Stock market bears have given up. That shouldn’t be a surprise after the S&P 500 has closed at yet another all-time high. Its current run without a pullback of even as much as 2% now stretches to five months. But the details of just how they came to throw in the towel, and what they now expect, are a little surprising.

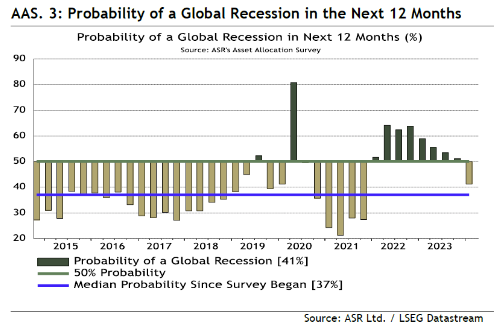

The key economic call is that a recession within the next 12 months is no longer viewed as a certainty. This week saw the latest edition of Absolute Strategy Research’s Asset Allocators survey, which polls 225 managers responsible for $8 trillion. in the last three months, they’ve slashed the odds of a recession. For the first time in two years, the allocators, who are asked to affix a probability to certain outcomes, put the chances of recession below 50%.

This is roughly in line with the findings of Bank of America Corp.’s monthly global fund manager survey. It posed the same question slightly differently, and produced much the same result. Some two-thirds of its respondents now say that a recession is unlikely in the next 12 months. Entering last year, they had regarded this as a virtual certainty:

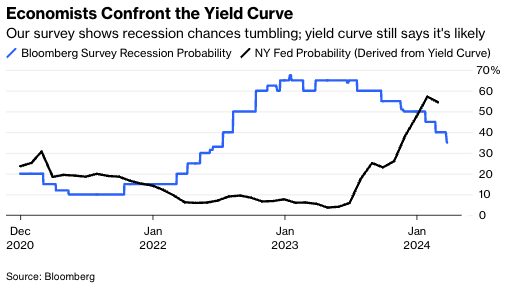

Another way to look at the recession odds comes from surveying economists. Yet another way involves gauging the implicit odds of an economic slowdown in the bond market. As the yield curve remains very inverted, meaning longer-term bonds yield less than short-term ones, it’s still braced for a recession. The New York Fed regularly publishes the implied recession probability resulting from its analysis of the yield curve. At present, it appears the bond market still thinks there’s a recession coming, while only about a third of economists agree. The number has come down sharply:

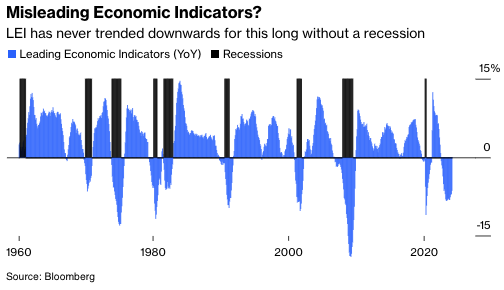

To be clear, if we really are out of the economic woods, and the US can get through this cycle without a recession — that’s amazing. There is a reason why money managers, economists and bond dealers were convinced a slowdown was coming. One of the clearest ways to demonstrate this is with the Conference Board’s leading economic indicators. Generally, when the LEI go negative year-on-year, and stay that way for any length of time, there will be a recession. Like the yield curve, this was a trusty recession indicator and suggested that one was inevitable:

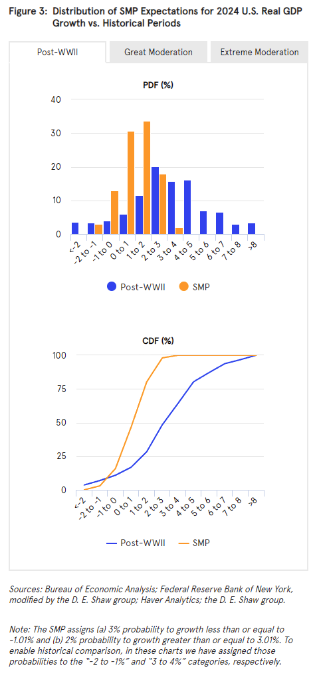

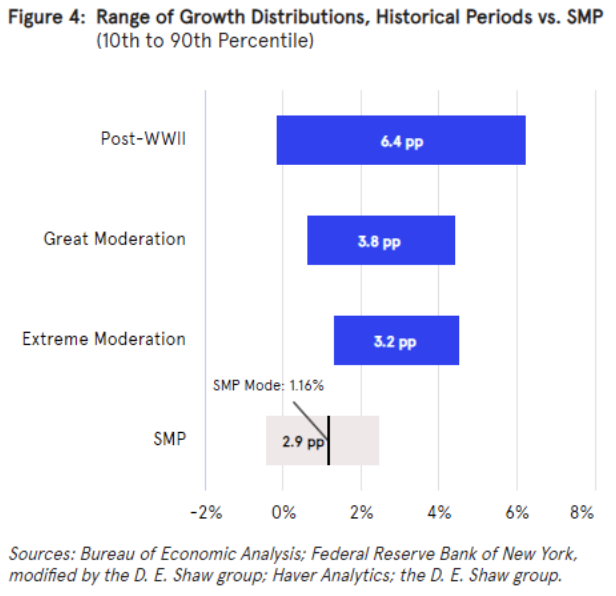

So the newfound confidence looks a tad overdone. More evidence for this comes in a fascinating paper from the hedge fund group DE Shaw, which compares estimates for growth and inflation reported by economists for the New York Fed’s regular survey known as the SMP (Survey of Market Participants). The latest growth projections are shown in the orange bars; the total spread of outcomes over the postwar period is in blue. Experience suggests outliers are more likely than economists now think:

