President Donald Trump made what seemed like a bold proposal in the latest iteration of his tax plan: To help pay for deep rate cuts, he would do away with most of the deductions that millions of Americans claim every year. On closer examination, though, that pledge looks a lot less impressive.

In principle, scrapping various deductions and loopholes is a great idea. They cost hundreds of billions of dollars, complicate the tax code, often create perverse incentives, and tend to benefit the wealthy. Any responsible reform would have to address them in some way.

One crucial question, though, is whether the tax breaks that Trump targets will generate enough savings to cover the cost -- estimated at more than $6 trillion over 10 years -- of what he wants to do, which is slash rates to 35 percent for top individual earners and 15 percent for corporations and pass-through businesses. If they don't yield enough savings, his plan will boost budget deficits in a way that economists doubt would be offset by faster growth.

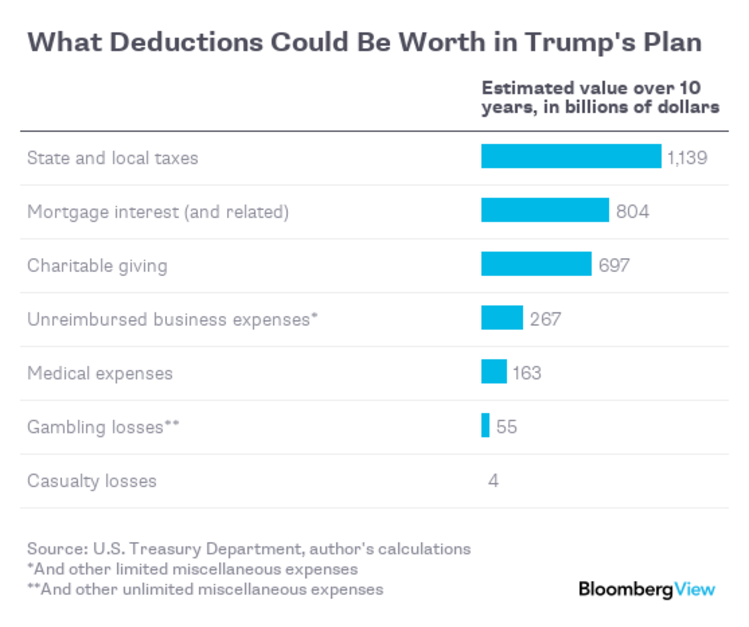

So what is he targeting, and how much is it worth? Given the lack of detail, any answer inevitably involves some guesswork. For the first part of this analysis, let’s assume that when Trump's advisers say "tax breaks," they mean the itemized deductions that people claim on their returns (we're in good company here).

Here's a very rough estimate of the value of those deductions over the next decade, in a world where rates are already at Trump's desired level:

One conclusion is that Trump is leaving a lot on the table. Although his plan claims to eliminate "tax breaks that mainly benefit the wealthy," it protects two of the biggest: The deductions for mortgage interest and charitable giving. Together, based on these estimates, they would cost $1.5 trillion over the 10-year period.

One item Trump officials have singled out is the deduction for state and local taxes -- which could save $1.1 trillion. Killing all the others, including unreimbursed business expenses, medical expenses and gambling losses, would increase that only to $1.6 trillion.

Even if Trump changed his mind and went after all itemized deductions, he'd fall short -- and not just because they don’t add up to anything near $6 trillion. Most viable proposals aimed at the mortgage-interest deduction, for example, would modify rather than eliminate it. One such idea -- replacing the deduction with a credit worth 15 percent of interest payments, limited to loans of $500,000 or less -- would save about $100 billion over the first 10 years.

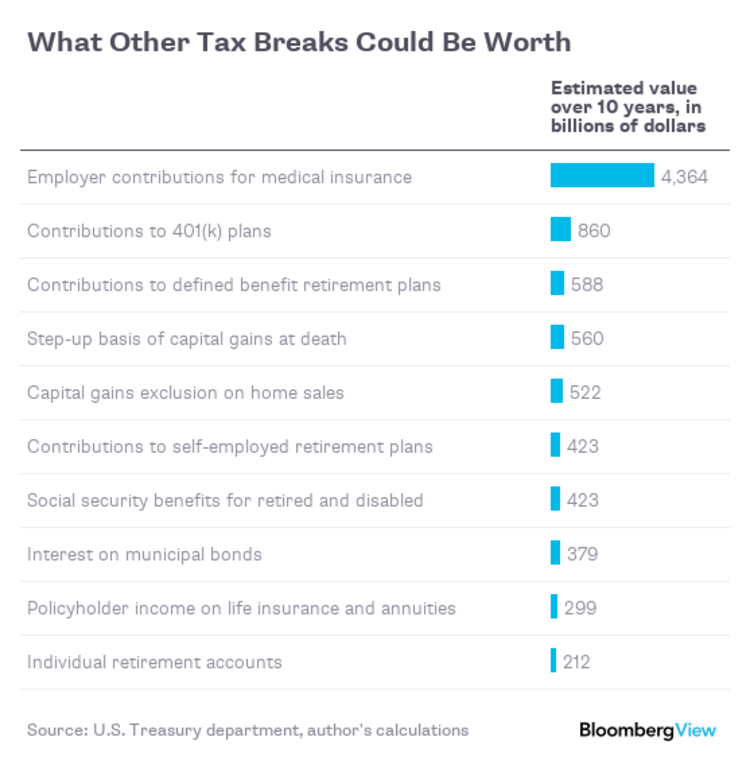

For bigger savings, Trump would have to venture into the politically fraught territory of so-called above-the-line tax breaks, the various benefits that get excluded from income before anyone starts itemizing deductions. These include employer-provided health insurance, contributions to retirement savings accounts and the "step-up basis," which zeroes out capital gains at death.

Here's an estimate -- again, very rough -- of what some of the largest could be worth over a decade: