For investors contemplating retirement, chances are one of the biggest questions is how much money they can afford to pull out of their retirement nest eggs each year. The key is sustainability: what withdrawal rate will avoid exhausting savings while an investor is still alive. Financial planners call this challenge longevity risk, and it’s a growing problem since people, on average, are living longer and facing the potential for longer periods of retirement. In this article, we will discuss withdrawal rates, along with the related issue of how to generate the annual income an individual needs, distinguishing between the need for cash from the need for yield.

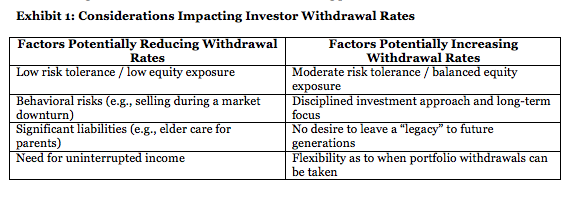

There are a number of core variables, many of which are not directly financial, which influence an appropriate withdrawal rate; obviously someone who is 65 years old may have a different outlook on his or her longevity risk versus someone who is 85. While every individual investor faces a unique personal situation complicated by health and other issues, translating these issues into a broad understanding of how they may impact an individual’s retirement can be a critical first step (see Exhibit 1). While determining a withdrawal rate is not an exact science, we thought it would be helpful to apply some numbers to a scenario based on a balanced portfolio to try to determine what a reasonable figure would be for investors to use as a starting point.

