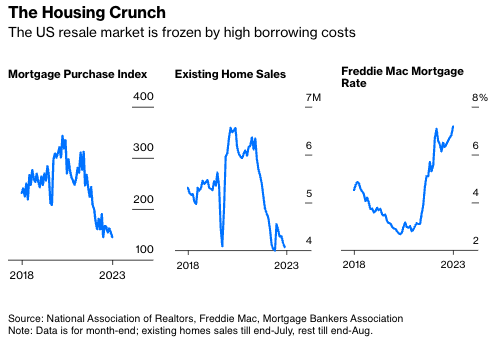

The hope for the U.S. resale housing market a year ago was that inflation would peak, interest rates would fall, and lower mortgage rates would help unfreeze the buying and selling of existing homes. That hasn't happened.

While inflation has declined, real economic growth has, if anything, accelerated. Faster growth has pushed mortgage rates to a 22-year high, sending mortgage purchase applications to their lowest level since 1995 last month.

As we’re learning, a decline in inflation isn’t enough to allow interest rates to fall if economic growth remains as hot as it’s been. That puts the resale housing market—typically seen as a cyclical part of the economy—in a spot it hasn’t been in since at least the early 2000s.

To unfreeze the market, we need borrowing costs to fall, which would allow homeowners with low mortgage rates to be able to afford to move. For interest rates to fall, economic growth needs to slow. Therefore—and it’s weird to say but appears to be true—what the resale housing market really needs is a slower economy. This is an important dynamic to consider as there are finally reasons to expect growth to slow in the first half of 2024.

Essentially, what we’re seeing is a tug-of-war between the real economy and the financial economy—at a time when unemployment is low and economic growth is strong, markets lack confidence that inflation can sustainably return to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, pushing borrowing costs higher.

Economic growth this year has been powered by a mix of supply chains healing and investments catalyzed in part by fiscal policy. Automobile production is recovering as shortages of key inputs like semiconductors ease. Construction spending on manufacturing has surged as companies take advantage of subsidies passed in the Inflation Reduction Act. Consumption growth continues to be strong.

If there’s a cost to this, it’s that the higher rates that have accompanied this growth are squeezing the financial economy. Average new car loans now have an interest rate of 9.5%. The 30-year mortgage rate approached 7.5% last week. Lenders have tightened credit, and there's been very little bank loan growth since the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March. We learned last week that existing home sales in July approached the low levels experienced during the depths of the 2008 financial crisis. They will likely fall somewhat more when contracts signed in August are reflected in the data.

Even though the decline in inflation indicates that things are not as unbalanced as they were a year ago, the squeeze on the financial economy is a different way in which the economy is out of balance. Higher loan rates are already having an impact as evidenced by a sharp decline in the Conference Board’s August gauge of consumer confidence. Further confirmation of this will help lower interest rates in the market, restoring some balance and allowing important parts of the financial economy such as the resale housing market to operate.

As the real estate brokerage Redfin Corp. noted last week, a homebuyer on a $3,000 monthly housing budget has lost $71,000 in purchasing power over the past year in large part due to the rise in mortgage rates, which applies to both first-time buyers and existing owners looking to move. The much-publicized “mortgage rate lock-in” for homeowners unwilling to give up 3% rates can also be seen as homeowners unable to afford buying a home with a mortgage rate above 7%. If they can't afford to buy, they're not going to sell, denying the resale market a transaction.

Resale transactions improving as the overall economy slows might seem counterintuitive for people who think primarily of the 2008 recession and the housing market crash playing out simultaneously. Go back a bit further to the early 2000s for a time when the resale market thrived in a slower-growth environment—existing home sales increased from just over 5 million a year to 6 million a year between 2000 and early 2003.

This doesn't mean the resale housing market needs a recession to improve, or that people whose livelihoods depend on housing transactions should root for a broad-based economic downturn. Real gross domestic product growth more in the 2% range (rather than the more than 5% projected by the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow forecast) should be enough to take some pressure off interest rates and provide relief to borrowers and homeowners looking to move. That kind of pace seems plausible in the first half of next year and would be welcome.

We don’t even need the Fed to cut the benchmark interest rate for this scenario to play out. Real GDP growth slowing to a pace of around 2% or lower would give markets confidence that policymakers are done with hiking interest rates, and that it's time to price in rate cuts. This dynamic would serve to lower mortgage rates even before the Fed officially loosens policy. We saw the reverse scenario unfold in the spring of 2022, when mortgage rates surged above 5% when the Fed had, until that point, only raised the Fed Funds rate by 0.25%.

It’s strange to be in the position of hoping economic growth slows somewhat, but the financial economy needs relief. The current level of interest rates is a pain point for many, just as elevated inflation was last year. Slower growth is the only way to bring both down.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is founder of Peachtree Creek Investments.