No matter what our financial circumstances are, we all have to assess what we have and prioritize our goals. Start with the numbers: Tell clients to think through what they have and what they want, and build around that. Clients need to have an honest conversation with their financial advisor, who is experienced in projecting the costs of the things they want to do and can help them understand the trade-offs necessary to enforce their priorities.

Everybody should be evaluating the impact of their spending, no matter their income level or wealth. List all their priorities: “I want to remain financially independent.” “I want to take one nice vacation a year.” “I want to be able to help my child with her rent if she needs it.”

And if you can’t afford to do all the things you want, which ones are the most important? When it comes down to it, helping family tends to take priority over lots of other things. In most cases, parents and kids ultimately want the same things, and they just have to agree on how to get there.

One of my clients, “Ruth,” had been giving her daughter, “Heidi,” sums of money whenever Heidi expressed a need or a desire. Ruth was essentially handing a blank check over to her child with alarming regularity. But when I spoke to Heidi, with Ruth’s permission, of course, they were able to get on the same page.

I asked Heidi if she would like her mom to move in with her when Ruth had depleted her assets and was forced to sell her home. That put a new spin on the discussion. Heidi was truly unaware that her mom’s financial well-being was endangered by the money she was giving so freely. Since Ruth’s husband had passed away, her income was greatly reduced. She received only a fraction of the Social Security and pension income they’d been getting as a couple. Ruth would be fine—as long as she didn’t give all her assets away.

We all wanted the same thing: for Ruth to be happy and do well and not end up living with Heidi. We were able to agree on a small amount that Ruth could afford to give her daughter each year, given her financial picture, and that worked out very well.

Other scenarios haven’t ended as well, mainly because a child occasionally believes that his priorities are most important. If clients have a child who is adamant and the parent gives in, particularly if that parent is widowed and there is no other source of moral support when it comes to these tough decisions, then the parent may well choose to drain assets attempting to placate the child.

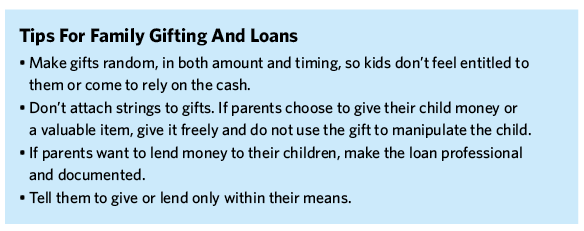

One strategy we have used for scenarios in which kids are coming and asking for money on an as-needed (or wanted) basis is creating trust accounts for the kids. The parents are then able to tell the children, “This is all you get. The trust will distribute a set amount each year, but you can’t come back and ask for more.” Sometimes the kid tries anyway, but our clients are able to say no and remind the children what was agreed upon.

We’ve also written loans from parents to children, formalizing the arrangement that way. A loan instrument in black and white, outlining the expectation of repayment, including invoices that are sent like bills, can be a powerful motivator preventing the child from asking irresponsibly for more money.

If the child should fail to repay, the loan is part of the estate, which can lessen tensions with other siblings. Trust me, the other kids in the family are generally not happy when one sibling is asking for and receiving large amounts of cash from Mom and Dad. A loan agreement can reduce the financial impact on the other children and take away some of the animosity that may result when parents gift a substantial amount of money to a child.