Over the entire period, there has been a spread of 6.4 percentage points in outcomes. This has reduced to 3.2 percentage points during the “extreme moderation” since the Global Financial Crisis. The latest projections are narrower still, and suggest much less possibility for an upside surprise than history might prepare us:

DE Shaw suggests that “no landing” — a much stronger growth than now assumed — is more likely than economists think:

In our view, it strains credulity that the range of plausible outcomes for the coming year is substantially narrower than the distribution of realized outcomes during the Extreme Moderation, arguably the most stable period known to US economic history. This is especially true given the tendency for macroeconomic volatility to “cluster” over time.

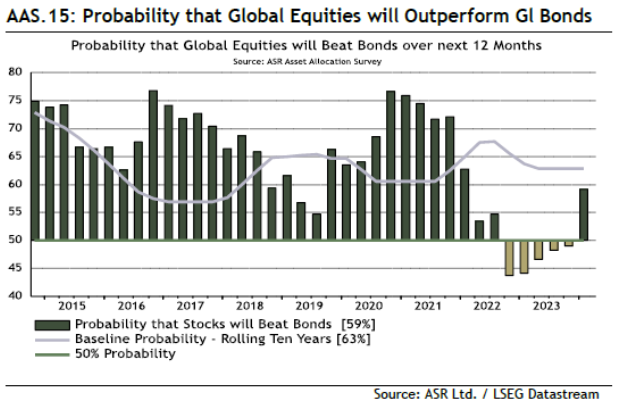

As it is, the asset allocators have enough conviction to bet that equities will beat bonds over the next 12 months. That’s a turnaround after five consecutive quarters when bonds were (incorrectly) expected to outperform. Rate cuts to combat a slowdown would generally ensure a good performance for bonds while equities suffered; so this would be consistent with a belief in “higher for longer” thanks to economic strength:

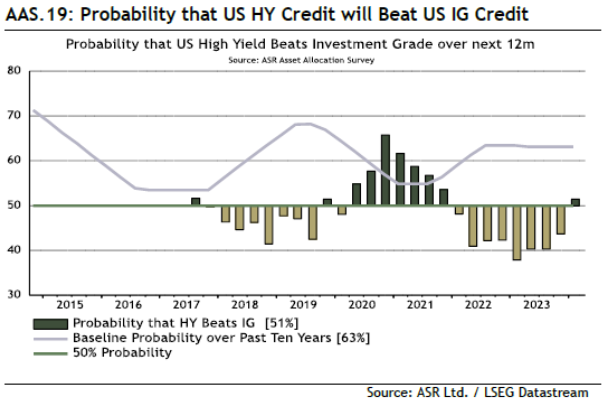

Against that, the asset allocators also now think that high-yield, riskier credit should beat investment-grade over the next 12 months. That implies optimism about the economy, but also suggests that they’ve abandoned long-held concerns for the viability of smaller companies who will need to renegotiate debt taken out on exceptionally generous terms in 2020 and 2021:

Even though investors now expect a soft landing (a slowdown in growth that requires interest rate cuts), they seem positioned for something stronger. One classic way to measure this is the relative performance of emerging and developed markets. Generally, the emerging world is much more geared to the economic cycle. That signal is diluted now by the divergence between the two economic superpowers, but if we exclude the US and China, the developed and emerging worlds have been trading in line with each other for the better part of a year. A pickup for emerging markets, at least outside China, looks overdue if no landing is in prospect:

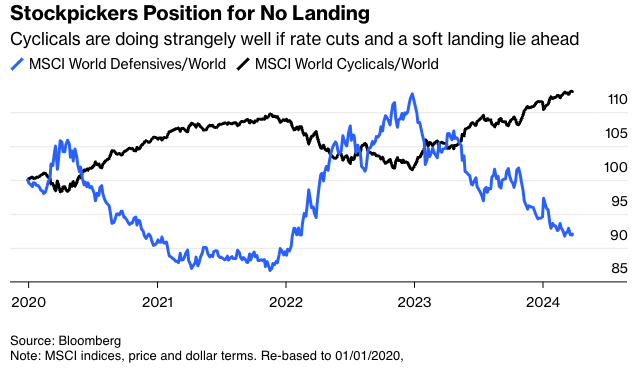

If we compare MSCI’s indexes of cyclical and defensive stocks within the developed world, however, cyclicals are surging in a way that only makes sense with the kind of growth that rules out any need for cuts:

Add all this up, and it’s easy to explain the rally of the last few months, but quite concerning that this has joined with a persisting belief that rates are heading down. The latest “Easter egg” was delivered after the close Wednesday as Fed governor Christopher Waller strongly talked down the prospects of imminent rate cuts, saying the central bank was in “no rush.” Recent inflation data had been disappointing, and “at least two months” of improved numbers would be necessary before cuts could begin. In the terms of the current market debate, that suggests he’s inching toward a “no landing” prediction. Much of the market is there already, but as we’ve seen, not all prices are yet consistent with it.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator at the Financial Times, he is author of The Fearful Rise of Markets.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.