"The Fed doesn't have a clue!" - I allege that not only because the Fed appears to admit as much (more on that in a bit), but also because my own analysis leads to no other conclusion. With Fed communication in what we believe is disarray, we expect the market to continue to cascade lower - think what happened in 2000. What are investors to do, and when will we reach bottom?

To understand what's unfolding we need to understand how the Fed is looking at the markets, and how the markets are looking at the Fed.

The Fed and the Markets

In our analysis, policies at the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) are driven by what the Fed Chair deems most important. At the risk of oversimplification, and to zoom in on what I believe is relevant in the context of this discussion, former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan put a heavy emphasis on the 'wealth effect;' in many speeches, both during and after his tenure at the Fed, he indicated that rising asset prices would be beneficial to investment and economic growth. His successor Ben Bernanke went as far as mentioning in FOMC Minutes rising equity prices as a beneficial side effect of quantitative easing (QE). Bernanke's framework, though, was indirect: he considered himself a student of the Great Depression, arguing that monetary accommodation shouldn't be removed too early when faced with a credit bust, as doing so might unleash deflationary forces once again. QE, of course, 'printed money' to buy Treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), i.e. intentionally sought to increase their prices (I take the liberty to call QE the printing of money because, amongst others, Bernanke himself has referred to QE as such; no physical money is printed, but it's created 'out of thin air' through accounting entries at the Fed).

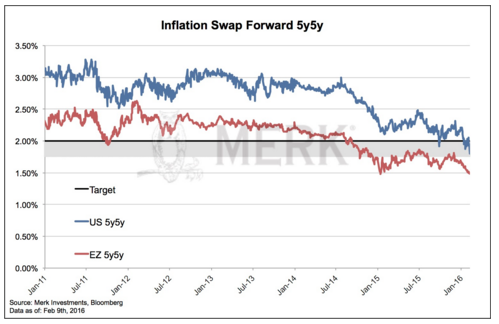

This prelude is necessary to understand Janet Yellen, a labor economist. I am not aware of labor economists focusing on equity prices. Neither am I aware that labor economists use forward inflation expectations as a gauge to predict labor markets. Sure enough, any FOMC member is likely to look at various indicators of inflation in the course of their job, but for a labor economist, it may merely be yet another data point. The reason I say this is because, during Bernanke's tenure, when inflation expectations dipped towards the 2% threshold, he would talk about the need for QE (the chart shows a measure of longer term inflation expectations):

In contrast, Janet Yellen has been rather quiet about the chart, instead pointing to other surveys that show long term inflation expectations remain well anchored. Interestingly, Mr. Draghi at the European Central Bank (ECB) looks at a similar chart of the Eurozone inflation expectations and rings the alarm bell, suggesting policy action may be needed to get those inflation expectations higher once again.

A labor economist is, in my assessment, destined to look at stale data, as jobs data tend to be backward looking. With what I believe is a 'backward looking' framework, the Fed may well be clueless: in their latest FOMC statement, the Fed removed their view that risks are balanced in favor of saying that the balance to risks needs further assessment. That is, I allege the Fed no longer has a view of where we are in the economy; it looks like I am not the only one with that interpretation, even Vice Chair Stan Fischer has indicated they need to wait for more incoming data to assess the economy. It's one of the reasons the Fed may look ever more like a huge ocean tanker that's slow to move. The fact that the Fed may be slow to move and not be quite as activist is not a bad thing per se, but needs to be understood in the context of how the markets will behave.

The Markets and the Fed

Let's look at the flip side: the market. For years, asset prices were rising on the backdrop of low volatility. That low volatility was, in my assessment, induced by highly accommodative monetary policy. I like to refer to it as an era of 'compressed risk premia.' In that environment, I allege investors got over-exposed to risky assets; that's a rational reaction to a world that is perceived to be less risky. But, of course, I would argue the world is still a risky place; it's only that the risk has been suppressed. As such, whenever the Fed started to contemplate an exit, I would say the market threw a 'taper tantrum,' then, last August, the Fed suggested it really meant business, although it got cold feet yet again, at least for a few weeks. It was too late, though: I visualize it as the Fed opening the lid to the pressure cooker it had left on the hot plate for too long.

As a result, investors may be waking up to the notion that markets are risky after all and that they must sell risky assets (equities, junk bonds, amongst others) to rebalance their portfolios. As a result, investors may be increasingly interested in capital preservation, i.e. 'sell the rallies' rather than 'buy the dips.'

The Yellen Fed, looking at this, may shrug it off for two reasons: first, they may realize they made a mistake when they caved in to the markets, postponing the September rate hike. After all, if they blink because of a hiccup in the markets, they become slaves to the markets. That's a fair point, but in my opinion, the reason the Fed is a slave of the markets is because they've made themselves a slave of the markets with their emphasis on 'data dependency.' It's not that relying on data is a bad idea per se, but if the Fed is not clear on how it interprets what, with the only certainty that there's a heavy emphasis on backward looking employment data, one does not need to be surprised that the market is imposing its own views on the Fed rather than the other way around.