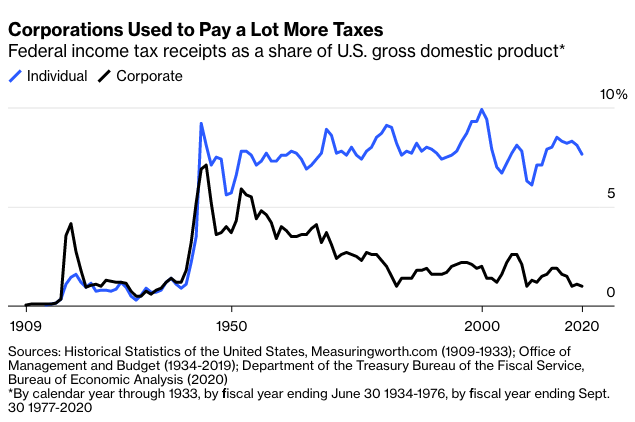

There are few policy discussions that can’t be improved with a chart that goes back more than century. So as the corporate income tax emerges as a leading focus of President Joe Biden’s plans to raise money for infrastructure and other priorities, here’s a look a how much money the tax and its precursor, the corporation excise tax, have brought in since 1909 — with individual income tax revenue alongside for comparison.

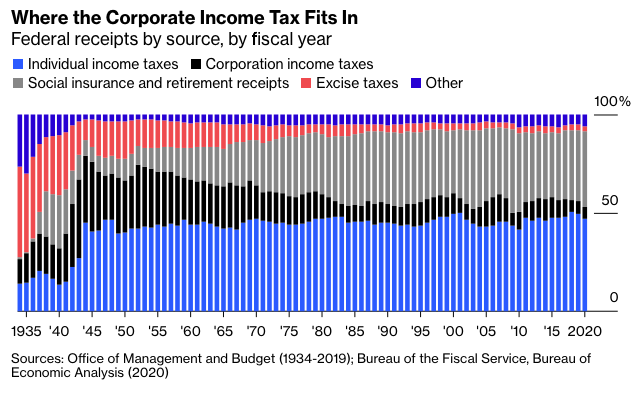

The corporate tax predated the individual income tax by four years, and during World War I it raised far more money. In the 1920s and 1930s the two brought in similar shares of federal revenue, although in those days excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco and other products sometimes brought in even more. Nowadays the corporate income tax comes in a distant third among the federal government’s revenue sources, far behind not only income taxes but social insurance taxes (Social Security and Medicare) at 6.2% of federal receipts in the fiscal year that ended in September.

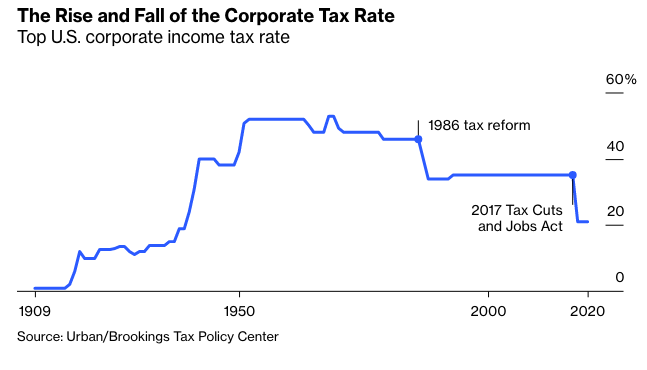

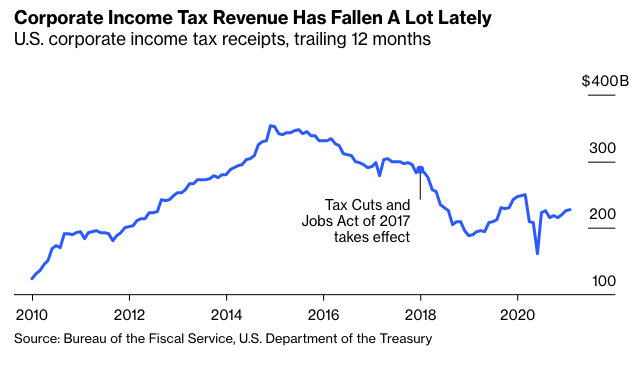

What happened to the corporate income tax? Well, one thing is that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 passed by the then-Republican-controlled House and Senate and signed into law by then-President Donald Trump slashed the top rate for corporations from 35% to 21%. The resulting dip in revenue is quite apparent in monthly tax data.

Also apparent, though, is the decline during the three years before the tax cut. That can be chalked up in large part to the business-focused “mini-recession” of 2015-2016 — corporate income tax receipts tend to be extremely cyclical — but there was also a wave of “inversions” in which U.S. corporations merged with foreign companies and shifted their headquarters overseas to avoid U.S. taxes. And as is apparent from the top two charts, declines in corporate tax revenue aren’t exactly a new thing.

To restate: It’s important not to understate the impact of Trump’s tax cut, as corporate income tax receipts fell by $91.9 billion, or 68%, in the year it took effect despite an acceleration in economic growth that year. The Joint Committee on Taxation’s final assessment before Congress approved the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act pegged the corporate rate cut as the bill’s single biggest revenue loser — at an estimated $1.35 trillion over 10 years — and subsequent evidence seems to indicate that it is reducing tax receipts by even more than expected. Yet it’s also important to acknowledge a context in which corporate income taxes had long ago ceased to be a major pillar of U.S. government finances.

In the 1950s, big U.S.-based corporations were so dominant globally and so closely identified with their home country that some executives seem to have perceived their high tax burden as something of a patriotic duty. When a senator asked General Motors Co. President Charlie Wilson during his confirmation hearing to become Secretary of Defense in 1953 if his stock ownership in and loyalty to GM might result in conflicts of interest at the Pentagon, Wilson famously replied:

I cannot conceive of one because for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country. Our contribution to the Nation is quite considerable.

In subsequent decades, GM and other big companies were battered by foreign competition at home while in some cases drawing higher profits from operations overseas. Patriotism fell out of favor as a justification for corporate decisions, differences in corporate tax rates between countries began to matter more and economic theories that emphasized the costs of taxing investment and production were ascendant. Congress began to lower the corporate tax rate, at first gingerly in the 1960s and 1970s and then with a big drop in the 1986 tax reform law (which was accompanied by a fair amount of loophole-closing).

Which bring us back to that question of what happened to the corporate income tax. The main answer seems to be that, through a mix of action and inaction, U.S. policy makers opted to stop taxing businesses so much.