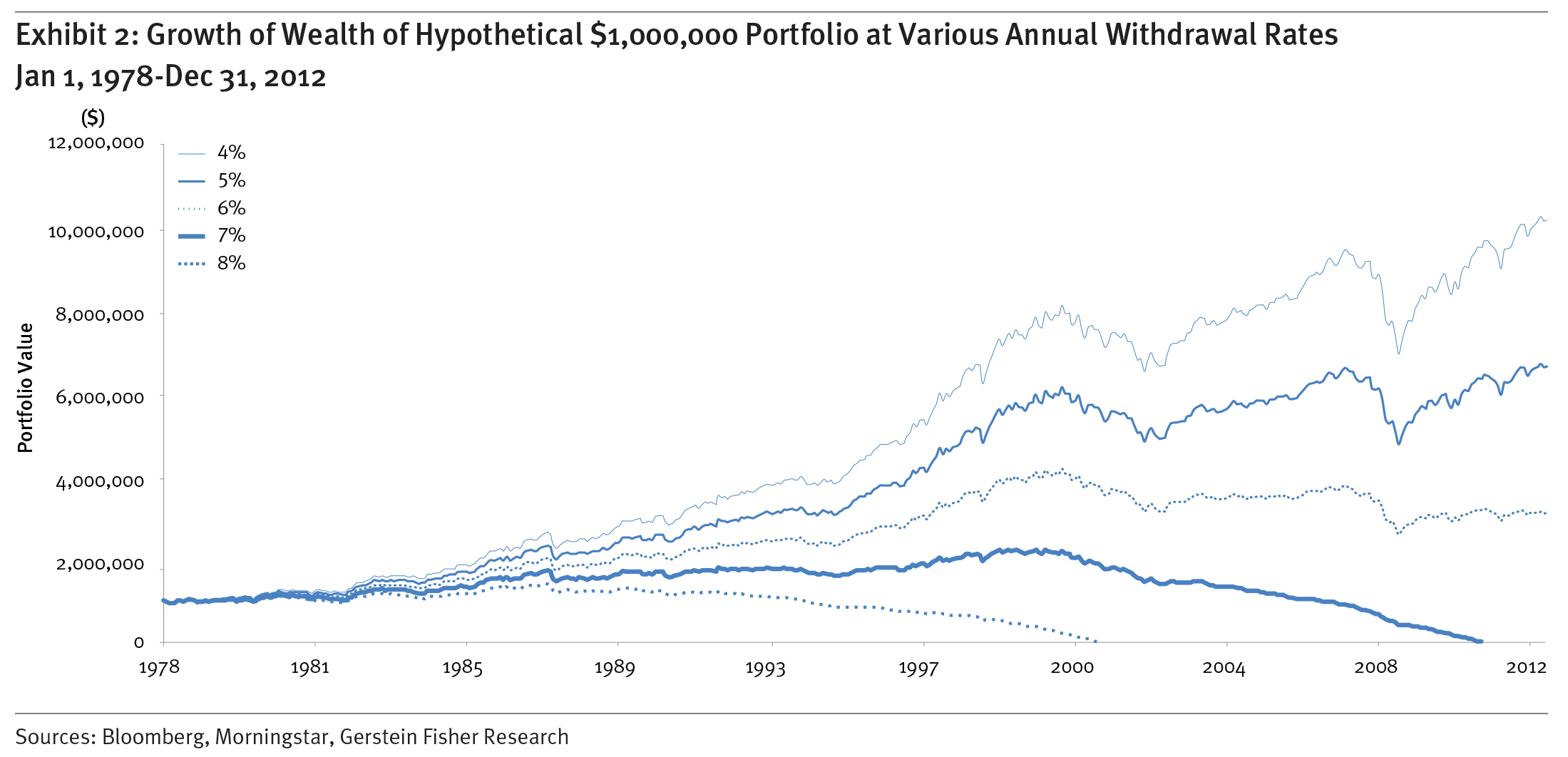

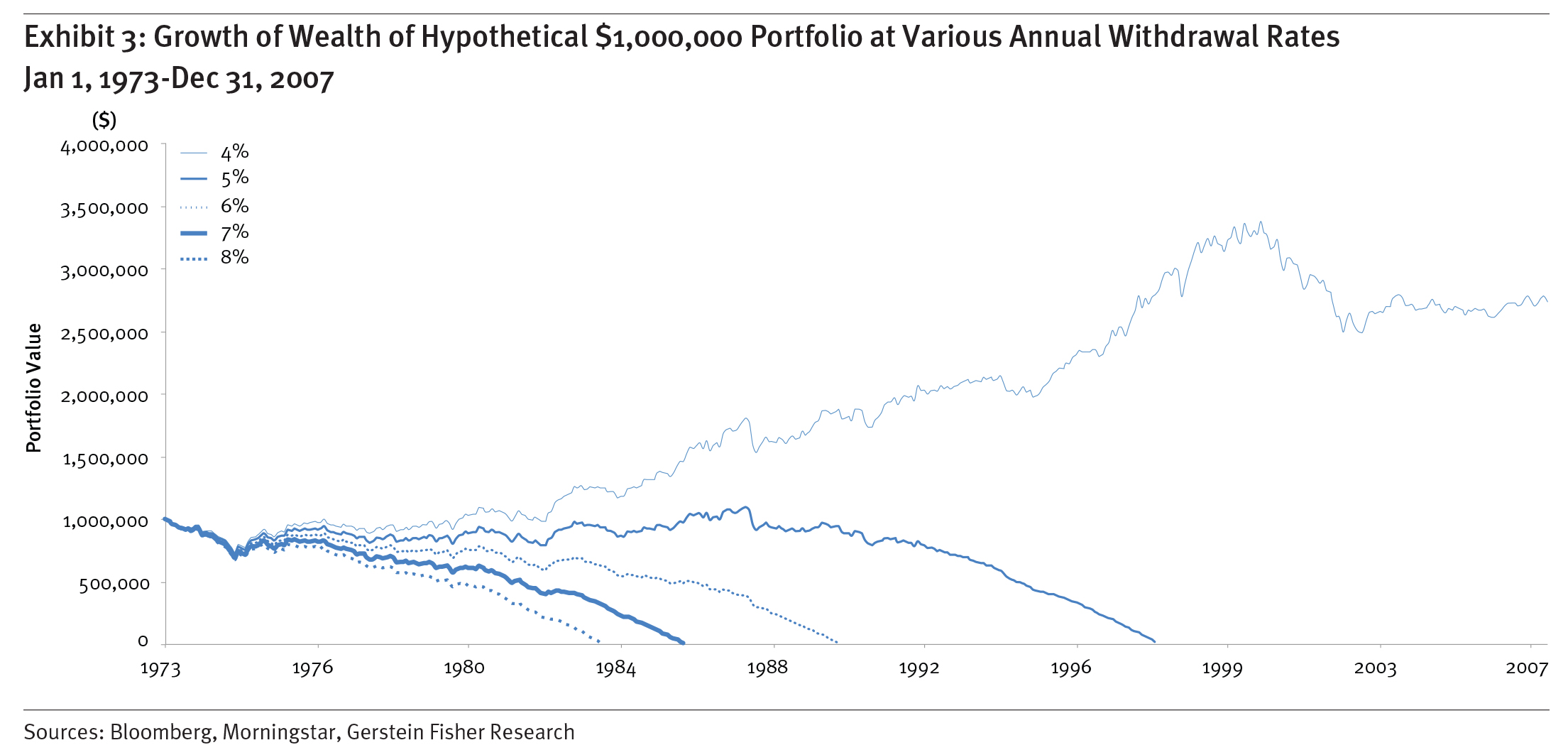

It’s also important to note that in estimating the amount of income needed from a portfolio, investors should calculate what they need after accounting for other income sources, such as Social Security, pensions and annuities. For the sake of illustration, however, we simulated a hypothetical investor’s experience under different withdrawal rate scenarios, using a 50/40/10 portfolio -- 50 percent of the portfolio invested in domestic stocks (as represented by the S&P 500 index), 40 percent in intermediate-term U.S. bonds, and 10 percent cash reserves -- as an approximation of a basic balanced portfolio.

We made the following assumptions for our study:

• The investor retires with $1 million in his portfolio and expects the portfolio to fund his living expenses for 35 years (in combination with what he is receiving from other sources).

In Exhibit 3, we evaluate our earliest 35-year time period, between 1973 and 2007 and five calendar years earlier than the earlier example. Over this investment horizon, because of generally lower investment returns, particularly in the earliest years of the scenario, we observe that only the 4 percent withdrawal rate can avoid depleting the portfolio. Even at 5 percent, less than $850 per month more initially, the portfolio would have been exhausted by January 1998.

In fact, for all six periods we studied, the 4 percent rate was the only withdrawal rate at which none of the portfolios was depleted by the end of the investor’s 35-year time horizon. This finding is consistent with academic research on the topic of withdrawal rates, including that of William Bengen in 1994 and what is commonly called the “trinity study” of Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard and Daniel T. Walz in 1998, each of which also arrived at a sustainable 4 percent rate for an investor with a “moderate” allocation.

