Reviewing a century of U.S. data, a recent study finds a strong positive correlation between the level of volatility in the nation's gross domestic product (GDP) and the stock market's dividend yield. The connection suggests that shifts in the general level of macroeconomic risk-a regime change-is a factor, perhaps the dominant factor, for changes in the equity risk premium over medium- and long-run horizons. One of the empirical clues: Lower dividend yields tend to coincide with lower economic volatility, and vice versa, according to "The Declining Equity Premium: What Role Does Macroeconomic Risk Play?" (by Martin Lettau, et al, in the Review of Financial Studies, July 2008).

By that standard, the relatively modest level of macro risk over the two decades before 2008-the "Great Moderation"-may explain why the realized equity risk premium for the past decade is unusually low. For the ten years through February 2011, the U.S. stock market's excess return was just over 1% annualized (the total return on the Russell 3000 less three-month Treasury bills). That's far below the long-run average of nearly 6% since 1926, according to Ibbotson Associates.

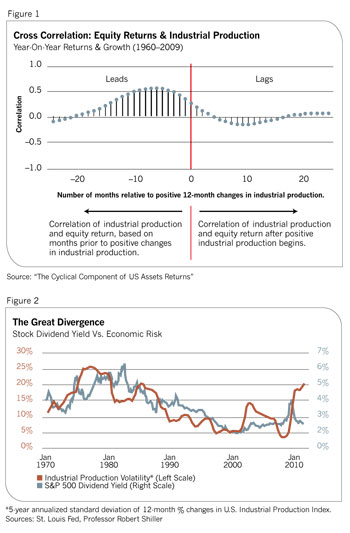

Does the recent return of sharply higher economic risk imply higher equity returns for the long-run future? Volatility has increased recently, thanks to the Great Recession and the financial crisis of 2008. Using industrial production as a proxy for economic activity shows that macro risk has recently jumped to heights unseen in nearly 20 years.

Why should higher economic volatility be associated with higher expected returns? One explanation: Investors demand additional compensation for enduring more risk. Modern finance theory assumes as much, and there's no shortage of supporting empirical studies. Consider the evidence that economic volatility tends to drive stock market volatility, a relationship found throughout foreign markets, according to "Measuring Financial Asset Return and Volatility Spillovers, With Application to Global Equity Markets" (Francis X. Diebold and Kamil Yilmaz, The Economic Journal, January 2009).

Estimating how the market prices risk in real time is tricky, of course. Among the useful clues is the dividend yield, which boasts a productive history for discounting expected equity returns. That inspires comparing the market yield to economic risk. The relationship is far from perfect, as Figure 2 reminds us. Yet it's also clear that the fall in macro volatility over the years has been accompanied by a lesser dividend yield.

More recently, economic risk and yield have risen sharply. But while macro volatility is still high, the dividend yield has recently tumbled ... again, thanks to sharp gains in stocks since the last recession ended. Will the divergence narrow? If so, under what conditions? Is the recent jump in economic risk a temporary affair that will soon give way to a revival of the Great Moderation? Or will the dividend yield rise (i.e., stock prices fall) in sympathy with a new era of elevated macro risk? It's too soon to say for sure, although the relationship bears watching.

The Problem Is Us

Looking for signals from the evolving relationship between macro and markets isn't easy, but it can be helpful when used with other tools for estimating return and risk. For all the econometric studies to draw on, however, a certain amount of finesse is needed to soften the hard fact that turning points in the business cycle are easier to see after the fact. No wonder that NBER typically waits a year or more to retroactively call peaks and troughs. Finding real-time clues is a challenge, but not necessarily hopeless.

Once again, the financial literature suggests lots of intriguing possibilities. Electricity usage, for instance, is considered a valuable proxy for monitoring the business cycle in real time. It's a practical idea because, a) electricity consumption/generation data is available monthly with minimal lag; and b) electricity can't be stored, which makes it a useful benchmark of real-time demand for economic activity. Accordingly, history suggests that electricity can shed light on expected risk premiums ("Electricity Consumption and Asset Prices," a working paper by Zhi Da and Hayong Yun).

Dissecting the finer points of macro and markets is helpful, but it doesn't automatically make exploiting the apparent opportunities any easier. "One of the hard facts for all of us to chew on is that when prices are low relative to book value, dividends, earnings, etc. doesn't seem to indicate that future earnings are going to be bad," notes Chicago University's Cochrane. "That seems to indicate a buying opportunity: a time when returns are going to be higher."