As noted earlier, there is no magic number that is right for everyone. Depending on factors like portfolio size, lifestyle and spending requirements, age and health considerations, sustainable withdrawal rates can range from 3 percent of a portfolio or less (for conservative investors with long time horizons) to 8 percent -- all with a high probability of not exhausting assets during the specified time horizons.

• The investor withdraws a percentage of the initial portfolio (in this case $1 million) every year, with withdrawals taken at the end of each month. To simulate a 4 percent withdrawal rate, for example, in the first year, $40,000 is taken out in monthly withdrawals of $3,333 ($40,000/12 = $3,333). These monthly withdrawals are then adjusted at the start of every year based upon the actual rate of annual inflation for the preceding 12 months.

• We consider six 35-year time periods ending in each of the past six years: 1973-2007, 1974-2008, 1975-2009, 1976- 2010, 1977-2011 and 1978-2012.

• Withdrawal rates range from 4 percent to 8 percent.

• The portfolio is assumed to be in a tax-free retirement account; taxes are not considered in our analysis.

The most recent time period examined (Exhibit 2) shows the $1 million portfolio on January 1, 1978, and its value over the next 35 years, ending in December 31, 2012. Each of the five lines in the graph represents the growth of portfolio wealth at the different withdrawal rates we analyzed (4 percent to 8 percent). In this time period, from 1978 to 2012, the investor’s portfolio would have survived at withdrawal rates of 4 percent, 5 percent and 6 percent of the initial value, adjusted for inflation, and even a 7 percent rate of withdrawal avoided depleting the portfolio for over 30 of the 35 years looked at.